Was the newlywed mechanic who stole a plane shot down?

- Published

In 1969, at the height of the Cold War, a homesick, hungover mechanic in the US Air Force stole a plane from his base in East Anglia and set off for Virginia. Nearly two hours later, he disappeared suddenly over the English Channel. Did he simply crash or was he shot down? Emma Jane Kirby has been scouring the archives to find out.

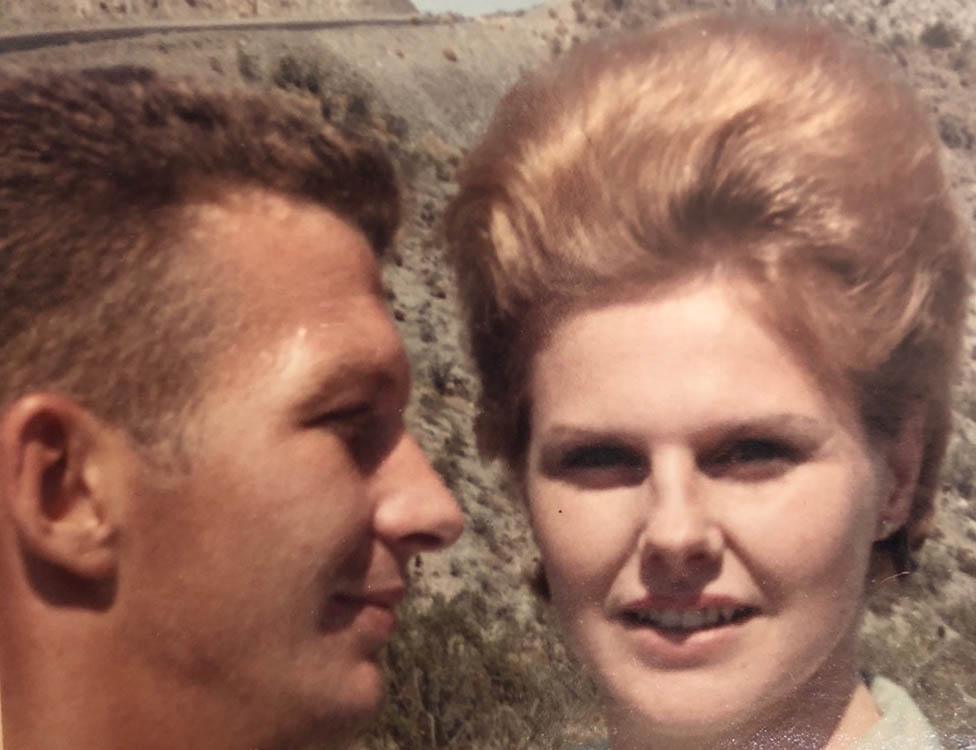

I've known for some time that 23-year-old Sgt Paul Meyer called his wife from the cockpit of his stolen Hercules aircraft - Jane Goodson, as she's now called, told me this herself when she spoke to me from her home in Virginia.

"Honey!" he had told her triumphantly, waking her from a deep sleep. "I got a bird in the sky and I'm coming home!"

What I didn't realise then, however, was that the last 20 minutes or so of their conversation was recorded. And when the transcript of that recording was sent to me, I will admit that I sat down and wept.

By the time the tape recorder was rolling, Meyer's jubilation and bravado had left him. The cold reality of what he'd just done - and what lay ahead - had hit him squarely.

The last conversation between the homesick mechanic and his wife, read by actors - from PM on BBC Radio 4

"Well, honey I'll be really honest with you," he admits. "I kind of think I made a big dang wrong mistake here. I feel like the biggest dodo around here right now. Over."

Jane, clearly petrified, has to still her own nerves as she tries to reassure her panicking husband.

"You are the most wonderful thing in this whole world, you hear?" she says. "Honey, I'm going to bring you home, I'm going to fly you right in here, OK? Over."

Then Meyer's commanding officer tries to cut across the line. "Sgt Meyer! Sgt Meyer! This is Col Kingery, do you read me?" he says. "It's Col Kingery from Mildenhall. Over!"

