The mystery of the homesick mechanic who stole a plane

- Published

In 1969, at the height of the Cold War, a mechanic in the US Air Force stole a Hercules plane from his base in East Anglia and set off for the States. Just under two hours later, he disappeared suddenly over the English Channel. Did he simply crash or was he shot down?

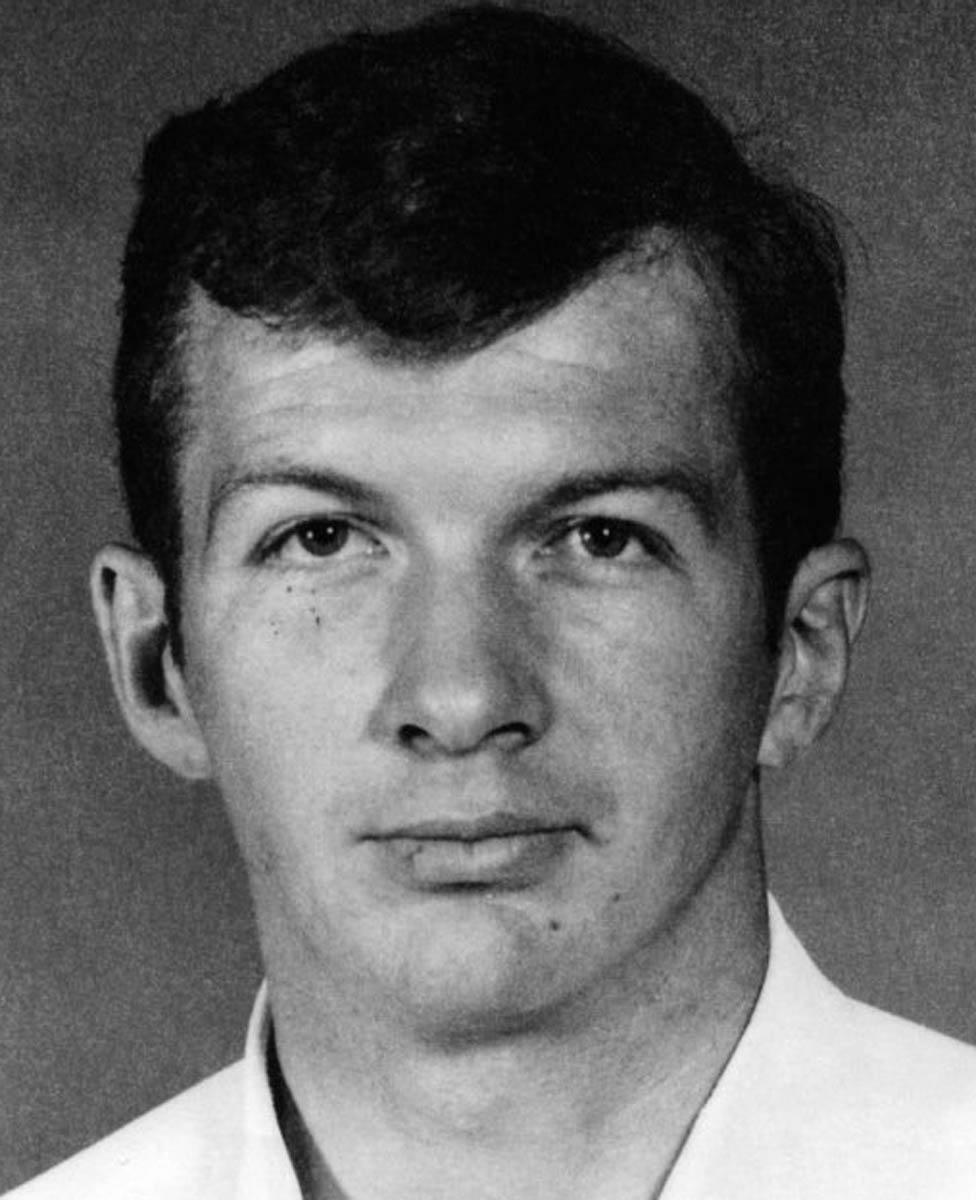

The evening of the 22 May 1969 had not been a good night for 23-year-old US Air Force mechanic Sgt Paul Meyer. Homesick for his wife and stepchildren, he'd asked a few days earlier to be returned from RAF Mildenhall in Suffolk, where he'd been posted, to the USAF base at Langley, Virginia. But his request for leave had been refused.

Bitterly disappointed, the young Vietnam veteran took himself off to a military colleague's house party, where he began drinking heavily and then, according to colleagues, to behave erratically and combatively. His friends persuaded him to go to bed, but Meyer escaped through a window.

Soon after, Suffolk police found him wandering the A11 road and arrested him for being drunk and disorderly. He was escorted back to his barracks and told to sleep it off. But Meyer had other ideas. Big ideas.

