'My lovely dad tried to kill me'

- Published

Robyn Hollingworth was just 25 when she left her job in London to help care for her dad who had early-onset Alzheimer's. Here she reveals the challenges and heartbreak of parenting a parent.

I'm hiding behind the sofa in the living room, sweating profusely and fumbling with my phone.

"Where are you, you little thief?" my dad yells as he comes down the stairs.

"I'm going to kill you, you hear me?"

He comes into the room and I can see he's holding a carving knife.

But suddenly someone knocks at the front door and he goes to answer it. It's the next-door neighbour.

"Hi there! You all right?" she asks nervously.

"Hello there, love!" My dad's voice is all soft and fatherly, not mad and murderous. "How can I help you today?"

"We, uh, heard some noise and wondered if you were OK. Why, why do you have a carving knife in your hand?"

"Well funnily enough, I've just found a burglar in my house, so right now I'm trying to smoke the little ferret out," Dad declares, rather proudly - though he used a stronger word than "ferret".

I can tell my neighbour is scared but is trying to keep him talking. I crawl to the back door, sprint down the garden and hurl myself over the fence.

I walk across town to my friend Kate's house.

She opens the door to my tear-stained face and my frozen, bare feet.

Robyn moved back to her parents house when she was 25

My dad, David Coles, was a charmingly intelligent self-made man. He was a civil engineer and built power stations all over the world. He had a beard and moustache combo that had seen him through the decades, gently fading from mouse-brown to pale grey. I idolised him.

Dad retired in his late 50s, while my mum Marjorie continued working for a local charity. They lived in Pontypool in South Wales. I had moved to London to study at Royal Holloway University and stayed there to work as a fashion buyer. But when I was 24, Mum revealed that Dad had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. A year later I was back at home to help Mum shoulder the care.

One of the first obvious signs, apart from repeating stories, was that Dad's language changed. The F-word began making frequent appearances.

"Dad, you've got your jumper on back to front," I told him one day after returning with Mum from Tesco's.

"Ah, get lost," he replied, except he used the F-word instead of "get lost".

"Don't speak to your daughter like that!" Mum snapped.

"You can get lost, too," he added for good measure.

Sometimes it felt pointless talking to Dad because he was easily insulted. He was often aggressive or defensive with me and Mum, though funnily enough he was very obliging with my older brother, Gareth.

My dad had always spun a good yarn, but as his memory faded he would make things up to fill in the blanks. These untruths could vary from "Yes, I've taken my medicine," to "Ooh, I've had fish for tea." And his behaviour became more unpredictable too.

Once he offered to make Mum a cup of coffee, and came back with a soup bowl of coffee made in the microwave, giving it to her with a tea towel and a spoon.

Find out more

Listen to Robyn speak to Saturday Live on BBC Radio 4

Get the Saturday Live podcast for more extraordinary stories

Another day he called my mum while she was out shopping to ask where his passport was. "Are you planning on going anywhere dear?" she joked. He hung up in response. When Mum got home she found the house had been ransacked. Paper littered the living room, kitchen drawers were hanging out. The drawers in the bedrooms had been pulled out and the contents strewn on the floor. She found my dad, shaking and sobbing in their bed. Later on he mended the drawers and forgot about the incident, but Mum didn't.

It wasn't all doom and gloom. Once I remember spotting Mum out shopping wearing her big fluffy purple cardigan. It had sparkly bits and was embossed with flowers. I raced to catch up with her only to realise it was Dad. He had teamed it with green cords and hiking boots. He greeted everyone brazenly in the Post Office, without a care in the world.

However, a lot of the time I found caring for Dad sad and embarrassing and then I'd feel guilty and disgusted with myself. I had to keep reminding myself he couldn't help being ill. Despite everything, I didn't begrudge caring for him for a second and I never thought of leaving.

David was a keen runner and club rugby fan

A week after the passport incident Dad went out for a walk and didn't come back. After searching the local pubs we called the police. They found him in the hospital - he had been found in the gutter by the side of the road with a large cut on his head. Mum went to collect him and he seemed vaguer than ever.

I was more and more aware how hard it must be for my mum. Physically her husband was the same but his mind had gone.

"Of course, I still love him, in a way," she told me then, during an unusually frank conversation.

"But that is not the person I fell in love with - that's not the man I married."

Five ways to spot if someone has Alzheimer's

Alzheimer's: how much should you reveal?

The part of my dad that dementia can't take

Then, just two months after I moved home, Mum was diagnosed with aggressive skin cancer. It was made more difficult because Dad didn't really understand that Mum was ill.

On the day of her operation he joked in the Post Office that she was getting a boob job. I wanted to hit him with a newspaper. But when we went to see her in hospital I think reality dawned on him, as he didn't want to leave her.

"Come back to me, my love, please come back soon," he whimpered as she stroked his hand.

