'I'm surrounded by people - but I feel so lonely'

- Published

When the BBC launched the Loneliness Experiment on Valentine's Day 2018 a staggering 55,000 people from around the world completed the survey, making it the largest study of loneliness yet. Claudia Hammond, who instigated the project, looks at the findings and spoke to three people about their experiences of loneliness.

"It's like a void, a feeling of emptiness. If you have a good piece of news or a bad piece of news, it's not having that person to tell about it. Lacking those people in your life can be really hard."

Michelle Lloyd is 33 and lives in London. She is friendly and chatty and enjoys her job - she seems to have everything going for her, but she feels lonely. She has lived in a few different cities so her friends are spread around the country and tend to be busy with their children at weekends. She does go for drinks with colleagues after work, but tells me it's the deeper relationships she misses.

"I'm very good at being chatty, I can talk to anyone, but that doesn't mean I'm able to have those lasting relationships with people," says Michelle. "You can be in a group and it can be intimidating because you're conscious of not letting people get to know the 'real you'.

"I would say I've always had an element of feeling lonely. Ever since I was a teenager, I've always felt a little bit different and separate from large groups of friends, but in the last five years it's crept in more."

Michelle has experienced anxiety and depression which she finds can amplify her loneliness because she finds it hard to articulate negative emotions.

"If I'm in a group I often find myself saying 'I'm great' when people ask how I am. It's almost like an out-of-body experience because I can hear myself saying these positive things, when I'm thinking about how I struggled to get out bed yesterday. It's the loneliness of knowing how you feel in your own head and never being able to tell people."

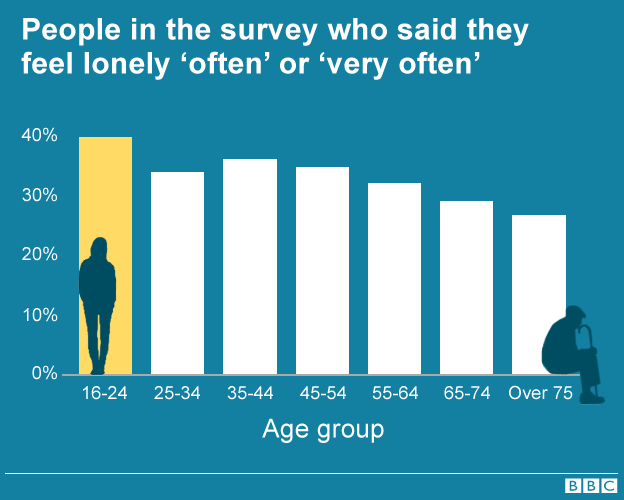

There is a common stereotype that loneliness mainly strikes older, isolated people - and of course it can, and does. But the BBC survey found even higher levels of loneliness among younger people, and this pattern was the same in every country.

The survey was conducted online, which might have deterred some older people, or attracted people who feel lonely. But this is not the first study to see high rates of loneliness reported by young people: research conducted earlier in 2018 by the Office for National Statistics, external on paper as well as online with a smaller, but more representative sample also found more loneliness among the young.

It's tempting to conclude that something about modern life is putting young people at a higher risk of loneliness, but when we asked older people in our survey about the loneliest times in their lives, they also said it was when they were young.

There are several reasons why younger people might feel lonelier. The years between 16 and 24 are often a time of transition where people move home, build their identities and try to find new friends.

Meanwhile, they've not had the chance to experience loneliness as something temporary, useful even, prompting us to find new friends or rekindle old friendships - 41% of people believe that loneliness can sometimes be a positive experience.

Michelle has been open about her loneliness and her mental health, even blogging about them, external. This is not something everyone feels they can do. The survey suggested that younger people felt more able to tell others about their loneliness than older people, but still many young people who feel lonely told us they felt ashamed about it. Were older people afraid to tell us how they really felt or had they found a way of coping?

The BBC loneliness experiment

In February 2018 The BBC Loneliness Experiment was launched on BBC Radio 4 in collaboration with Wellcome Collection. The online survey was created by three leading academics in the field of loneliness research.

The results will be revealed on All in the Mind at 20:00 on Monday 1 October - or catch up via the iPlayer

Listen to The Anatomy of Loneliness on BBC Radio 4

But what the results do suggest is that loneliness matters at all ages.

When loneliness becomes chronic it can have a serious impact on both health and well-being. To try to pin down why some feel so lonely, we looked at the differences between people. Those who told us they always or often felt lonely had lower levels of trust in others.