Alone in the 37-tonne, four-engine transport plane he was not qualified to fly, Meyer - unsure of his direction and unsure of what he was doing - tells his wife desperately: "Everything will be all worth it if I can just kiss your sweet lips one more time. Over."

And Jane, his wife of just 55 days, promises him: "You'll get to kiss my sweet lips until we are old and grey in the rocking chairs in Missouri. Over."

Twenty minutes later, after Meyer has switched the plane to autopilot, the call cuts off. Meyer's final recorded words are: "I'm doing all right, I'm doing all right, uh."

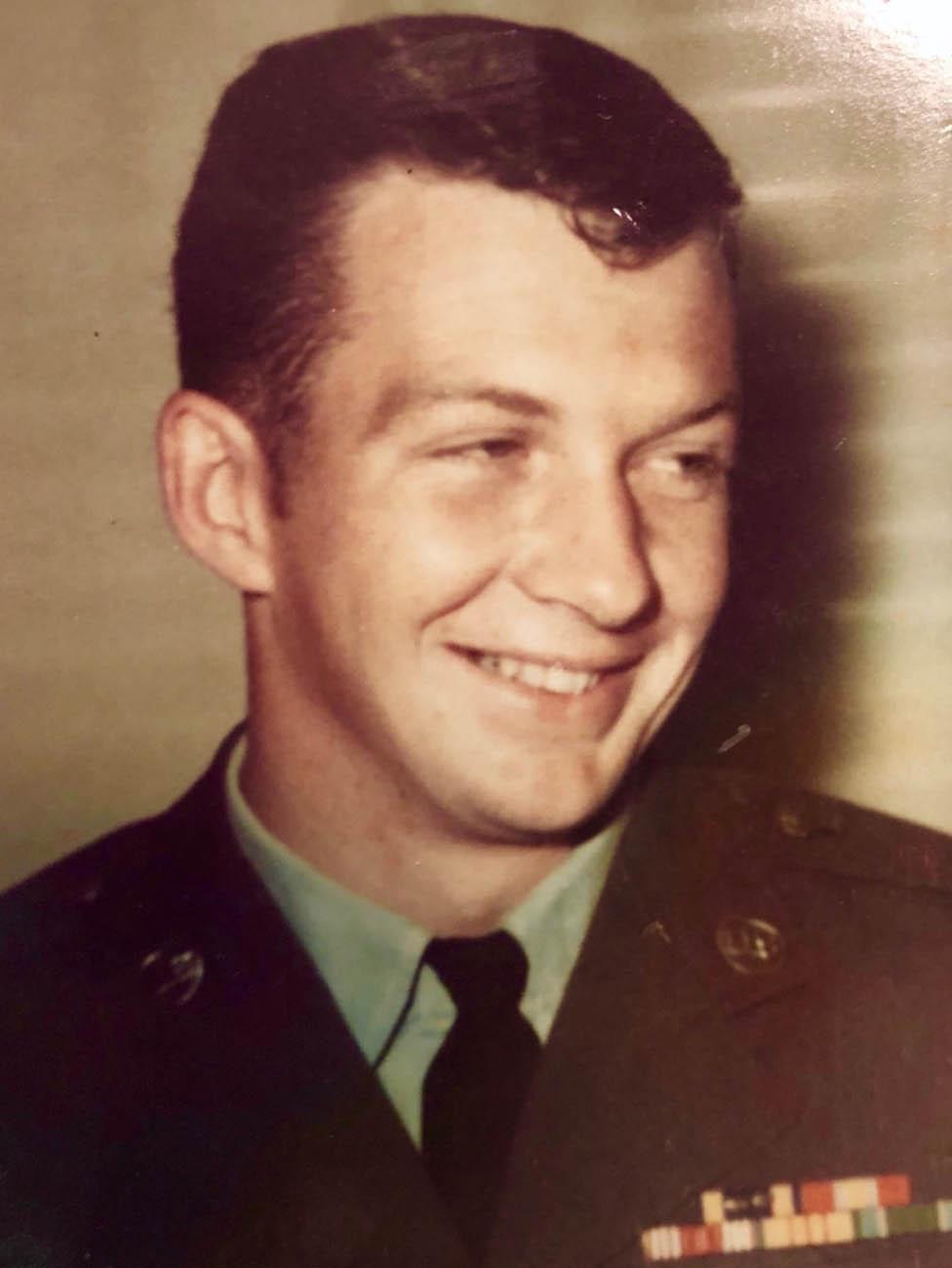

Although he'd passed the USAF's "human reliability test" comfortably in the weeks before being posted to the UK, it's clear that Meyer had not been "doing all right" for some time. A Vietnam veteran, he'd been suffering from flashbacks and nightmares and - homesick and unhappy - he was reportedly drinking heavily.

In 1969, Sgt Ralph Howard Vincent, known by the nickname Sgt Mac, was serving in the 48th Air Police squadron at RAF Lakenheath, a few miles from Meyer's Mildenhall base. The first time he met Paul Meyer in a Suffolk pub, he thinks, Meyer had passed out from the amount of drink he'd consumed. He remembers banging a table to ask Meyer if he and his friends could share it with him, and Meyer, slumped across it, failed to stir.

It was only when the others bought a round that Meyer lifted his head, pushed his empty pint glass towards them and said: "I'll let you sit here if you buy me a drink!"

Sgt Mac spent two long evenings in the pub with Meyer and distinctly recalls Meyer ranting against the USAF, which he said was forcing him to work long hours away from his beloved family. He talked a lot, says Sgt Mac, about his "beautiful wife" and "wonderful step-children" and advised Sgt Mac to settle down and get married too, even though he was only 21. He also offered him some recipes for cooking squirrel. But it was a conversation about flying that really struck Sgt Mac.

"Paul came up with a proposition," he explains. "He said he wanted to get a private pilot's licence so he could fly home on leave… and he wanted to split the cost 50:50 with me… Looking back, I don't think he just got in that plane and took off. I think this was long-planned."

