'My daring grandfather took a bit of East Berlin for himself'

- Published

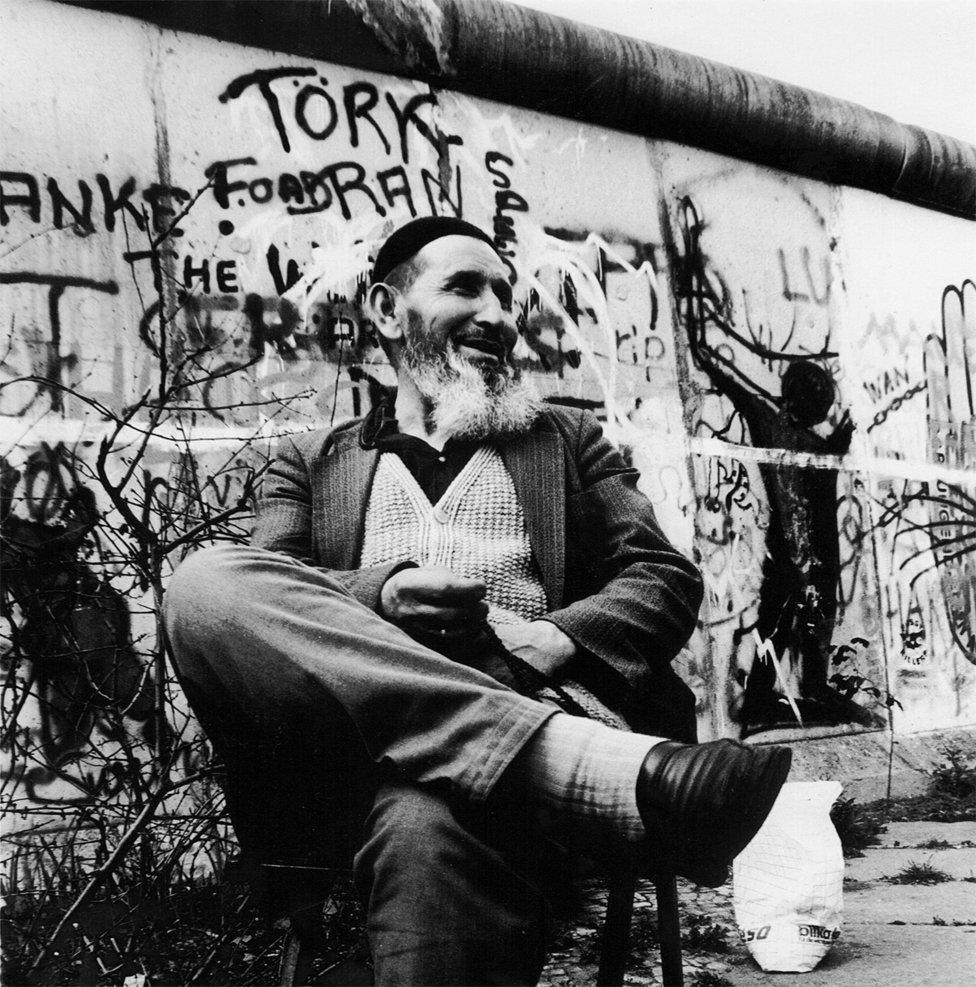

In 1982, a Turkish immigrant started a garden near the Berlin wall on a patch of East German land. Osman Kalin fiercely defended his small domain from any authorities who tried to take it away. Though he died this year, his family are still looking after the plot and the tree house he built there.

"When I was 17, my high school art teacher showed us famous buildings, explaining their historical significance," remembers Osman Kalin's granddaughter, Funda.

"They showed us the Eiffel Tower one week, and the next week they showed my grandfather's tree house.

"The boys in the class made fun of it because it looks a bit funny and misshapen - and being a teenager, I was completely mortified. My friend was about to reveal that it was MY grandfather who built it, when I shot her a look to shut her up."

But that was 16 years ago. Now Funda says she is extremely proud of what her grandfather built.