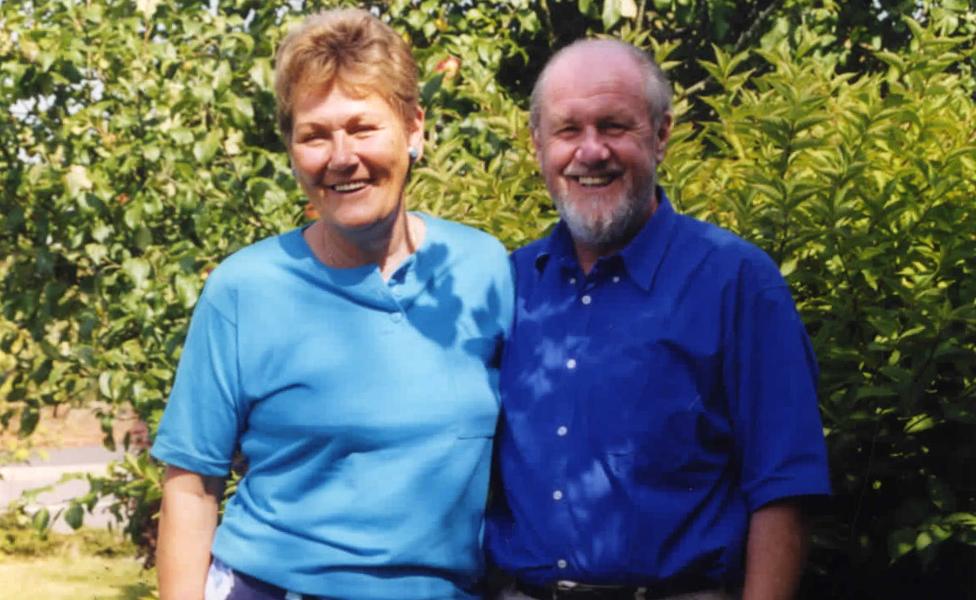

Robyn's parents met in the late 1960s

When we got back to the house he asked me where Mum was.

"Why isn't she back from work yet? Has she gone away?" he asked.

I explained she was ill in hospital with cancer.

"Well that's a shame, I wanted to take her for a walk in the park," he responded.

Despite chemotherapy, Mum's tumours spread and two months after her diagnosis we found out the cancer was terminal. Dad struggled to understand. He would repeat on a loop that he and Mum had had a good innings, with two children and a nice life. At other times he thought she had a stomach bug or was at work, when she was actually resting upstairs.

Mum died at home. The family had gathered to say goodbye to her. She told my brother and me to take care of each other and that she was sorry she was leaving us alone to care for Dad. Despite the awfulness of it, I wanted that moment to last forever. I went downstairs to discover Dad had peeled two whole 2.5kg (5lb 8oz) bags of potatoes. We'd be eating mash for months.

Gareth and Robyn were always close despite the five-year age gap

At the funeral we arranged for a bagpipe player to play Mum into the church. We played Out of Africa at the end, to mark Mum and Dad's travels abroad. I kept a nervous eye on Dad all day, but he was mostly quiet and compliant. At the wake, though, he lost the meaning of what the day was for, and thought it was to celebrate his retirement. When I was outside on the phone he tried to get people to do a conga. When I found out I laughed so hard I cried.

After Mum's death, Dad went downhill rapidly. Apparently changes in routine and security can hugely accelerate an Alzheimer's sufferer's decline. He became disorientated, with little appetite. It was 10 days after the funeral that he confused me for an intruder and chased me with a carving knife.

After I escaped, it was judged too dangerous for me to return, and caring for Dad fell solely on my brother. A fortnight later we decided he needed to go into care. I would visit him with my brother, as I was too nervous to go on my own. Some days he didn't say much and lashed out if I tried to hug him, on others he smiled and seemed happy but didn't speak. My brother was livid one week after a carer shaved off Dad's facial hair in a well-meaning attempt to smarten him up.

Dad caught pneumonia after a few months in care and became gaunt. I will always be haunted by the distressing image of him moaning, without his teeth in, and unable to eat or walk without help. My lovely dad had become a zombie, his wonderful brain was hollow and still. All I could do was sit with him and hold his hand and tell him I loved him. He died just five months after my Mum.

I'm sad Mum and Dad never got to see their son find a partner and have a son of his own, or their daughter get married (my brother walked me down the aisle). It wasn't easy after they died but in my dreams I remember them when they were well and happy and in their prime.

We sold the house shortly after my dad died and on a beautiful summer's day we drove up into the mountains overlooking town. Walking to the highest point we both took an urn and whirling around we spun our parents' ashes into the sky. We watched as they soared from something into nothing - into the ether and everywhere.

Robyn Hollingworth is the author of My Mad Dad: The Diary of an Unravelling Mind

As told to Claire Bates. Claire is on Twitter @batesybates, external

You might also like:

Romy McCluskey's mother said butterflies were a sign she would always be with her after she died.

I fix butterflies to remember my mother

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.