Sgt Mac took a liking to Meyer and made plans to meet him again in the pub. But a few days later, just before breakfast, he remembers hearing a loud roar and his barracks at RAF Lakenheath shaking. He didn't know it then but it was Meyer who'd taken off in the stolen Hercules, on his way home.

In his beautiful Cambridge garden, Vic Blickem shakes his head as he remembers that day. Back then Blickem worked for the USAF at Mildenhall in the casualty assistance office and it was his job to write to his superiors to tell them what had happened, so they could co-ordinate assistance to Meyer's family. He remembers struggling to fill in the paperwork.

"We were totally flummoxed - we didn't know if we should write Missing, Awol, Deserter, or what," he tells me. "So we came up with some form of words or other to get by… We wrote messages, I guess, for a couple of days then we were told not to send any more, and not to ask for updates and we were just shut down. We were shut out. I asked my section commander if he thought Meyer was shot down and he said: 'Well, of course.'"

The US Air Force still has a presence at RAF Mildenhall - it's now home to the 100th Refuelling Wing.

"See that older building there?" asks Dr Robert Mackey, the USAF wing historian, as we wander around the huge base with its lawns shrivelled by the searing summer heat. "That's where Meyer would have eaten his meals." We head towards the shade of a large tree, watching a Hercules thunder overhead. I ask Mackey how the USAF views the Meyer incident today.

"It was a series of bad decisions by people who should have known better," he says firmly. "And now we have systems in place to stop this kind of thing from ever happening again." The facts that Meyer had just come back from Vietnam and was newly married were major stress factors. "The Air Force may not have done what it needed to do to take care of a guy who was clearly in crisis."

Mackey can't pinpoint exactly the location of hard stand 21, from which Meyer taxied up the runway - the base has greatly changed over time and even the control tower is in its third reincarnation since 1969. A young bare-chested airman walks past us in shorts, eating ice cream.

"It was a different time," Mackey says. "Put yourself in the position of those guys - it was 1969, not 1999 - it was the Cold War and you never knew what was going on. Was he stealing the plane? Deserting? Going to East Germany? No-one knew. The system reacted - albeit slower than it could have been. It was a sad incident that resulted in a guy getting killed at the end."