Funda Kalin in front of the tree house her grandfather built

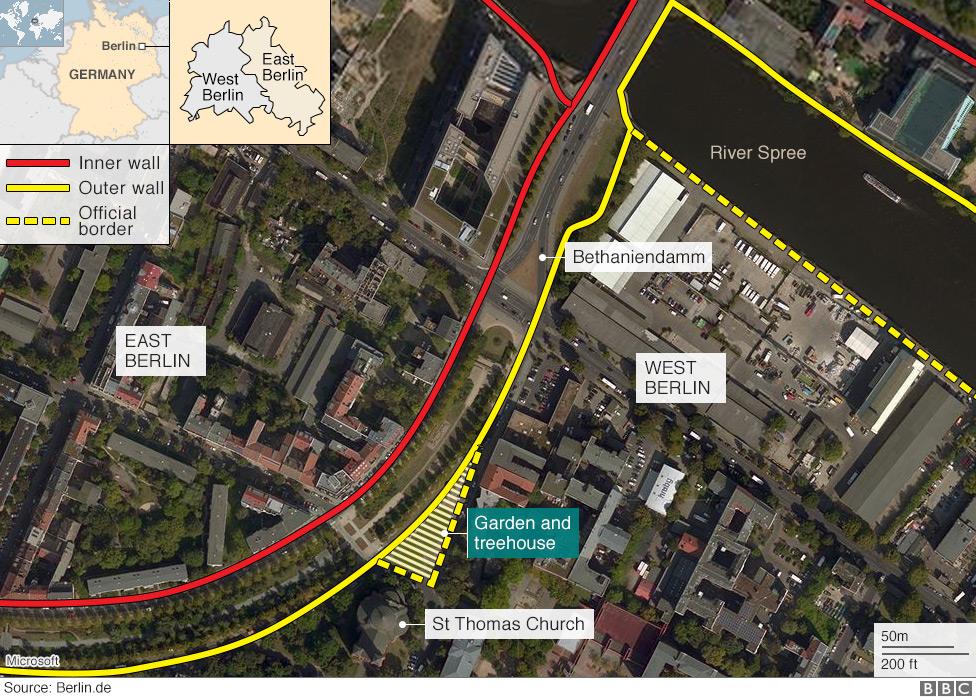

The garden Osman Kalin created stands on the border of Mitte (formerly East Berlin) and Kreuzberg (formerly West Berlin). Modern office blocks and high-rise flats now surround the overgrown garden and topsy-turvy house which is decorated with graffiti, its mismatched furniture cemented to the floor.

But from 1961 to 1989 the Berlin wall divided the area, running along one of the garden's three sides. In fact, it was the creation of the wall that brought the garden into existence.

Berlin residents at the newly-erected Wall at the district border Kreuzberg/Mitte - August 1961

Overnight in August 1961 concrete posts were set in the ground and strung together with barbed wire, while armed guards started patrolling the eastern side with attack dogs.

But the construction workers cut corners. Officially, the border between East and West Berlin traced a right angle near a curved street known as Bethaniendamm, but the wall went straight across, leaving a triangle of East Berlin on the western side of the wall. It remained even when the wire fence became a fortified double wall with a mined and tripwired "death strip" in between.

This meant that nobody could use the 350 sq m plot of land: the West German government didn't own it, and the East German government couldn't get to it.

Pretty soon, the residents in the western neighbourhood of Kreuzberg began to use the area as a rubbish tip, dumping old bits of furniture and washing their cars there.

The huge pile of rubbish sat there for nearly two decades until Osman Kalin, a construction worker from Yozgat in central Turkey, moved into the neighbourhood in 1982. Recently retired, he was looking for a project to occupy his time. But what?

From his flat he could see the eyesore of the rubbish dump and decided to start there. He took it upon himself to clear up all the rubbish, and planted a garden - he just wanted somewhere to grow some vegetables, says Funda.

