The guidebook that led me to a lost corner of England

- Published

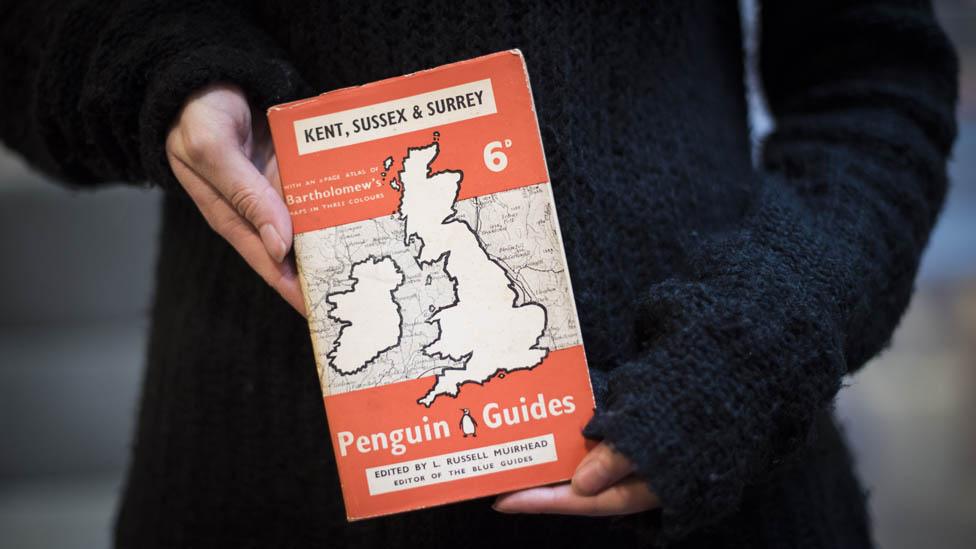

In 1939, the newly established Penguin Books decided to branch out from its trademark paperback fiction and Pelican non-fiction titles to try its hand at UK travel guides. Emma Jane Kirby visited Kent with a first edition of one of the guides in her hand, to see how much Britain has changed since World War Two.

Sitting stationary in my car in what should be the fast lane of the M25, I glance down at the orange-and-white cover of the 1939 Penguin guide to Kent, Sussex and Surrey on the passenger seat. And I wonder whether its author, S E Winbolt, is looking down on me smugly, reminding me that his suggested route out of London was by "Blackheath and Shooters Hill and thence on the straight Roman Road through Welling and Crayford to Dartford".

I'm due in Gravesend at 10:30 but as I'm early, I pull in to Dartford for a coffee, promising myself I'll have a quick glance at the brasses and the alabaster black-and-white marble monument in the church that my guide says I shouldn't miss. I try the church door handle confidently and am surprised when it resists my push.

"Always locked," says a Polish man drinking a can of beer in front of the shop next door. "No safe to leave church open these days."

Before I'd set out on my tour, I had spoken about the books to James Mackay from the Penguin Collectors Society.

"They're great fun," he told me. "Partly because they reflect a society that's no longer there. They have become social history documents of their own. Remember the counties south of London were geographically and socially much more separate in 1939, with their own economies."

I think about Mackay's words as I walk past the charity shops and pound stores that cluster near the church end of the High Street. My guide has asked me to note the "timbered houses" - I don't spot many, although the Georgian-built Bull Inn - albeit under a new name - still serves me a good coffee. I mention to a fellow customer that the town seems very quiet to me and he shrugs.

"Commuter belt. Everyone works in London, don't they?"

Winbolt confidently informs me in the guide that in this area I am to find "modern powder mills, chemical works and manufactories of general machinery".

Local historian Christoph Bull roars laughing when I tell him what I'm expecting. We are in Gravesend, east of Dartford, and I'm joining Bull on one of his popular walking tours of the area. He reminds me that in 1939 the popular Bluewater shopping centre near Dartford was still a quarry and adds that almost all the local industry that Winbolt saw - except for a paper mill making toilet rolls - has now gone.