Breaking into the room of a Capt Upton, Meyer stole the key to his truck. Using the name "Capt Epstein", Meyer then called an aircraft dispatcher and demanded that aircraft 37789, a Hercules transporter C-130, be fuelled for a flight to the USA.

Find out more

Simon Cattlin's painting of Meyer's Hercules

Listen to Emma Jane Kirby's report on the mystery of Sgt Paul Meyer for BBC Radio 4's PM at 17:00 on Wednesday 18 April

The ground crew obediently followed their superior's orders and the bogus captain climbed aboard, released the brakes and taxied hurriedly from the hardstand towards runway 29. His engines roared.

Completely alone in the cockpit of the stolen 60-tonne, four-engine military transporter plane, an aircraft he was not qualified to fly, the 23-year-old serviceman steeled himself and thrust his throttles forward. Shortly before 05:10 on the dawn of the drizzly, overcast morning of 23 May, he was airborne.

It would have been just after midnight in Virginia, USA when Mary Ann "Jane" Meyer was woken by the telephone ringing.

"Hi honey!" chirped the excited voice of her young husband Paul after she picked up the receiver. "Guess what? I'm coming home!"

Rousing herself from deep sleep, Jane Meyer mumbled something congratulatory and asked him when exactly he and his crew would be returning.

"Now!" he replied triumphantly. "I got a bird in the sky and I'm coming home!"

Jane froze. "You?" she asked incredulously. "You are flying the plane? Oh my God!"

Mary Ann Jane Goodson tells Emma Jane Kirby how her husband called from the stolen aircraft on Radio 4's PM programme

Nearly 50 years on, Mary Ann Jane Goodson, as she is now called, says that conversation, which lasted for more than an hour, still plays over and over in her head.

When she understood that Meyer had gone Awol and that he had stolen the Hercules, she begged him repeatedly to turn back, warning him he'd be severely punished by the military. She cannot remember the last words she said to her husband but she does remember his last words to her very clearly.

"Babe," said Meyer across the radio he'd patched through from the cockpit to the phone network. "I'll call you back in five. I got some trouble."

The line went dead. After an hour and forty-five minutes in flight, Meyer crashed into the English Channel.

A few days later, small pieces of wreckage of the Hercules, including a life raft washed up near the shores of the Channel Island of Alderney. The mechanic's body was never found.

"Why did he crash like that?" Jane asks quietly. "You know, The US Air Force never told me he'd crashed - no one told me he'd crashed - I just got a telegram to say the plane was lost… When he told me he was in trouble, I've surmised the trouble must have been jets that were sent up to take him down… I'm sure I've not been told the whole truth. "

In 1969, of course, the Cold War was at its height. The official US Air Force report into the accident mentions that an F-100 jet fighter was scrambled from RAF Lakenheath shortly after Meyer took off "in an effort to assist him", along with a C-130 from RAF Mildenhall. They were both apparently "unsuccessful in establishing visual or radio contact with him".

Yet Jane says that 20 minutes into her cockpit conversation with her husband, a man's voice came across the line and asked her to keep talking to her husband because they needed to find out where he was.

Hansard, the verbatim reports of proceedings of the House of Common and House of Lords, shows the then-MP for Bury St Edmunds, Eldon Griffiths, demanded to know why the enormous plane was not picked up by US or British radar "for some considerable time".

A robust reply is recorded by John Morris, the minister of defence for equipment, who assured the concerned MP that the Americans informed the Air Defence Operations Centre of RAF Strike Command within minutes of the unauthorised take-off. UK air traffic control had picked up the rogue aircraft on radar within three minutes of take-off, he told the Commons. Jane says her husband told her from the cockpit that he was deliberately flying low to avoid radar detection.