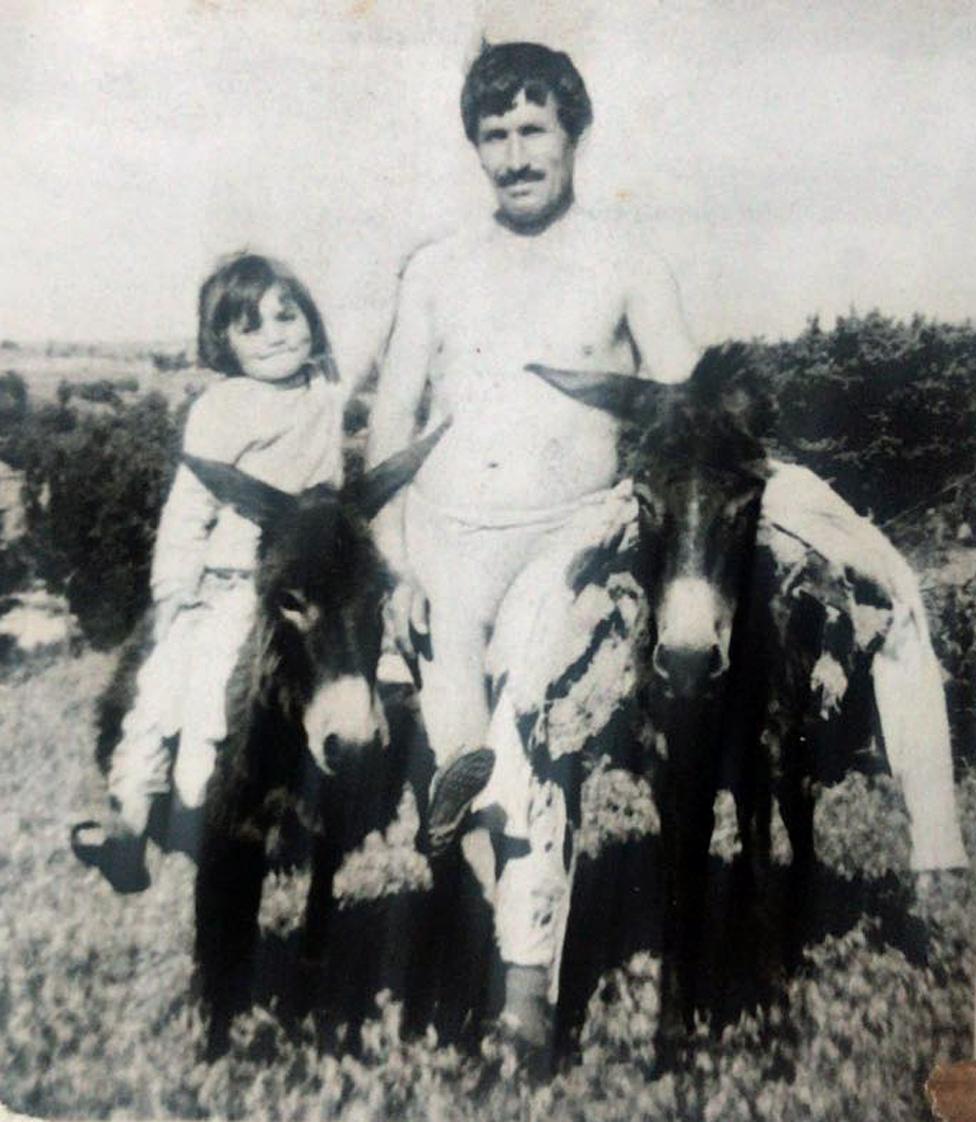

"He had this countryside mentality," Funda says. "He had left behind a big house and land in Yozgat, with donkeys walking around, and there he was cooped up in an apartment - he really wanted to get out and move around."

