Don't shoot, I'm disabled

- Published

Hundreds of people are killed by police in the US each year, and much attention has been paid recently to the high proportion that are black. But there's another disturbing trend that is rarely discussed.

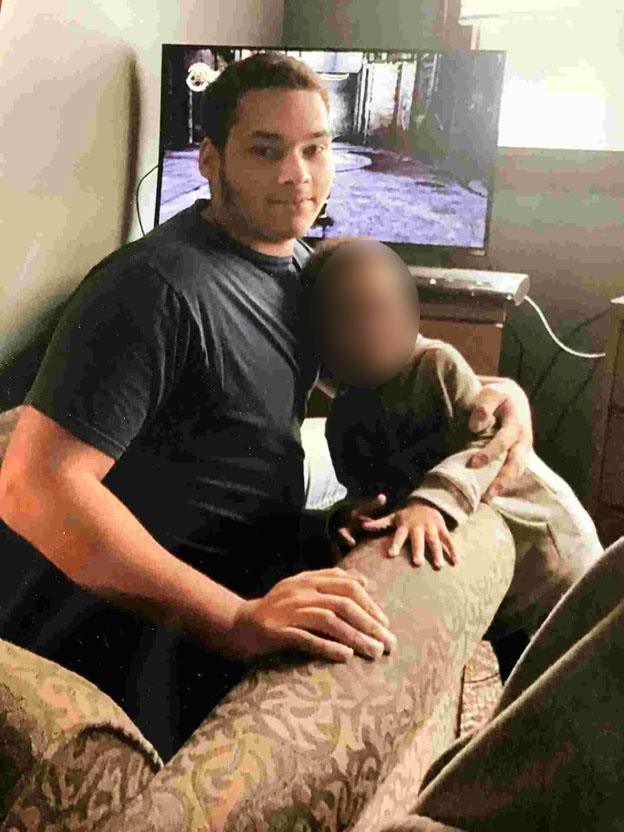

It was shortly after 05:00 when three West Milwaukee police officers broke into the home of 22-year-old Adam Trammell to find him naked and bewildered, standing in his bathtub as water from the shower ran down his body.

Adam, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia, was having some form of breakdown. A neighbour had called 911 to report that she had seen him naked in the corridor, talking about the devil. She thought Adam's name was Brandon, and told police this when they arrived at the building.

According to his father, Larry Trammell, Adam often had delusions and hallucinations. He would take showers to help him calm down when he felt anxious.

Adam was not armed and he did not appear to behave in a threatening manner. But he did not leave the shower as the police commanded.

The officers then fired their Tasers at him 15 times, administering long, painful electric shocks as he screamed and writhed in the bathtub.

Then more officers arrived, and after dragging him, still naked, from his apartment, they held him down and he was injected with sedatives - midazolam at first, and then ketamine.

Moments later, Adam stopped breathing. He was taken to hospital and pronounced dead soon after arrival. The date was 25 May 2017.

We know this is how events unfolded because the incident was caught on cameras worn by the officers.

"I could barely stand to watch it," Adam's mother Kathleen says of the footage. "He was being brutally tortured and screaming out in agony and I could feel the pain, almost. It was like a nightmare with my son as the victim."

Adam Trammell

Kathleen is at a loss to explain why the police behaved the way they did.

"He was just in his own place, he was not out on the streets, he didn't have a weapon. He didn't even have any clothes on, in his own shower. Where was the imminent danger? There was none. He didn't deserve it at all," she tells me, wiping tears from her eyes.

Larry thinks his son may have believed the police were a hallucination. The officers who found him in the bathroom addressed him as "Brandon", not "Adam", because this was the name they were given by the neighbour. "By them calling him by a different name, he was thinking, 'This ain't real,'" says Larry.

At one point Adam splashed water at the officers, something Larry says he might have done as a test to find out whether they really existed.