The survey was a snapshot in time, so we can't tell where this lack of trust in others came from, but there is some evidence from previous research that if people feel chronically lonely they can become more sensitive to rejection. Imagine you start a conversation with someone in a shop and they don't respond - if you're feeling desperately lonely, then you might feel rejected and wonder if it's something about you.

Michelle recognises some of this in herself. "You become quite closed off. You are dealing with so many things alone that when people do take an interest you can be quite defensive sometimes. It can be incredibly debilitating being lonely."

The relationship between loneliness and spending time alone is complex - 83% of people in our study said they like being on their own. A third did say that being alone makes them feel lonely and in some cases isolation is clearly at the root of their loneliness.

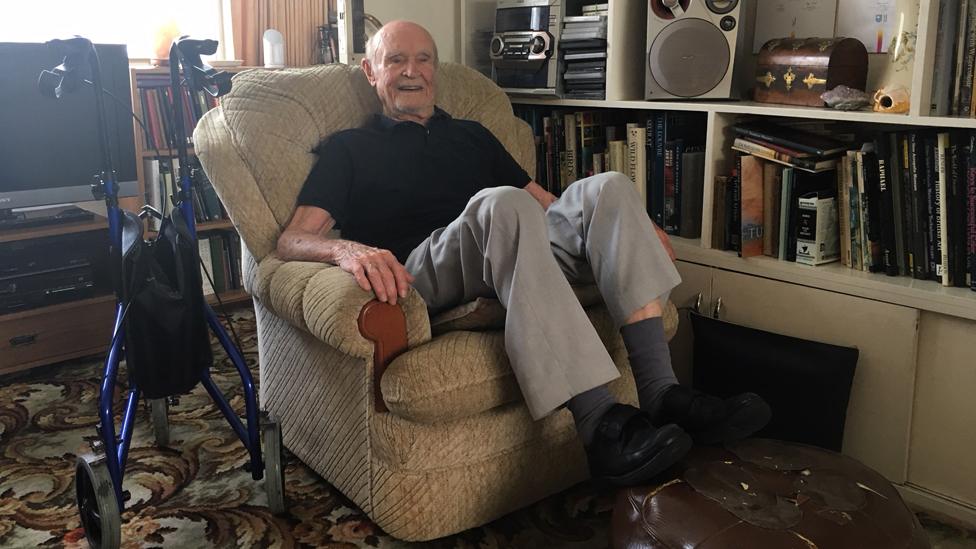

Jack King is 96 and lives alone in Eastbourne, on the south coast of England, after losing his wife in 2010. On his windowsill sits the tennis-ball-sized rock that hit him, leaving a hole in his forehead, when he spent more than three years as a Japanese POW during World War Two.

Today, he says, the days feel very long, but to distract himself from his loneliness he fills his time writing novels and poetry, playing music and painting.

Jack likes to keep busy

"I like to keep busy. I'm creative, it's a curse," he says. It was his creativity which kept him going when he was held captive all those decades ago. He would write comic plays and perform them for the other prisoners, fashioning stage curtains out of rice sacks.

After the war he was on a train which was just pulling out of the station when a young woman on the platform shouted to him that he could take her to the pictures if he liked. At first he thought she didn't mean it, but he did notice her beautiful head of hair. They did go on a date and married the same year. After 65 years of happy marriage she had a stroke, followed by another, developed dementia and eventually died. This is when his feelings of loneliness began.

"Loneliness feels like a deep, deep ache," he says. "It's strange when you find the house empty - you really don't know what to do. We took delight in the simple things in life, like walks. We used to go time after time to watch the cloud shadows on the sea at Seven Sisters. And that's what I miss - that type of companionship that is so close and so intense."

Jack has found some solace in his computer. Now that he's too frail to leave the house very often, he says it's opened up the world.

Too frail to leave the house, Jack finds solace in his computer

When we examined the use of social media in the survey, we found that people who feel lonely use Facebook differently, using it more for entertainment and to connect with people. They have fewer friends who overlap with real life, and more online-only friends. Social media might heighten feelings of loneliness, but it can also help connect people.

Michelle has found it both helps and hinders. "Through blogging, people have been in touch and that's great - but when I am at my lowest, going on Instagram and seeing people having these amazing lives and enjoying themselves does make you feel, 'Why can't I have that?'

"I think it's really important to remember that people only put up the fun stuff," she adds. "I think we should be more honest on social media. Celebrities are trying to be a bit more honest about the less glamorous sides of their lives, but there's a long way to go."