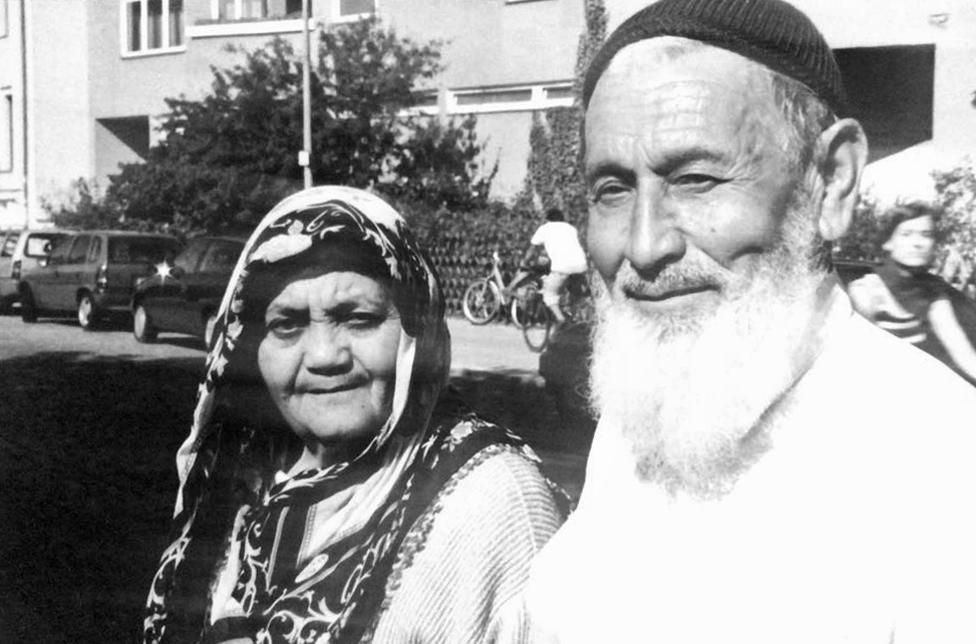

Kalin worked from dawn to dusk on his new project. His wife, Fadik, had to come down from their flat with food to remind him to eat.

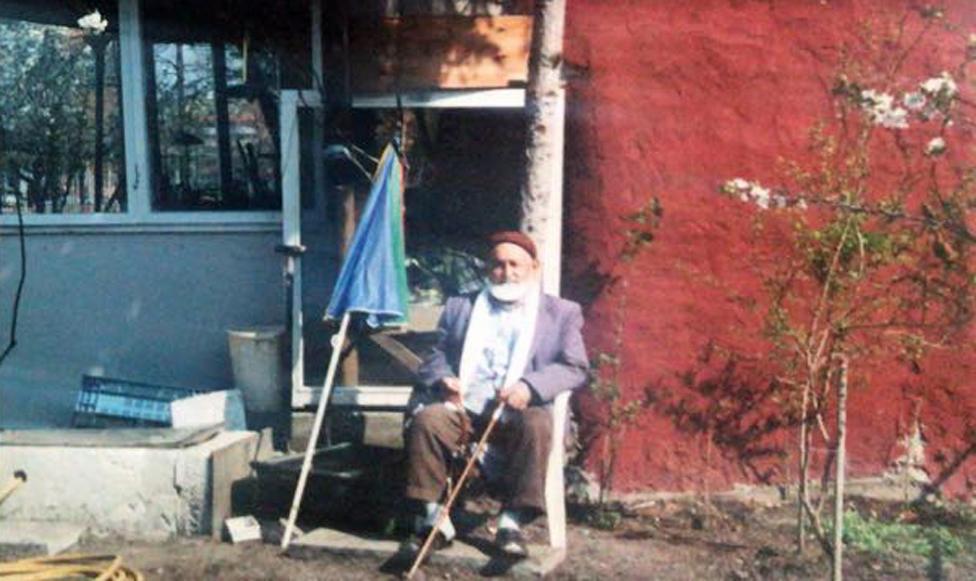

Osman and Fadik Kalin

He planted fruit trees - peaches, apples - as well as his staple crops: garlic and onions.

By then the East German border had armed the wall. It was common to hear soldiers patrolling it with their dogs and to see them in the watchtowers looking over it into West Berlin.

Timeline: Berlin Wall

1948-49: Soviet forces blockade West Berlin, geographically an island in communist-controlled East Germany.

13 August 1961: The border between East and West Berlin is closed. Soldiers start to build the wall. What starts as barbed wire and light fencing builds up over the years into a complex series of wall, fortified fences, gun positions and watchtowers heavily guarded and patrolled. More than 200 people die in the years that follow trying to cross the wall.