So did the system react by shooting him down?

"No!" retorts Mackey. "No. You've read the transcripts I've read and that is not what happened."

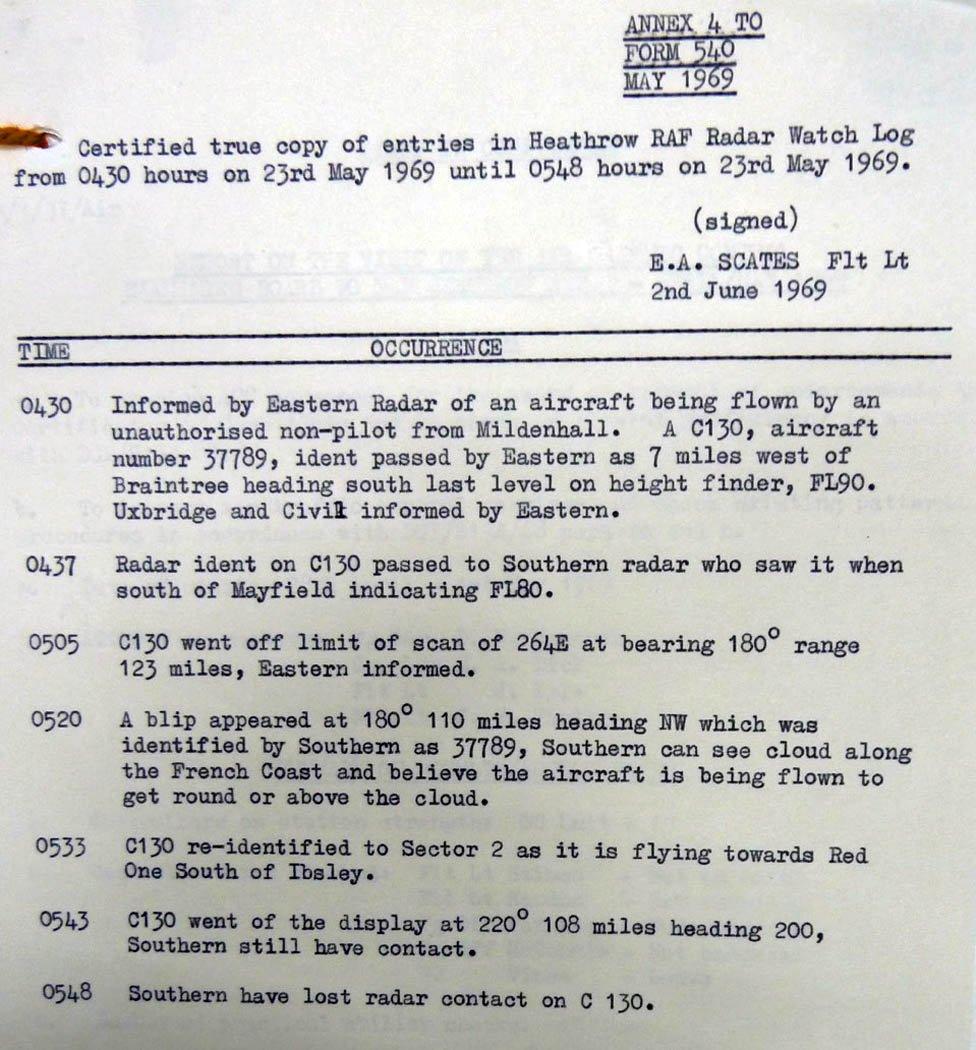

But the transcript of the Mildenhall control tower's conversations with the squadron leader, Col Kingery, various radar posts and the USAF's Central Security Control, don't quite tally with the sparse account in the official USAF official Accident Report (all obtained by Sgt Mac through a freedom of information request, along with the transcript of the conversation between Meyer and his wife).