Even the police acknowledge Adam had not committed a crime and was not suspected of committing one. So why did it happen?

Video: Police confront Adam Trammell. Contains disturbing images.

The police say they broke into the apartment solely to help Adam. They say they acted the way they did to restrain him and get him medical care. In spite of the footage, Milwaukee's District Attorney John Chisholm went so far as to rule that "there was no basis to conclusively link Mr Trammell's death to the actions taken by the police officers". No officers were prosecuted.

There was no national media attention and there were no riots or protest marches. Almost unnoticed, Adam became part of a disturbing statistic that is rarely talked about - the high proportion of disabled people among the hundreds who die after interactions with US police each year.

Conservative estimates suggest that about a quarter of those who die in these interactions have a disability - whether mental, intellectual or physical. But other research indicates that the proportion may be far greater.

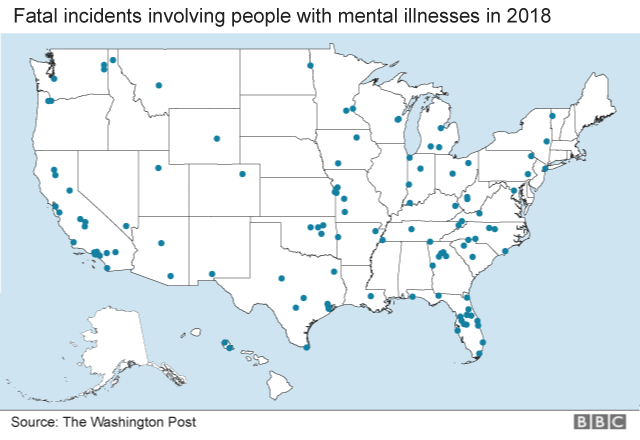

Already in 2018, across the US, at least 136 people with a disability are known to have been killed by police officers, according to a database maintained by the Washington Post and analysis of local media reports.

In many countries the police would be the last resort when people are going through mental health crises but in the US, they are often the first to respond because of the lack of more specialised agencies.

And when I began to look at these interactions between police and disabled people in different parts of the country, clear patterns began to emerge. Adam's story may be extreme, but some aspects of it are repeated time and time again.

Ethan Saylor, 26, had Down's syndrome. On the evening of 12 January 2013, in Frederick County, Maryland, he was at the cinema with his carer, watching the film Zero Dark Thirty.

Ethan Saylor

He was fascinated by its CIA characters and applauded the end of the movie, insisting he did not want to go home. Instead, he wanted to see the film again.

Ethan and his carer left the auditorium but he refused to leave the building. His carer went to bring her car around, hoping this would persuade him, but Ethan went back into the cinema to the same seat in which he'd watched the film.

In the carer's absence, three off-duty police officers who were working as security staff in their spare time heard someone was in the cinema without a ticket for the next showing.

"At some point it becomes, 'You need to leave or you are going to be arrested,'" says Ethan's mother, Patti, who sat through the evidence given in a subsequent investigation.

Ethan apparently told the officers he was a CIA agent and was not going anywhere. "So the officers put their arms under his arms to lift him up and remove him from the theatre," says Patti.

Ethan, crying out for his mother, was restrained and handcuffed.

Find out more

Watch Aleem Maqbool's Our World documentary Don't Shoot, I'm Disabled on the BBC News Channel at 21:30 on 6 and 7 October and on BBC World News at these times

Listen to the documentary on BBC World Service's Assignment

"Somehow in the next seconds or minutes, Ethan ends up on the floor face down and not breathing," Patti says. Attempts to resuscitate him failed.

Initially she thought he had died as a result of some unexplained medical complication.

"I believe it was two weeks later when we were called to the sheriff's department," Patti tells me. "The autopsy report was back and they told us the medical examiner had ruled this a homicide and that he had died of asphyxiation.

"That was the most dramatic and traumatic moment in all of this - realising he had been killed."