The survey also found that people who feel discriminated against for any reason - like their sexuality or a disability - were more likely to feel lonely.

Megan Paul is 26. Like Jack and Michelle, she's very sociable and lively. She is blind and looks back now on a very lonely time at school, set apart by her disability and even more so by others' reactions to it.

"I went to a mainstream, all-girls secondary school," says Megan. "It was OK for the first couple of years and then when girls hit their teenage years they become interested in makeup, magazines and how boys look - all quite visual things. I loved my books and animals, so I didn't have the same interests. I couldn't talk about whether boys were cute, so there was that natural growing apart."

In lessons pupils would often work in pairs. When the teacher asked the whole class who wanted to work with Megan, there would be an awkward silence until eventually the teacher paired up with her. Sometimes she felt the staff set a bad example.

"I would put my hand up needing help from the teacher and the teacher would ignore me or make inappropriate comments about me. Pupils learn a lot from adult role models at that age and they saw that the teachers didn't know what to do with me," Megan says.

"I felt awful. My mental health was the worst it's ever been. I wanted to die rather than be at school. Then in Year 11 they agreed that I could do a lot of my work at home. I found that was much better than being stressed out at school and it taught me great study skills."

Megan found that her disability set her apart at school

Now Megan is studying for a master's degree and life has become easier, but she says that there are still aspects of her disability which can make her feel lonely.

"As a blind person we can't make eye contact or use body language. If someone who can see comes into a room they will gravitate towards someone who smiles at them. I'm not smiling until I know that they are there, so they don't get any feedback from me.

"The frustration is that I am confident enough to go up to people and chat, but I have to wait for people to come to me. It does mean the friends I have are really special though, because they're the kind of people who persevered. I appreciate the friends I have so much more because I don't have many of them."

When Megan first got an assistance dog, knowing how many people love dogs, she wondered whether the dog might draw people in to talk to her, but she's found that's not always the case.

"Being an assistance dog owner brings its own type of loneliness - a lonely-in-a-crowd scenario," she says. "If people start stroking the dog I'll use that to start a conversation, but quite a lot of people just walk off. Sometimes I feel I'm overshadowed by my dog. I know I'm not cute and furry but I do have something to offer."

I asked Megan whether she has tried joining any clubs or schemes designed to alleviate loneliness. She would like to, but finds access can be a problem. "Meetups are awkward because people don't know how to approach me. I recently tried to join a walking group with my dog, but they wrote back and said I needed to find a group that walks slowly. I'm a fast walker. They should decide how fast we walk together. If I do go to a group, I'm in the corner and everyone swirls around me. But the more groups I could join, the better."

As time goes on Megan has found that one solution is to turn to her phone. "As you grow, you develop coping strategies. If I feel really bad, now I drop people a message. I don't tell them I'm feeling bad, I'm just making connections and reaching out, so I can work through that feeling."

With the high levels of loneliness among young people, a blog Megan wrote, external might be particularly useful for those with disabilities at school today. She includes tips, such as holding the door open for people in order to start a conversation.

"I was so bored at school. A lot of people walked through without noticing, but even if you got a 'Thank you' or a 'Hello' at least it was an interaction. I wasn't able to go up to people and say 'Hi' because I didn't know where they were. So it's one way of getting noticed. It's nice to be seen as helpful rather than 'Here's the weird blind girl again.'"

Another of Megan's tips is to talk to teachers as if they're real people, and not just your teachers.

"Even as a teenager, if you're that lonely you don't care who you talk to. I remember talking to a teacher who told me her cat had had kittens. Afterwards I thought, 'That's one less break time spent alone.'"

Megan says she believes not being able to see has made her kinder to others. "People with vision judge people on appearances and I don't, because I can't."

It's possible that loneliness has made her kinder too. We found that people who say they often feel lonely score higher on average for social empathy. They are better at spotting when someone else is feeling rejected or excluded, probably because they have experienced it themselves.

But when it comes to trust, the findings are very different. Although they may be more understanding of other people's emotional pain, on average people who say they often feel lonely had lower levels of trust in others and higher levels of anxiety, both of which can make it harder to make friends.

Michelle can relate to this. "I sometimes feel that people are just being pitying by wanting to spend time with me. I do have trust issues and I think they stem from my anxiety. I think when you become lonely you do start to look inward and question people's motives. You find yourself wondering whether people spend time with me because they want to, or because they feel guilty."

