Milky Way: Icy observatory reveals 'ghost particles'

- Published

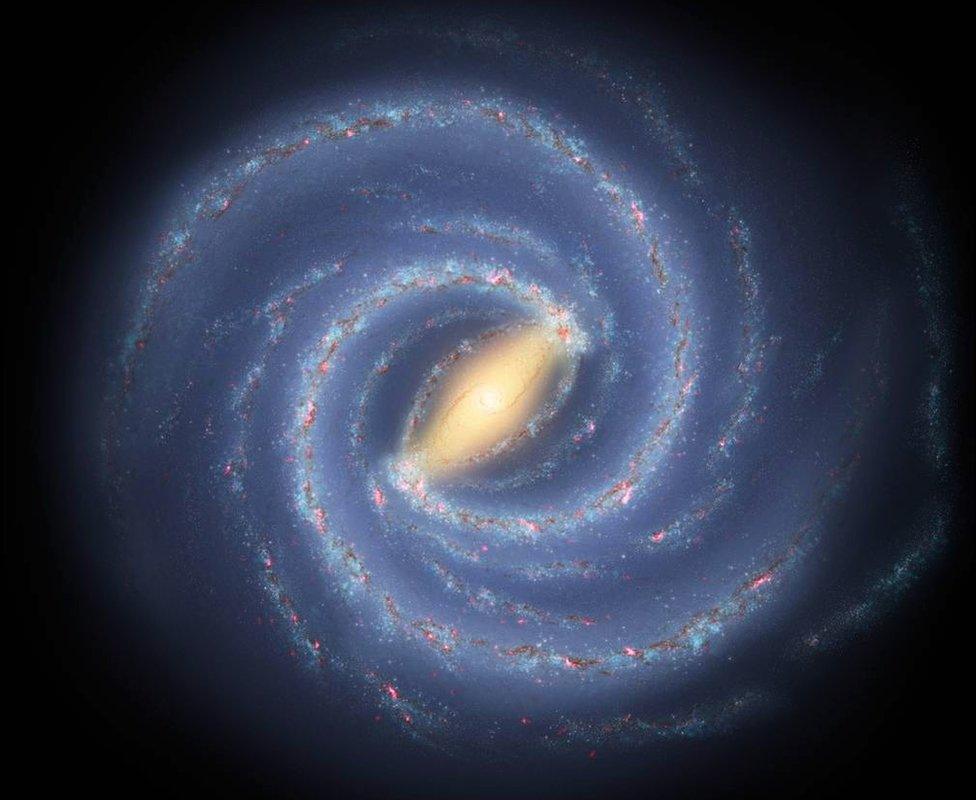

The image shows our Galaxy, the Milky Way, in ghostly particles called neutrinos

An astronomical detector buried in Antarctic ice has provided a view of our Galaxy that has never been seen before.

The blurry, extraordinary image is of the Milky Way, but it is composed of the "ghostly" particles that are emitted by the reactions that power stars.

The particles are neutrinos, which are extremely difficult to detect on Earth.

To find them, scientists turned a vast block of Antarctic ice into a detector.

"This is the first time we're seeing our Galaxy using particles rather than photons [of light]," Prof Subir Sarkar from the University of Oxford told BBC News. This, he explained, provides a view of "high energy processes that shape our Galaxy".

Neutrinos can be thought of as astronomical messengers that point to those fundamental processes. They are created when particles called cosmic rays - that are rattling around at near light speed - smash into other matter.

Capturing those collisions basically means capturing neutrinos. And that is not easy.

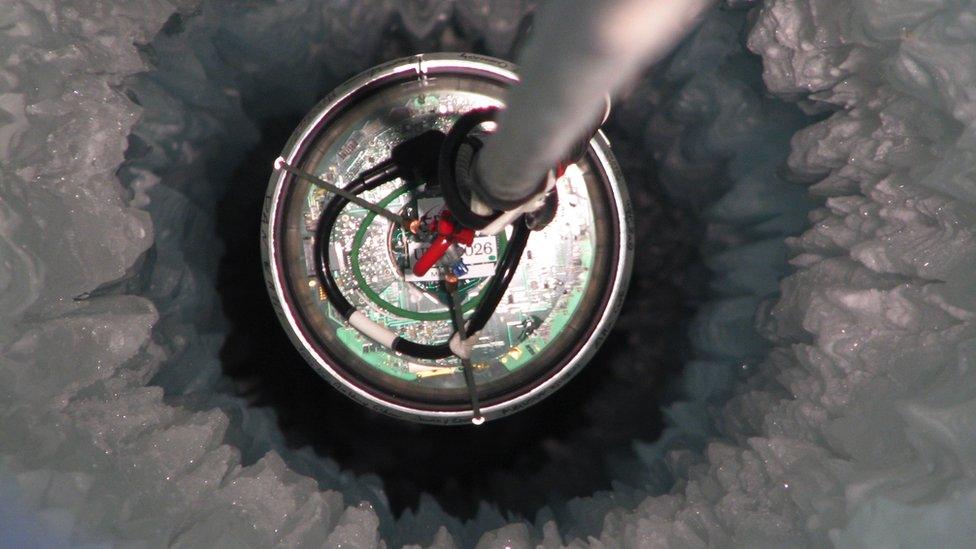

Thousands of individual neutrino detectors are suspended in the ice on cables

"The neutrino is a ghostly particle; it's basically almost without mass," explained Prof Sarkar. "They're essentially moving at the speed of light and might pass through the Galaxy and not interact with anything. That is why, in order to see them, you need a massive detector."

The detector that scientists and engineers designed is called IceCube, external. It is composed of thousands of sensors on long cables that are drilled and frozen into a 1km cubic block of ice. The whole array is buried close to the South Pole.

Whenever a neutrino interacts with one of the billions of ice molecules, that interaction is captured.

"Essentially, by knowing which sensor is triggered and at what time, we can reconstruct the direction [that neutrino came from]."

The scientists say the discovery, published in the journal Science, external, is an entirely new window on our Galaxy.

Mapping the Milky Way

An artist's concept of our Galaxy, created using astronomical data

It is a century since astronomer Edwin Hubble, external discovered that the Milky Way was just one of millions of galaxies - that it was our place in a vast Universe.

Prof Naoko Kurahashi Neilson, a physicist at Drexel University in Philadelphia, and another member of the IceCube team, said that humans had been studying it for millennia. "We've seen it in many wavelengths of light - like radio waves and gamma rays - but since the dawn of time it was always in electromagnetic radiation. In all wavelengths of light or photons."

"This is the first 'map' of our Galaxy in something [other than light], and it's in high-energy neutrinos," she told BBC News. "[It will mean] we can start understanding the physical processes in the Milky Way better."

The data was collected by the IceCube observatory - a detector frozen into ice at the South Pole

Prof Kurahashi Neilson added that the team would spend the next 5-10 years trying to answer questions that "we can finally ask".