Ethan had idolised police officers, even wanting to become one. He frequently called 911 just so he could meet officers and see the squad car pull up to his house.

In the weeks leading up to his death, Patti had visited the local sheriff's office with cookies to thank the deputies for being so patient with Ethan. Now he had died in a confrontation with some of the same officers.

"I took a step back and thought about how ridiculous it was for a young man to lose his life over the cost of a movie ticket. There was no reason for that to occur," says Patti.

"What is the state of mind for a law enforcement officer that they would literally intervene physically with someone with Down's syndrome to the point of their death?"

Patti says the attitude among some members of her community, even some close to her, was that Ethan must have done something to deserve what happened to him.

She says both they and the law enforcement community have made the case that Ethan would still be alive if he had just followed instructions.

But therein is precisely the problem - his ability to follow instructions. Ethan, like Adam, did not have this ability.

It is a problem that is even more apparent in the case of Magdiel Sanchez, a 35-year-old man who was confronted by police on the porch of his own home in Oklahoma City on 19 September 2017.

Magdiel Sanchez

Police believed he was carrying a weapon - it emerged that it was a section of piping - and shouted instructions at him to drop it, but he did not. The confrontation ended with him being shot dead on his front lawn in front of several of his neighbours.

Tragically, Magdiel never heard the police commands - because he was deaf. During the stand-off, neighbours shouted to the officers to tell them this, but they shot him anyway.

Surveillance footage from the house across the street shows that at one point Magdiel, holding the pipe, did run towards officers. He then walked away again and moments later, out of view of the cameras, he was killed.

"He was a special needs child and he was deaf and he was real timid. He was an older boy but he was like a child," says Regina Smith, who saw the end of the incident from her kitchen window.

"I realised it was him and I thought: 'What could he have done?'"

In fact, police only went to his house because they suspected his father had been involved in a hit-and-run incident, and once there they saw him walking around with the pipe.

As I stand outside Magdiel's home, I see one of the neighbours, Kevin Tillery, riding along the street on his bicycle, holding a piece of wood.

Tillery says he always carries it for protection against stray dogs and that at a certain point Magdiel decided to copy him. "He would see me going up and down the street with the stick and one morning he held a stick up (to me) and smiled," Tillery tells me.

Kevin Tillery

But Oklahoma City Police Department defends the actions of the officers.

"Nobody disputes neighbours were yelling that he was deaf," says William Citty, Oklahoma City's police chief.

But he adds: "He understood that they were police officers. That's why we wear uniforms."

Police Chief Citty does not accept that Magdiel's deafness and the extent of his learning difficulties mean the officers should have behaved differently. He says his officers feared being hit with the piping and acted in self-defence.

"It's our job to be able to respond to situations in a manner which creates the best outcome," he says.

"That may include the use of lethal force.

"Under the circumstances at that moment, with what they had to work with, it was the best possible outcome."

As in the cases of Adam and Ethan, none of the officers involved have been prosecuted.

Data concerning the number of disabled people who are killed by police in the US is hard to come by. Researchers are left to go through media reports of individual cases from around the country.

The figures are not officially collected at national level. The current estimate of 136 for this year may therefore be a gross underestimate. In hundreds more cases it was never determined whether the person killed had a disability at all. And there may be other cases that are not reported or that the researchers failed to spot.

This was an issue before President Donald Trump was elected. But his administration has signalled that there will be fewer investigations into police departments when things go wrong, arguing that federal oversight of local police departments reduces morale among police officers.

So what of the officers who have taken the life of someone in these circumstances?

One is Sgt Corey Nooner, who told me about the moment near a school, 15 years ago, when he shot and killed a woman who had schizophrenia.

Sgt Corey Nooner: 'I didn't have a choice but to shoot'

"I was forced into a situation where I didn't have any other choice," he says, becoming visibly emotional.

"We were outside the school, she had a knife and she wasn't responding to my instructions," he says.