The accident report claims that only two aircraft - a Hercules from RAF Mildenhall and an F-100 from RAF Lakenheath - were launched to try to find Meyer. Neither visual nor radio contact was established by either aircraft and they both simply returned to base. But the control tower transcript proves that a number of other aircraft took off to intercept Meyer's Hercules. At some point during the search, a British official is recorded telling Col Kingery: "It looks like the French will be sending some fighters up now. This (position) will take him down into the French air which we couldn't really go down into."

And it wasn't just the French who scrambled fighters. In 1969, the east coast of England was peppered with Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) bases ready to respond to Russian threats.

At RAF Wattisham, Peter Nash was a senior aircraftsman with 29 Squadron and he distinctly remembers preparing three Lightning fighter aircraft to scramble.

"A klaxon went off, set off by the aircrew," he recalls. "So we rushed out and got the aircraft ready, the pilots strapped in and quite soon Q1, the primary aircraft, was ordered to scramble. We knew something serious was going up."

Nash shows me photographs of the QRA hangar at Wattisham. He tells me that two of the three aircraft he helped prepare took off, loaded with missiles.

"It was later that morning we heard a USAF guy had stolen an aircraft from Mildenhall," he continues. "And obviously it was our duty as the nearest QRA base to investigate unknown aircraft, so ours were sent to find him, shadow him and, if necessary, to shoot him down."

There is an account of that Wattisham operation in a 2011 book called The Lightning Boys. In it, former RAF pilot Rick Groombridge details how an American exchange pilot took over his aircraft at Wattisham to take part in the Meyer mission and was rumoured to have returned to base minus a missile. Groombridge declined to be interviewed but stands by his story. Nash, however, is adamant that both planes returned to base with all four missiles intact - he should know, he explains, as he was the chief armourer and was responsible for inspecting the weapons and removing the firing plugs.

A few weeks after the incident, Nash was sent on a course where he met a fellow armourer from RAF Chivenor in Devon, who told him that at least one Hawker Hunter was scrambled from his base. Allegedly, the Hunter pilot had returned to Chivenor minus missiles and was met by the RAF police and taken away for a secret debrief along with his plane's camera gun. Nash says he keeps an open mind about the accuracy of the story but observes that Chivenor, being about 150 miles from where Meyer's Hercules went down in the Channel, was about 35 minutes flying time away for a Hunter.

"In other words," Nash says thoughtfully, "it was well within capability."

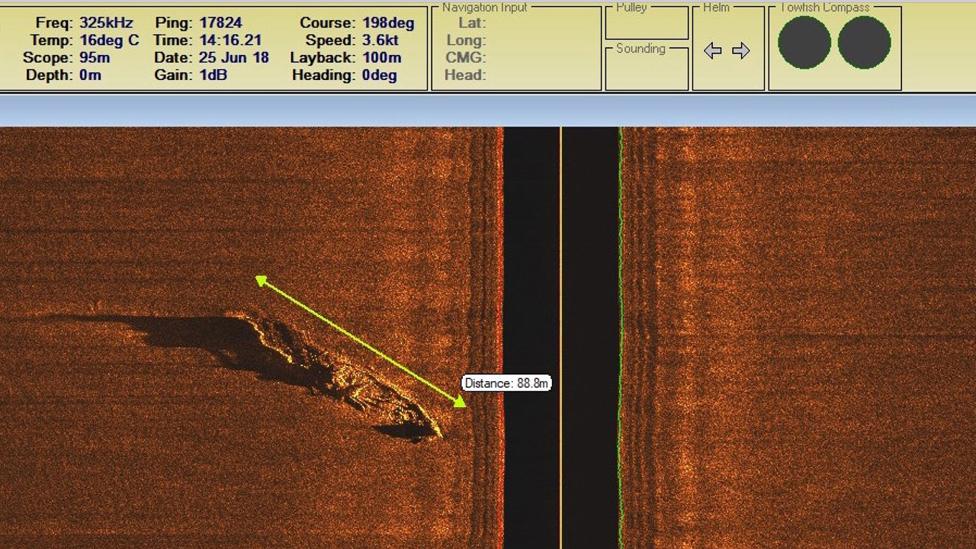

In the Channel's busy shipping lanes, dive boat operator Grahame Knott continues to, as he puts it, "mow the lawn", searching for wreckage of Meyer's Hercules with Deeper Dorset, a team of divers. He's now scoured eight sq miles of seabed, examining targets with a side scanner and using remote cameras to pick up more detail on anything that looks particularly interesting. He's yet to spot anything, although there have been many false alarms. The next step will be to send down divers to look at specific targets. It's painstaking work - getting to this stage has taken 10 years of planning.

