The 'Belsen boys' who moved to Ascot

- Published

Shortly after the end of World War Two a group of young Holocaust survivors was flown to the UK to recuperate. Thirty of them were housed in the Berkshire town of Ascot, famous for the pomp of the Royal Ascot horse races, where they made an incongruous sight, writes Rosie Whitehouse.

Margaret Nutley remembers her first meeting with a group of unfamiliar boys on the Ascot racecourse. It was autumn 1945, and they were playing football, wearing striped jackets from a concentration camp.

"The course was not fenced off as it is today and us local children used it as a playground. One day I went up with my friends to muck about and there they were. They were just there, playing like the rest of us.

"The boys showed us their tattoos and talked about what had happened to them, but not boastfully."

Nutley, now 85, noticed that they were "happy people", despite what they had been through.

"People don't understand. They were not downtrodden and broken but proud that they had survived, and not shy to say so," she says.

"They were very friendly, chatty… They were the lucky boys."

Children are no longer able to play on Ascot racecourse

When Nutley recently shared her memories in a group chat on Facebook, she was ridiculed for suggesting that three boys had been wearing their striped camp outfits. But her recall is sharp, and in fact many concentration camp survivors kept items of clothing as proof of what they had endured. They were proud of the jackets and trousers that symbolised their survival and it seems likely that they wore them to identify their team when they played against local boys.

Two of the teenagers may well have been 13-year-old Ivor Perl and his 15-year-old brother, Alec. Born in the small town of Mako in southern Hungary, they had survived Auschwitz and a death march to Dachau.

Then, in the autumn of 1945, they had been flown to Southampton and brought to recuperate in Ascot.

Perl, who now lives in Essex, remembers that he met some girls on Ascot racecourse and "took a fancy" to them, but he cannot remember their names.

Ivor Perl, nearly 73 years after he was first flown to the UK

The brothers were among several hundred children, mostly boys, who were offered a helping hand by the Central British Fund (CBF), the same organisation that had arranged the Kindertransport bringing 10,000 predominantly Jewish children to Britain in the months before World War Two.

At least 1.5 million Jewish children had been murdered in the Holocaust, but after the war the CBF lobbied the government to grant visas to the few thousand who had survived.

The Home Office agreed to allow 732 into Britain for two years' rehabilitation - but only on the condition that they would not cost the taxpayer a penny. The money to care for the teenagers was raised by the Jewish community.

After liberation at Dachau in April 1945, Perl was skin and bones and close to death from typhus. Once he had recovered, he and his brother prepared to go home to see if their parents and seven siblings had survived. But when informed by the Red Cross that they were the sole survivors of their family, they thought again and decided instead to go to Palestine, which was then under British control.

There was a problem with this plan too, though.

"The authorities caring for us in Germany explained that the British were blocking immigration to Palestine and we should apply for visas to the UK," Perl says.

He jumped at the idea. "England was like the golden land," he says. And it was an opportunity to get out of Germany.

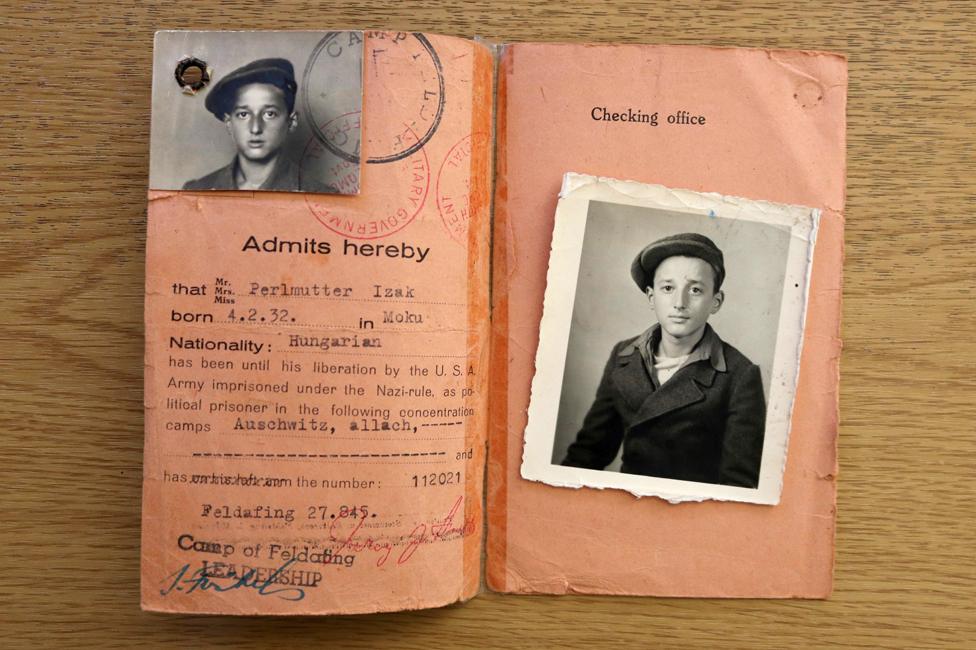

Perl's name in childhood was Izak Perlmutter

The boys were flown from Munich in Stirling bombers and taken to Woodcote House, a large manor opposite Ascot racecourse with large gardens full of rhododendron bushes. It belonged to a member of the local council and had been used to house Jewish evacuees during the war.