Nooner says that given the same circumstances today, he would do exactly the same thing. "I have to make sure I go home to my family at night," he says.

But it is clear that the incident had a profound impact on him.

"After the incident was over, I was told that she had a history of mental illness. I didn't know that at the time. I didn't understand what was going on at the time," he says.

He is angered, though, by any suggestion that American police may be too ready to use lethal force.

"Who would welcome that kind of encounter?" he says. "The reality is that no-one wants to be involved in that moment when they have to point to a weapon at another individual and pull the trigger."

So why are so many disabled people killed by the police?

All police in the US are, of course, armed. There is also the very real prospect that they could face criminals who are, too.

Across the US, 40 officers have been shot dead so far this year.

So a large proportion of police training is geared towards the use of firearms and personal protection. But critics say this creates a police culture that is excessively confrontational, particularly in certain types of neighbourhoods.

An area that has seen a spate of disabled people killed in interactions with officers is Chicago's South Side - one of the most heavily policed areas in the US.

The complaint from many there is that officers too often employ a "command and control" style of policing, especially in low-income areas - shouting commands and physically dominating, particularly when someone doesn't immediately comply. This can sometimes, very quickly, lead the police to use guns.

The problem is - as we know from the cases of Adam, Ethan and Magdiel - that there may be reasons why it is harder for some people to comply with commands shouted at them.

Candace Coleman, who has cerebral palsy, is an organiser with Access Living, an advocacy group for people with disabilities. She grew up in the South Side of Chicago and works with people there who are disabled, particularly those diagnosed with schizophrenia and autism.

"If they do encounter police, it's a scary situation," she says, saying any confrontation with a police officer could lead to extreme panic and confusion in those with similar challenges to those of the young people she works with.

"'Who is this person with a gun?'", they might ask themselves, she says. "'Why are the lights flashing?' 'What are these loud sounds?'"

Being ordered to stand in a certain way - for instance, with their hands where they can be seen - or to look an officer in the eye can also be a problem, she says. So can being touched or grabbed by an officer. "If I'm not used to that, then I'm going to respond in a way that would look as if I'm being defiant," she adds.

That all rings true for Larry Trammell, Adam's father.

"There were times when you couldn't touch Adam," Larry says. "He [could get] really withdrawn or get excited, so I always knew when I dealt with Adam, I was to stay back and let him talk.

"If I went in there and just used my authority as a father and said 'You have to do this' - it just didn't work."

Adam Trammell

After weeks of trying, I finally manage to speak to the Milwaukee District Attorney, John Chisholm, who ruled Adam did not die as a result of the actions of the officers who used Tasers on him numerous times.

"They are not doing this because they wanted to harm Adam. It's the exact opposite, right?" says Chisholm.

"Their expressed intent, any number of times, is that they were there to help him. That they wanted to get him out of that situation."

I put it to Chisholm that they had, indeed, been saying that they wanted to help Adam, but they did so as they were issuing electric shocks - that they had their Tasers drawn even before they entered his home, even though he was in a building where others with mental illness lived. And I point out that the officers started Tasering him moments after the encounter started.

"Right, because they had to get him under control, so they could get him some medical attention," the district attorney repeats.

Lawyers for Adam's family highlight many other breaches of police guidelines that, for example, say someone should not be exposed to more than 15 seconds of cumulative electric shocks using a Taser.

They point out the terrible injuries, including broken ribs, that the post-mortem showed Adam had sustained.

The guidelines say that police encountering someone in a mental health crisis should "avoid increasing the subject's agitation or excitement, avoid physical engagement, avoid restraint and attempt to calm down the subject."

And yet the district attorney ruled that the behaviour of the officers had not been negligent or abusive.

"Not based on their training," he says. "The decision that they have to make is - what's the appropriate means to get him under control so that they can get him the medical attention at that point and time?"

Chisholm insists that Adam may have died anyway because of his health crisis - and that the officers' choice was either to do what they did, or do nothing.