1987: US President Ronald Reagan visits Berlin and urges Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the wall.

4 November 1989: A million people attend a pro-democracy demonstration in East Berlin's main square. Within days, the East German Government resigns.

9 November 1989: Thousands of East German protesters go to border crossings demanding to be let through. The border guards stand back as thousands stream into West Berlin. The wall is breached and people begin to pull it down in celebration.

3 October 1990: East and West Germany are formally reunited.

Two weeks after Kalin started digging up the garden, the East German border guards came to visit him to see what he was up to, and to make sure he wasn't tunnelling.

When they saw that he was simply starting a garden they allowed him to use the land, providing that he remained 3m (10ft) from the wall.

Soon after that visit, the West Berlin police approached Kalin, demanding that he move off the land.

"God gave me this land!" he shouted. "I'm not scared of you - you'll have to kill me before you can have my garden."

The East Berlin guards watched this exchange from a nearby watchtower. They could see he was really annoying the West Berlin authorities - so to annoy them even more, the East Berlin authorities made sure that Kalin had free and full use of the land.

A couple living in Bethaniendamm overlook the wall in July 1986

The garden lay at one of the thinnest points of the death strip, meaning that many tunnel and escape attempts were made. Twice Kalin saw people get shot.

The East Berlin guards became used to his presence. Every morning it was part of his routine to wave to them in the watchtower. He also gave them onions.

Each year the guards wrote him Christmas cards, and sometimes even gave him a bottle of red wine.

"My grandfather was a devout Muslim, so he didn't drink. He didn't know that my father would drink it instead," says Funda.

"He was really friendly to everyone, he didn't care if you were a soldier sitting at the top of the wall, or a West Berlin police officer. If you wanted to have garlic, tea or some baklava he invited you to the garden. There were university students who would come and do their homework there."

In the 1980s there was a huge alternative scene in Kreuzberg, and the anarchist punks in the neighbourhood respected Kalin.

"They would come and sit with my grandfather because they thought he was really cool, anti-establishment, fighting with governments for this garden. My grandfather called them his soldiers, and said they would protect him and his garden.

"It was amazing to see," says Funda. "They called him Leo, like 'Lion', because he was so strong and pugnacious."

In 1983, the year after he took over the land, Kalin built a shed, and slowly a two-storey tree house began to take shape around a tree in the middle of the garden. It is fully wired, with electricity and running water, a bedroom and a study. It became known as the Treehouse on the Wall, das Baumhaus an der Mauer.

Funda remembers a childhood of summer barbecues in her grandfather's garden. "He always had fresh onions and garlic in his hands, it was like his salt and pepper. He wouldn't start eating until the onions were on the table. Eating onions - I swear this is why he lived to be so old."

"We use onions and garlic so much in Turkish food and the whole neighbourhood, all the Turkish ladies came to ask him for fresh stuff. He made the garden a little bit bigger and started to sell them at a street market. I remember my grandfather borrowed those baby pouch things, you know where you strap a baby to your front? He filled it with his onions and carried them like his babies to the market every week."

In the beginning, Kalin brought water from his flat to water his vegetables, carrying two containers in each hand. But this proved to be really laborious, so when he found an old pump by a nearby church, he took water from there.

Osman sawing with the church in the background

However, this was not any old pump. It was one of the Landesbrunnen - part of West Berlin's emergency drinking water reserves. It is illegal to take water from them and Kalin eventually got caught. The fine was 600 euros (£530).

As Kalin's German wasn't good enough to appeal against the fine, his son, Mehmet, took it upon himself, as Funda discovered later when she came across a handwritten letter from her father to the officials. It said:

"Hallo, I am very sad because you say to my father, he is a thief. I'm very angry and sad you say to my father, not stole something in his life. He thought he was OK to take some water, for his vegetables, no money to pay you, thank you so much. Mehmet Kalin."

Amazingly, it worked.

"I couldn't believe that the German authorities saw this letter and they just waived the fine! I could have helped my father write a letter in perfect formal German, typed up, and they probably would have pressed the fine anyway, but here they just let him off."