In charge of the 30 boys there was Manny Silver, a 22-year-old Jew from Leeds. Silver, whose father had been born in Poland, found the boys little different from himself except that the 21 miles of the English Channel had saved him from their fate.

Silver had no training and no assistance from psychologists but in his team were young German Jews who had arrived on the Kindertransport several years earlier.

Rehabilitation started with the basics. The boys had to be taught table manners. Their experiences meant that every mealtime they sneaked slices of bread from the table to hide in their pockets and under the pillows of their beds, and they had to be persuaded that they did not need to do this.

The emphasis was on the future and providing them with the skills to build a new life. The languages used in Woodcote House were German and Yiddish but the boys were issued with English textbooks donated by the British Council. Silver recalled, many years later, that they "had a devouring need to learn".

A photograph from the Hulton Archive: "Mr and Mrs Ronald Armstrong Jones, wearing formal dress as they attend Royal Ascot, circa 1945."

For Perl, life in England was very different from his upbringing in an Orthodox religious family.

"We did not know what life was really about. I had not seen double decker buses and traffic lights. It was all new!" he says.

"Religion is about restrictions and the lack of someone to tell us what to do was also liberating."

He remembers that they went on trips to the cinema and were given bikes to explore the locality.

One of the letters he keeps in a file that is clearly precious to him describes him as "a cheeky boy."

Some of the boys from Ascot on an outing to Henley

After Woodcote closed in 1947, some of the boys, including Perl and his brother, remained in the UK. But nearly all wanted to go to Palestine, Silver recalled, and when war broke out in 1948 many did, to fight for the new state of Israel.

Perl also considered signing up but was persuaded not to risk his life by one of his teachers. "I thought 'Palestine can wait' as, above anything, I wanted to taste life," he says.

Eighty-five-year-old Irene Baldock's mother, Martha Turner, worked at Woodcote. The family were from London's East End and they had settled in Ascot when their shop in Hackney was destroyed in the Blitz. Her younger sister, Dorrie, spent a lot of time at the hostel playing table tennis with the boys.

Sammy Diamond was one of them, Baldock says, and he was "sweet on Dorrie and spent a lot of time at our home".

Irene Baldock

Both were 18 in the winter of 1945/46, Diamond having lied about his age in order to get one of the visas to the UK, which were intended for under-16s.

He had been in the camps of Buchenwald and Theresienstadt and had flown to the UK from Prague in August 1945 with 300 other young survivors.

According to Baldock Diamond was "very exuberant and had a good sense of humour. He had short dark curly hair and a happy face." He had been born Samuel Diament in the industrial city of Lodz, now in central Poland, and Baldock says his upbringing was similar to hers.

A group of the children in Prague, before the flight to the UK

"Our family was much as his had been and we made him welcome. My mother had worked for a Jewish tailor and we had lots of Jewish friends and neighbours in Hackney.

"He once came back from America where he became a tailor as he wanted to see my mother. He had been separated from his mother in the camp."

Baldock says she would love to know what happened to him and if he had a family.

As children, she and Nutley were both taken by their mothers to see the shocking newsreels of the liberation of Belsen, which led to the Woodcote boys becoming known locally as the "Belsen Boys".

Belsen was burned to the ground after it was liberated, to prevent the spread of typhus

Today both women say they are concerned about history repeating itself. Baldock says she knows children now learn a lot about World War One but fears they are not taught enough about World War Two. If they were, she thinks, it would help them understand the contemporary world, and enable them to see the danger of intolerance.

For his part, Ivor Perl, who has spoken widely about his experiences in schools, is concerned that understanding of the Holocaust in Britain is too narrow.

"People always ask me if I hate Germans, but it was the Hungarian boys I used to play football with in my home town who rounded us up into the ghetto with sticks," he says.

One person who was fascinated to read Nutley's post about the Woodcote boys, is Elizabeth Yates, clerk of Ascot's parish council - who moved to the area from Mill Hill in North London 18 years ago.

"This is not an area normally associated with this kind of tale," she says. "People are always surprised when they discover I am Jewish and often say, 'I didn't think we had people like you in the area!'"

The grounds of Woodcote House have become a gated community of houses

She is keen for the story to be used in local schools, partly because her own children's Holocaust education - which began with the two of them being invited up on to the stage at a school assembly along with two German boys - left room for improvement.

"The teacher gave a brief outline of the Holocaust, and as a result one of the German boys was beaten up in the playground," she says.

"I think we can and should improve on that in Ascot.

"The rediscovery of this story offers us a unique opportunity that should not be missed. Ascot offered the boys hope and a new life. That is a positive message to get across in the present climate."

Photographs by Rachel Judah, unless otherwise indicated

UPDATE, October 2018: : This publication of this story helped give rise to the Ascot Holocaust Education Project, external, which aims to promote understanding of the Holocaust through the story of the 30 survivors cared for at Woodcote House.

After World War Two, the BBC attempted to find relatives of children who had survived the Holocaust - they had lost their parents but it was believed they might have family in Britain. "Captive Children, an appeal from Germany," the radio broadcast begins. One by one, for five minutes, the presenter asks relatives of 12 children to come forward.

With each name comes a short but devastating summary of the child's ordeal under the Nazis.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.