"I would have liked it to have gone to trial," says Adam's father, Larry.

"If it had gone to trial and they had found the officers innocent, it still would have been hard, but we didn't even get that."

Police officers are prosecuted in very few cases involving the deaths of disabled people. They are presumed to have acted in good faith and often given legal protection on that basis.

Adam's case illustrates how police in the US are often called on to do a job that trained medical professionals would be far better placed to handle.

William Citty

"Our calls concerning mental health from 2012 to 2016 have more than tripled," says Citty, Oklahoma City's police chief, whose officers shot dead Magdiel Sanchez.

"This society has not effectively dealt with mental health. They haven't provided the dollars for treatment," he says. "Officers are running from call to call to call dealing with this."

So if the police are to be the first to be called, how can things improve?

"I have to tell you, if you don't know someone with Down's syndrome, you are missing out," says Patti Saylor, Ethan's mother, as she trains a group of police officers in how to interact better with disabled people.

She is trying to turn the devastation caused by the death of her son into something positive, using her own horrific personal experience.

"Ethan didn't have the cognitive ability to recognise those officers needed an explanation," she tells the room. "Like, 'Officer it's OK, I'm going to sit in the seat and watch this movie a second time, my mom is on her way, she'll pay for the ticket when she gets here.' He didn't understand he should do that."

Bereaved mother trains law enforcement

Patti tells me that she is sometimes struck by the level of ignorance about disability among officers, but that this simply mirrors the lack of awareness in society as a whole.

"I have been asked questions like 'You mean they are not all the same?' or 'So they are not out to hurt us?'" she says of officers she has trained.

Officers often apologise to her when they hear her story and display some degree of shame about what happened, she says.

But the Frederick County Sheriff's Office, whose deputies were involved in Ethan's death, has not engaged with Patti. It did agree a financial settlement with her but never apologised or admitted any wrongdoing.

Oklahoma City Police may defend the death of Magdiel Sanchez on his front lawn, but it is clear that the department has tried to make changes since the incident - offering more training to officers on how to approach disabled people.

The force deploys these specially trained officers to incidents where their skills will be useful.

One is Sgt Corey Nooner - the same officer who, 15 years ago, says he was forced to shoot and kill a woman with schizophrenia. That experience pushed him to try to understand mental illness better and he underwent a considerable amount of additional training.

I go out on patrol with him as he is dispatched to a home in an affluent neighbourhood in Oklahoma City.

A man has called to say that his wife, who has recently been discharged from a medical facility, is having a manic episode and experiencing paranoia and delusions.

At their home, Nooner patiently listens as the woman talks, visibly distressed, about how she is being watched by government agencies.

Ultimately, though, after she refuses to accompany him to see a psychiatrist and when she tries to dive into her bedroom, he restrains and handcuffs her.

Later, he tells me he had feared she might try to arm herself and that his basic police instincts kicked in.

For many, the nub of the problem is the way police are taught to interact from the very beginning - with so much emphasis on firearms training and personal protection, and relatively little on de-escalating confrontations.

As things stand, the deaths and injuries of people with disabilities at the hands of the police have left some of the people Candace Coleman works with in Chicago's South Side wondering who might be next, she says. Some of them have made pacts never to call the police under any circumstances, she adds, so worried are they that harm could come to them.

Coleman says they've also got together in groups to discuss what they can do to protect themselves in any interactions with the police.

"Extra disability training for police is one thing but is not enough," she says. "We need a cultural shift across the board."

"The way in which they approach situations needs to change. It shouldn't always be that the immediate reaction is to pull out your gun or your Taser or to yell or scream," she adds.

Until that happens, some of the most vulnerable people in US society will be left to work things out for themselves.

Follow Aleem Maqbool on Twitter @AleemMaqbool, external

Additional reporting by Haley Thomas, videos by Pete Murtaugh

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.