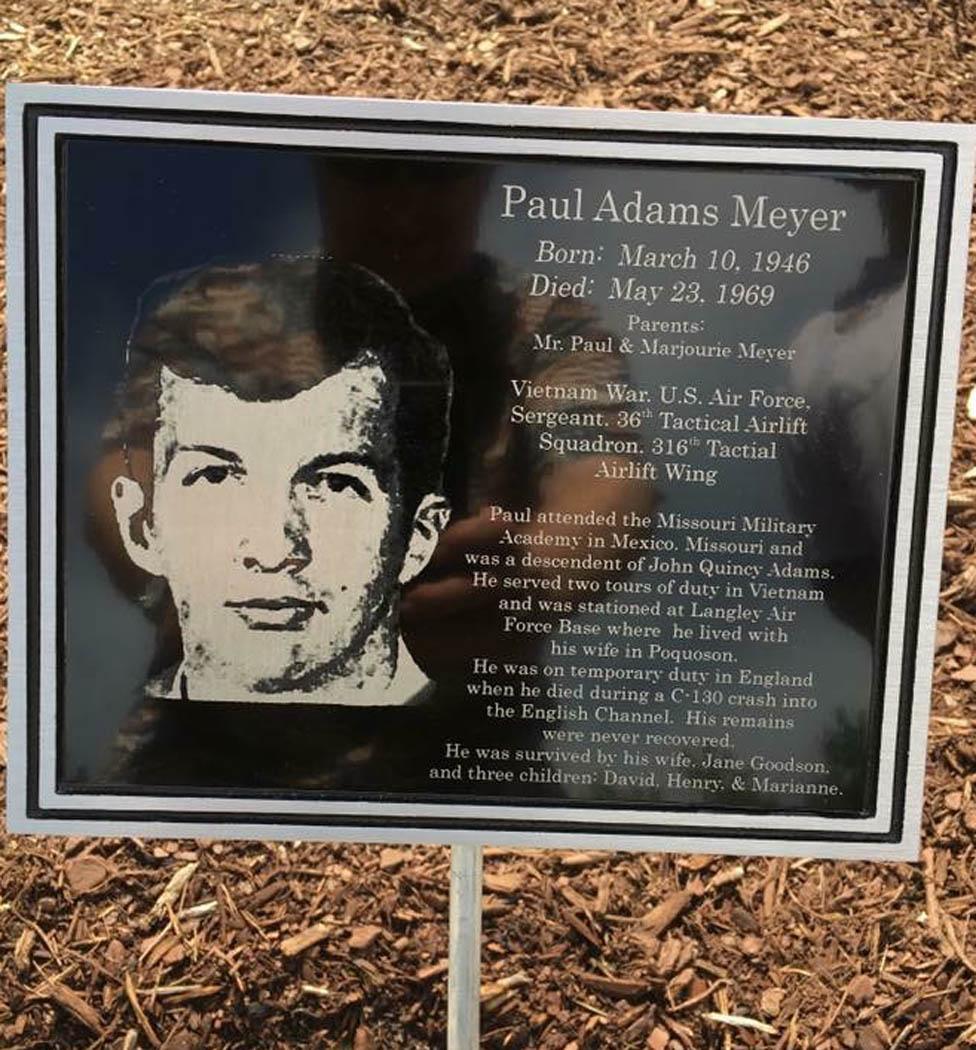

Henry Ayer was just seven when his stepfather was lost over the Channel but still becomes extremely emotional when he recalls the day the Army chaplain came to see his mother to tell her that her husband was lost. The couple had been married for just 55 days.

"I remember my mom just collapsed to the floor like a rag doll," Ayer chokes. "You know, Paul was just a good guy who gave us kids much-needed stability in our lives. He was really mature for his age - he took us hunting, walking the dog together, he sat us round the table at family dinners. So to think our government may have had a hand in it (Paul's death) - well, it's troubling."

The official US report into the accident describes Meyer rather differently - as a man "under considerable emotional distress" who was angry that he'd recently been passed over for promotion.

For the past 30 years, Ayer has battled to get more information from the American authorities. He claims that evidence he twice presented to a USAF attorney was lost and that the subsequent Freedom of Information requests he directed to the USAF were batted away to the CIA, which it said had operated the Hercules. His FOI requests to the CIA have simply been met with silence.

Henry Ayer at a memorial to his stepfather

I remind Ayer gently that his stepfather was not qualified to fly the stolen Hercules and that a terrible accident could have ensued if Meyer had crashed onto a village, a school, or a hospital. Might Ayer understand, I ask, if the USAF had ordered the plane to be shot down at sea in the interests of "damage limitation"?

"Absolutely," says Ayer, who still regularly visits a memorial to his stepfather.

"We would be understanding of that. But we need to know conclusively. We need the government to be upfront."

Thousands of miles from Virginia, on a sullen, dank morning in Weymouth, Dorset, Grahame Knott, a seasoned dive charter boat operator, lowers camera and sonar equipment over the stern of his 13m boat.

For 30 years Knott has been diving and studying wrecks on the seabed with Deeper Dorset, a group of divers, and for the past 15 years, he has read everything he can on the story of Paul Meyer, which he admits has "completely sucked" him in.

Grahame Knott

Now, after a successful Kickstarter campaign to raise money for fuel costs, Knott is sailing his boat into the Channel to search for what's left of Aircraft 37789. So does he suspect Paul Meyer was shot down?

"There are enough conspiracy theories out there already without adding to them," he says, waving his hand dismissively.

"We just want to try to find the aircraft. Some people say, 'Well, what's the point? What's it going to tell you?' And the truth is, we don't know. But leaving it lost in the Channel isn't going to tell us anything, either. So the first thing to do is simply to look for the aircraft."

Knott takes me out to Weymouth Bay and hovers the boat over the site of an old World War Two wreck to show me how his sonar equipment can interpret the dark images of scarred seabed that appear on his screens.

