Thames Tideway Tunnel super sewer completed

- Published

The tunnel is wide enough to fit three buses side by side.

After eight years in the making, London's £5bn super sewer has been completed.

Known officially as the Thames Tideway Tunnel, it has been designed to reduce the amount of raw sewage that flows into the river.

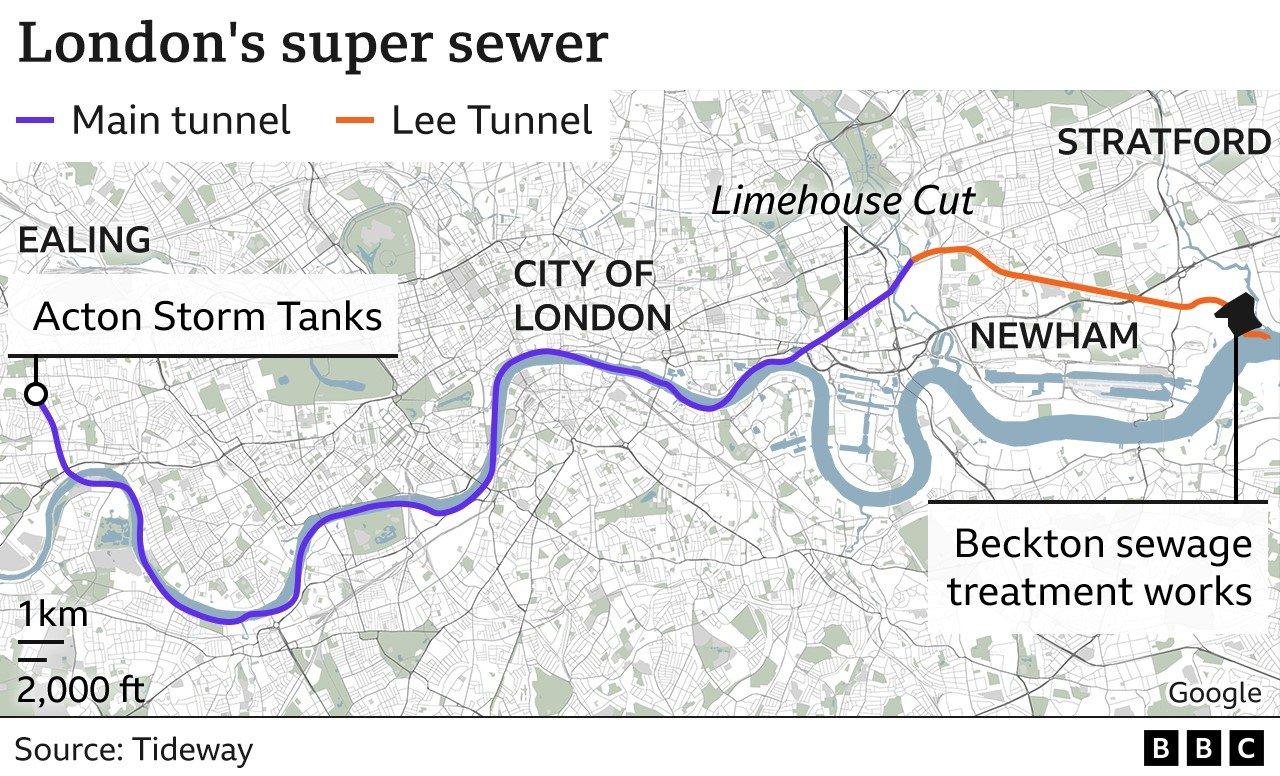

The 16 mile (25km) long pipe will divert 34 of the most polluting sewage outflows (CSO's) that have been discharging into the Thames.

Critics say with climate change the tunnel may have a limited lifespan.

"This is the moment we've all been waiting for," Andy Mitchell the CEO of Thames Tideway told BBC News from a boat above the tunnel on the Thames.

"We're going to capture the vast, vast majority of the sewage that comes into the river and it will mean a cleaner river," he says.

In the final step of construction, a huge 1,200 tonne concrete lid was lifted onto a shaft in east London.

London's combined sewage system handles human waste and rain runoff together, but the capital's population has outgrown the infrastructure.

Raw sewage under normal conditions goes to wastewater treatment plants but currently, even a small amount of drizzle in London can overwhelm the network, triggering overflows into the Thames.

The new super sewer will mean that instead of flowing into the river, almost all sewage overflows in the centre of London will be stored in the tunnel until it can be processed.

The first sewage is expected to flow into the tunnel this summer and it should be fully operational in 2025. Initially expected to cost £4.2bn, the tunnel has ending up costing about £5bn. That cost will be paid for by Thames Water customers over several decades with bills increasing by about £25 a year.

The 7.2m (23ft) wide tunnel flows steadily downhill from Acton in west London to Abbey Mills in the east and during periods of sustained rainfall it will fill up with a mix of raw sewage and storm water.

It can hold 600 Olympic sized swimming pools of liquid which will then be pumped to Europe's largest sewage treatment works at Beckton in east London.

After testing over the summer the super sewer will be handed over to Thames Water, a water company about £15bn in debt and dogged by constant rumours of financial problems. So why should they be trusted to run the super sewer?

"We have had our challenges. It's absolutely fair to say that." Tessa Fayers, Thames Water's operations director for Thames Valley and Home Counties, told BBC News.

"But I think one of the things if you go back in our heritage back to the 1800s Thames Water is phenomenal at delivering infrastructure solutions that provide fantastic sanitation services to the city of London."

Though the super sewer is one of the biggest upgrades to London's sewage network since it was built by Joseph Bazalgette in the 1860s, it is unlikely to be a permanent solution.

Scientists predict that climate change will bring more intense rainfall to the UK, meaning there will be times when even the huge super sewer fills up.

Theo Thomas of London Waterkeeper doesn't think the money has been well spent.

"The super sewer is a massive, expensive pipe and I think the Victorians would be a bit embarrassed that we haven't come up with a more modern solution than that," says Theo Thomas from campaign group London Waterkeeper.

Mr Thomas would rather the money had been spent right across London on projects that stopped rain flowing directly into drains where it mixes with raw sewage.

"You could use nature to be dealing with this. You could have lots of areas that would soak up the rain rather than rush it off the streets and rush it off the roofs straight into the sewers."

The view is at least partly shared by Thames Tideway's Andy Mitchell. Though he says it simply wasn't feasible to quickly and affordably build London a new network that separated out sewage and rainwater.

"Without the super sewer, this spilling of sewage into the river was just going to get more and more frequent and in bigger volumes, and that's what we've addressed," he says.

"What we've done is bought London time. Fifty, sixty, seventy years to do something more intelligent with rainwater than simply mix it with sewage."

Related topics

- Published12 September 2014

- Published3 July 2023