A wreck detected on the seabed by Grahame Knott

"Why do I do it?" Knott wonders aloud. "Honestly, I ask myself that all the time and I just keep coming back to the image of young Meyer up there in that plane, completely alone and I guess I'm just doing it for him. He was just a kid, you know?" he says. "Just a homesick kid."

When I first interviewed Meyer's stepson, Henry Ayer, a few months back, he warned me, very gently, to be careful because this story would suck me in. He was just seven when "Daddy Paul" died and he's spent most of his adult life trying to get more information about what caused him to crash. Worn down by conspiracy theories, by conflicting accounts and hearsay, he now just wants to bring Daddy Paul's body home to Virginia.

The official line is that Meyer's body was never found. Yet eight weeks after Meyer's plane crashed into the Channel, two unidentified bodies washed up in Jersey. Detailed contemporary accounts from the Jersey Evening Post tell us that there was great excitement about a male corpse, thought to be aged around 25, found at La Saline Bay, St John's, by a rod fisherman. A subsequent inquest on the body concluded the young man had probably died from drowning. He was never identified although his teeth, which showed dental work of "the British type", were apparently not a match with Meyer's. He was buried in a pauper's grave on the island.

But the newspaper also carried reports about another unidentified body. On 17 July 1969, a launch, the Duchess of Normandy, was sailing back from Carteret in France with several dignitaries on board, when the skipper, Doug Park, spotted a badly decomposed, headless body floating in the water. He wanted to bring the body aboard but was asked not to because of the poor state the corpse was in.

His great friend, Ian Moignard, remembers Park's anger - and he also remembers Park describing the body.

"Doug Park told me it was in some sort of uniform… I think some kind of boiler suit. I do remember he said he'd written down some markings that were on the uniform - I presume he meant a service number on the lapel. But unfortunately the records at the harbour office have been destroyed or just can't be found."

The official USAF accident report tells us that Meyer had been dressed in plain clothes the previous evening at a house party - he'd borrowed a friend's trousers for the occasion - but just before he stole the plane, the report says, Meyer had changed into flight gear.

Park told Moignard that he'd tied the uniformed body to a buoy and alerted the authorities. But by the time the authorities got there it had become detached and floated away.

The next day, the crew of a pleasure yacht, the Tien-Ho, also spotted the headless corpse but because there were very young children present, the skipper felt unable to haul it aboard. Those children, now long grown up, are currently searching for Tien-Ho's missing log book, in the hope their parents might have written down more details.

So the body floated free and Meyer's family was never told about the sighting.