Mehmet and Funda at the house

In 1989 the Berlin Wall came down. Berlin was one city, Germany one country again. Kalin's garden was now suddenly back in Mitte, rather than Kreuzberg.

By then, Kalin was a local hero, an old man known for going against governments, doing what he wanted and getting away with it. People felt that he embodied Kreuzberg's spirit. But in Mitte nobody knew who he was, they saw him merely as a squatter using public space.

The Mitte council decided to evict Kalin, but when the people of Kreuzberg discovered this, they rallied in support, with crucial help from the church of St Thomas next door.

"The priests helped us write letters to the council," Funda explains. "The church provided a document from the 1780s: an old map to show that the garden was on church land, which gave them the right to say that Kalin was allowed to use their land."

The document was more than a century old, and probably would not have held up in court, but the fact that the community protested made the council pay attention.

In the end, the council officially re-drew the border along where the Berlin wall used to run, moving the garden from the district of Mitte into the district of Kreuzberg - its spiritual and (now forever) geographical home.

Kalin died in April, aged 96. As his memory failed in the last 10 years of his life he became more and more irascible, but on good days Kalin relaxed in his garden.

His son, Mehmet, now tends to it and Funda uses the fresh onions and garlic as ingredients for her contemporary Turkish food business. Over the years the Kalins have rejected many offers to buy the land - not that it is theirs to sell. But as its value increases, developers may be harder to stave off.

Kalin's fighting spirit appears to have secured a little corner of history but there was one battle he could not win - with nature itself.

"You can see this tree that grows out the front?" says Funda.

The tree in question is a Gӧtterbaum, or God's tree, an imported species that is fast-growing and invasive - qualities that have also earned it the nickname the "tree of hell".

"My grandfather said, 'I don't need this tree, it takes up so much space.' It's really big and the roots grow through everything. He tried to cut out the roots, fighting for years with this tree.

"The tree is like him, stubborn. He reluctantly accepted it in the end - he decided, 'OK, it has to be here.' It came through the house, broke the walls and now is part of the tree house - just like my grandfather."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.

You may also like:

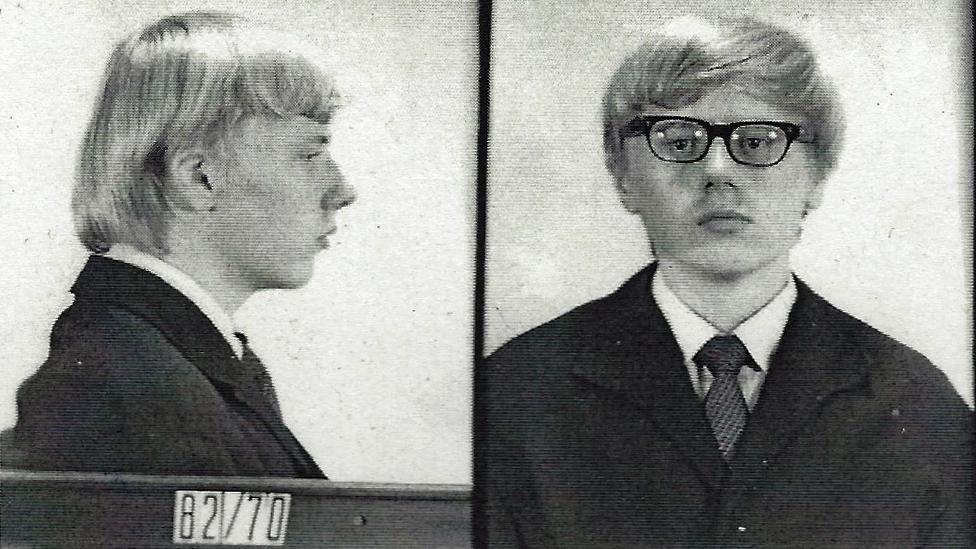

The East German secret police went to extraordinary lengths to track down people who wrote letters to the BBC during the Cold War. One of those arrested and jailed was a teenager who longed to express himself freely - and paid a high price.