To prepare for his search for Meyer's C-130 in the Channel, Knott has spent 10 years studying tidal movements, official records and examining reports from trawler and fishermen who've caught military hardware in their nets. Knott is now confident he has identified five hotspots within 10 sq miles where the remains of the Hercules may lie. Anything he does find, he's not allowed to remove or lift from the site but he can take extremely detailed images, which he could then show to an air accident investigator.

I tell him that during my conversation with Meyer's widow, Jane, she told me she hoped Knott might find her "sweet Paul's wedding ring or wallet."

He winces.

"That would be a miracle," he says apologetically. "I think the Hollywood idea of finding a fairly intact aircraft on the seabed with bullet holes in the tail - it really isn't like that. But I am confident we will find some wreckage, hopefully a propeller that will tell us something about the impact and what the plane was doing on impact."

In his west London atelier, aviation artist Simon Cattlin is putting the final touches to his oil painting of Meyer's Hercules, which has been commissioned by Deeper Dorset for the airman's family.

There's a terrible sense of foreboding in the scene, with the enormous khaki aircraft flying underneath a threatening black sky. From the cockpit, a tiny vulnerable, pink face is just visible.

"Can you imagine it?" he asks me. "Here was a guy who was a private pilot flying this massive military aircraft completely alone and in bad weather. When I was painting, I was wondering what was he thinking about in that cockpit as he flew over the Channel. He'd have had daylight working for him but not much else."

Cattlin is a private pilot himself and has researched in great detail the meteorological conditions of the morning that the plane went missing. The low cloud, rain and an approaching pressure front, says Cattlin, explain why Meyer didn't just head west immediately to set his course for the States but instead flew south to the Channel.

"If he'd gone immediately west he would have had the terrain hazards of the hills and mountains in Wales," Cattlin tells me, washing the dark paint from his brush in a jam jar of water. "Over the Channel he would have had clear visibility. As a pilot, I would have done the same myself."

Although Meyer was not qualified to fly the Hercules, he was extremely familiar with the plane as its chief mechanic. During our chat together, Jane told me that when flying with his crew, her husband would often be given a turn at the controls. He'd even call her on the radio, claims Jane, while he was flying.

But although Meyer was flying below the cloud level over the Channel, at some point he would have had to start the climb into thinner air for fuel efficiency if he was to make the 3,000-mile journey to Virginia. Could it be that as he climbed into a thick cloud deck, with a head still addled with drink and lack of sleep, that he simply lost control?

"Yes," confirms Cattlin. "With visual cues gone, he could have gone into an uncontrolled descent and hit the water and exploded."

He smiles and looks at his painting pensively for a few seconds.

"But he'd been flying for 90 minutes and there are no reports that he was flying out of control. He'd shown competency and shown he had a plan. I wouldn't say he'd done a good job - you can't say what he did (stealing an aircraft) is a good job - but I'd say he was credible as a pilot."

In their home in Virginia, Ayer and Jane reminisce about watching reports of the crash on the news and in the papers.

On both sides of the Atlantic at the time there was a public feeling of great unease that a drunk mechanic had been able to steal a military plane and fly it for over 90 minutes through British airspace. Incredibly, 11 years previously, another US mechanic had taken off in a B45 bomber from Alconbury base in Huntingdon, and had crashed his aircraft onto the London to Edinburgh train line.

In the May 1969 Hansard entry, the MP for Bury St Edmunds reminded the Commons of the 1958 theft and warned that as Meyer had skirted dangerously close to Heathrow, the British government must be provided with a transcript of the USAF inquiry hearings into the incident. The minister for defence retorted that it wasn't necessary.

The press was given few further details of the crash and the story was shut down. But over the past 49 years, fantastic rumours and wild conspiracy theories have sprung up in forums and internet chat rooms across the world.

Some say the plane had to be shot down because, as a CIA-operated aircraft, it would have contained secret documents - while others suggest Meyer survived the crash and went into hiding, perhaps somewhere in the Eastern Bloc.

As he prepares his small boat for its first official Channel search mission, Knott tells me he thinks the pervading fog of gossip and hearsay suits the USAF.

"I can't think of anything that prevents the truth from being told at this stage, nearly 50 years on," he says. "I just hope someone will pop up with more information and give the truth - who is it going to hurt now?"

For Jane and Ayer, Knott's Channel search is their last hope of getting what Jane terms as "some closure".

"He was having bad nightmares about Vietnam," she confides as we end our conversation. "We wrote to each other every day and we marked the days off a calendar. You know, he just wanted to come home. All he wanted was to come home."

Further reading

On 1 January 1985 a passenger jet crashed into a mountain in Bolivia killing all 29 people on board. No bodies were ever found. Nor were the black boxes that would have revealed the cause of the accident. But last year two young Americans decided to have a look themselves - and ended up achieving far more than official investigators.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.