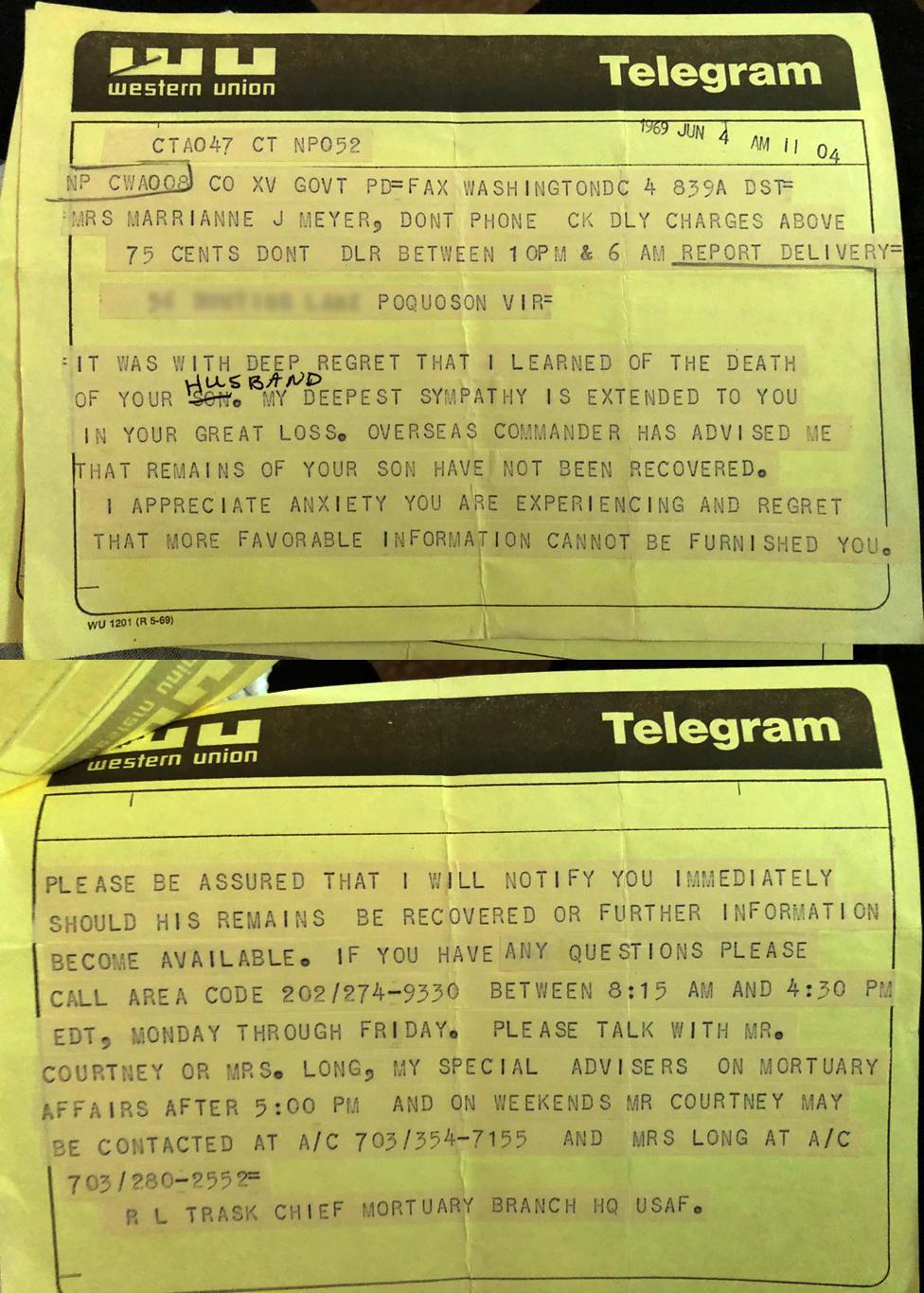

The official telegram Meyer's widow Jane received from Washington, DC three weeks after Meyer disappeared is truly extraordinary.

"It is with deep regret," reads the document, "that I learned of the death of your son." The word "son" has then been crossed out and the word "husband" penned above it. "Overseas Commander has advised me," continues the telegram, "that remains of your son have not been recovered."

I show it to Vic Blickem as we sip coffee in his sunny garden.

He puts his head in his hands.

"That's just terrible, it's just terrible," he says. "It's either so casual they don't care or so incompetent they are negligent. But how terrible for the family."

He laughs self-consciously.

"You know, we all hoped he'd make it," he says. "We wanted him to make it, to get home and to live happily ever after - we even looked at maps to study islands south of England where we thought he might be able to land."

Sgt Paul Meyer's wife, Jane, hoped against hope for that fairy-tale ending too. The cockpit radio transcript tells us she had put the hot water on, all ready for him when he walked through the door. But the narrative didn't take the course she'd prayed for and it was the USAF chaplain who knocked on the door instead.

Once upon a time there was a young, troubled war veteran who just wanted to go home. We are still working on the end of the story.

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.