Sometimes it's suggested that people experiencing loneliness need to learn the social skills that would help them to make friends, but we found that people who felt lonely had social skills that were just as high as everyone else's. So instead, perhaps what's needed are strategies to help deal with the anxiety of meeting new people.

Loneliness around the world

People from 237 different countries, islands and territories took part in the survey

The type of culture you live in has implications for loneliness

People from cultures which tend to put a high value on independence, such as Northern Europe and the US, told us they would be less likely to tell a colleague about their loneliness

In these cultures relationships with partners seemed to be particularly important in the prevention of loneliness

In cultures where extended family is often emphasised, such as Southern Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa, older women in particular were at lower risk of feeling lonely

Both Jack and Michelle find weekends the hardest. Michelle would like to go out for brunch, but has no-one to go with.

"You can do these things on your own, but it's not as fun, because you can't try the other person's food," she says. "Nice weather makes it worse. You see people sitting outside laughing and joking and I think how I want to be part of that.

"If I stay in all weekend cabin fever will set in, so I take myself off to Oxford Street and spend money I don't necessarily have. It's not the most healthy or practical way of dealing with loneliness, but it's about being around people and it's great because you can lose yourself in the crowd."

So what might help? We asked people which solutions to loneliness they had found helpful. At number one was distracting yourself by dedicating time to work, study or hobbies. Next was joining a social club, but this also appeared in the list of the top three unhelpful things that other people suggest. If you feel isolated then joining a club might help, but if you find it hard to trust people, you might still feel lonely in a crowd.

Number three was trying to change your thinking to make it more positive. This is easier said than done, but there are cognitive behavioural strategies which could help people to trust others. For example, if someone snubs you, you might assume it's because they don't like you, but if you ask yourself honestly what evidence you have for that, you might find there isn't any. Instead you can learn to put forward alternative explanations - that they were tired or busy or preoccupied.

The next most common suggestions were to start a conversation with anyone, talk to friends and family about your feelings and to look for the good in every person you meet.

People told us the most unhelpful suggestion that other people make is to go on dates. Michelle says she does feel lonelier now she's not in relationship, but knows that that meeting someone new wouldn't solve everything. "It's important to remember you can be lonely even when you're in a relationship," she says.

Jack and his wife Audrey near their beloved cliffs

Jack still misses his late wife desperately. I asked him whether he would consider sharing a house so that he had company, but he says he's too set in his ways. He wouldn't want to move to a residential home with other older people because then he'd lack the space to paint and write. So, too frail to leave the house, he called the charity The Silver Line, who arranged for a volunteer to phone him every Sunday for a long chat. His three children live a couple of hours away, but they all phone frequently and he has someone who comes in for two hours on weekdays to help out. All of this makes a difference, he says, but he finds it still doesn't give him the companionship he had previously.

"The weekend is a dismal time," says Jack. "The time can drag. I don't have any friends because all my friends are dead. All the ladies I loved are dead. At this age nearly everybody is dead - except me. I'm still here at 96-and-a-half."

I asked Jack what he thinks the solutions are. "Do what you can do. If you're mobile you can join a class or, if not, do something creative on your own. When you're painting simple watercolours you are so intent on what you're doing that you can't think about anything else."

How to feel less lonely

Another of the solutions suggested in the survey was to start conversations with everyone you meet. Jack does that. "It's a polite thing to do," he says. "If you can find an interest that the other person has got, it's a good way to start a conversation."

Several organisations run projects to alleviate loneliness, but Michelle hasn't yet found anywhere she would be comfortable attending.

"Where do you go to find friends if you're 33?" she asks. "People say, 'Get a dog.' I would love it, but it's not fair on the dog at this time in my life. Maybe exercise would be good - joining a yoga class maybe - or volunteering. I know how powerful that can be."

People have told Michelle to "get a dog" to stave off loneliness

But after blogging about her loneliness she might be finding her own solution, tailored to her interest in music. Lots of people have been getting in touch with her about going to gigs and she's thinking about whether she could start some kind of social club in London for other young people who feel lonely and like music.

Michelle has also noticed that the small, kind things people do can help, and she tries to do the same herself. "On the way to work, someone smiling at you on the tube can make such a difference, especially if you've woken up feeling like the world is on your shoulders. I go and get coffee in the building where I work and the lady there is so lovely. That's my first interaction of the day.

"It's just being mindful that everyone is dealing with their own stuff, so be kind. Do tiny acts of kindness."

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.

- Published22 June 2018