"Dartford was a town that made things," he remembers. "It created and designed things. It was a pioneer in pharmaceuticals and medicine. But by 2002, the big factory that had opened in 1889 was demolished and it's now being built up with masses of housing."

Bull stops his tour outside the impressive Gurdwara Sikh temple, explaining to his tour group that it's one of the largest Sikh temples outside India.

I ask an elderly group member how the area has changed over her lifetime and she doesn't hesitate before replying: "Foreigners. So many foreigners now. And all the shops and people have gone."

At Loddington Farm near Maidstone, James Smith, whose family has been farming here since 1882, says that without a foreign workforce, his apples, pears and cherries just wouldn't get picked.

"In 1939 my grandfather would have had horses pulling sledges in the orchards and there would still be sheep grazing," he says. "We'd have had 20 local people living and working full-time on the farm. Today I've got two full-time English staff and the rest are transient pickers from Eastern Europe."

I tell him how my guidebook waxes lyrical about Kent being the "garden of England" with its hops and cherries, and Smith replies that very few hops are grown in the area these days. The cherries have changed too, after careful breeding programmes to make them bigger, sweeter and better able to meet the demands of the modern supply chain. So have the apples - gone are the Lord Derbys, Coopers and Bramleys, and in their place are orchards of New Zealand apples like Royal Gala and Jazz.

As I ask Smith what his grandfather would have made of such changes, we're interrupted by a loud roaring noise. Above us, a Tiger Moth biplane circles the farm. Smith laughs - his grandfather used to fly Tiger Moths in 1939.

Unlike a modern travel guide, the authors of the 1939 Penguin county guides do not offer the holidaymaker a list of bed and breakfasts or recommended restaurants. The emphasis, as James Mackay from the Penguin Collectors Society points out, seems to be "not so much on getting out and doing things, but rather just getting on to the next place".

As well as assuming a certain level of knowledge from readers and a desire for personal improvement, the guides also expect their readers to share more or less the same views. They can be "quite judgemental and not just objective and factual", says Mackay.

Find out more

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's report from Kent at 13:00 on 26 December on BBC Radio 4's The World at One

Or catch up later on the BBC iPlayer

Take, for example, the lament of Winbolt in wishing that "Kent coal had not begun to disfigure with its collieries… the sequestered countryside West of Deal".

There's an understandable flash of irritation in Jim Davis's eyes when I read this phrase out loud to him. Davis was Kent's last working miner and he spent over 30 years working underground. We meet in the village of Aylesham, built specially in the 1930s to house Kent's mining community.

"People forget we had pits here at all," he says. There were four pits open in the county in 1939 and they employed hundreds of men from all over the country, including his own father who travelled from Wales.

Jim Davis

"Kent became a melting pot," he says. "We ended up with our own dialect. Even today you can always tell a person from Aylesham because they have a nice soft accent that's a mixture of Geordie and Welsh."

Our Penguin guide may have tut-tutted at the scars that the pits left on Kent's landscape but now a big mining heritage museum is being planned at Betteshanger to make sure no-one forgets Kent's role in the coal industry. Davis is a trustee.

In the beautiful town of Sandwich, where I take lunch, Winbolt seems much more at home in the "quaint, narrow, irregular streets curving aimlessly hither and thither". I try 15 times or so to record myself speaking on the main street but roaring, throbbing traffic and an enormous party of German tourists admiring photographs in the estate agents' windows drown out my voice at each attempt.

"At Sandwich, the wheel of life swings slow," claims Winbolt, before adding sniffily: "Except at the hours when tourists descend from big coaches in the market place."

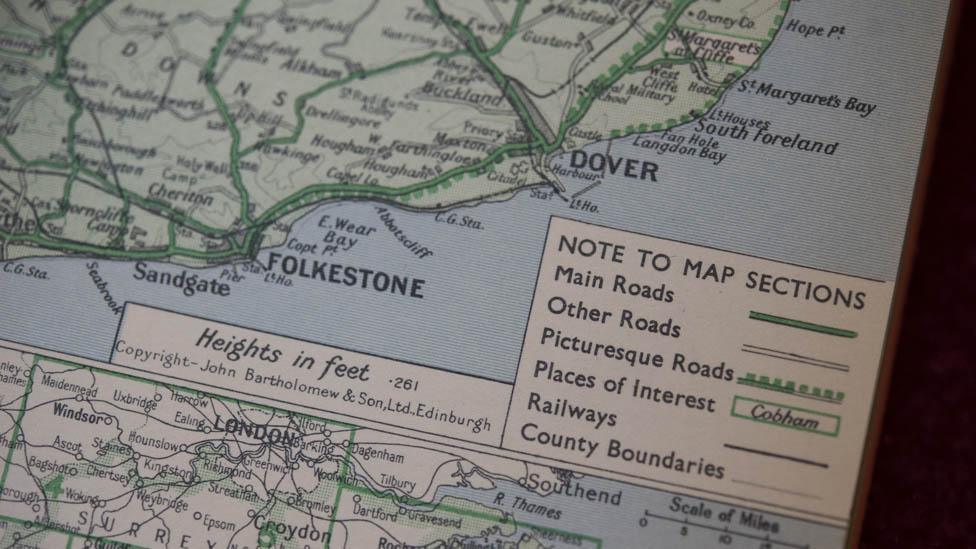

Driving south towards Dover, where my guide promises that "chalk hills and sea breezes combine to invigorate", I'm struck by how many signs there are for the Channel Tunnel and ferry terminals, and imagine how different the holidays of our 1939 travellers would have been had the tunnel existed pre-World War Two. In an uncharacteristically indulgent moment, Winbolt suggests I take a picnic and sprawl on a rug overlooking the sunny channel.

And it's here on the top of the white cliffs, at the National Trust park overlooking the ferry terminal, that I meet journalist and Dover freeman Terry Sutton.

Terry Sutton

"The beach and seafront were so peaceful when I was a 10-year-old child in 1939," he reminisces. "Now we have the A20 running alongside it and 2.5 million lorries coming through Dover every year."

Terry remembers being sent to the shops as a small boy when there were 28 bakers in Dover's town centre, 25 butchers and 40 greengrocers. Now, he says, it's all "nail bars and tanning salons".

Dover's population has dwindled since World War Two - the garrison and pits meant that in 1939 there were some 40,000 inhabitants, whereas today there are only around 30,000. Air travel, Terry reminds me, killed Dover's importance.

"In 1939, anyone who was anyone came into the country via Dover - and they were often wealthy people… but after air travel, the port lost its importance. The lorries bring wealth, of course, to the area, but we've lost the tourism, really."

Regrettably, I don't have time to visit the splendid castle today but I tell Terry I will just whizz past the Regency terraces on the seafront, which my guide recommends, before I leave. Terry shakes his head.

"A lot didn't survive the shelling and bombing," he warns me. "You'll still see lots of little holes all over this town where properties got destroyed."

The sun's out now as I stroll across the shingle beach and a few hardy swimmers are braving the water, while little boys with fishing nets tentatively search for crabs and seaweed. A small child cries inconsolably as her ice-cream cone tumbles from her pushchair and someone, lying on his back against the warm pebbles, is whistling a nursery rhyme. Suddenly 1939 doesn't seem that long ago.

But how poignant for those holidaymakers of 80 years ago, perhaps proudly clutching their brand new Penguin guides in their hands, that it should all end so brutally with the onset of war. Although they would have been aware of the preparations being made for conflict, the books' authors give us no hint that war is coming. And when it did come, that was the end of the Penguin County guides - they were immediately withdrawn from sale, because of the risk of the detailed area maps falling into enemy hands.

Among the guide's sparse illustrations, an impatient penguin with a walking stick hurries along his friend who's stopped to admire a view or a building. Like their author, perhaps the penguins too knew that the time for holidaying was running out.

"Remember this book is selective, not exhaustive," apologises Winbolt. "And bear with me if some of your favourite villages or routes are not included. There are just dozens to which I should have loved to guide you."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.