Preventable deaths? The story of Grenfell Tower flat 113

- Published

This is the story of one flat on the 14th floor of Grenfell Tower - flat 113 - and the eight people who sheltered there on the night of the fire. The strengths and weaknesses of the London Fire Brigade's response to the huge challenge of Grenfell may help explain why four of the eight survived, writes the BBC's Kate Lamble - and why four of them died.

Some readers will find this story disturbing

"Zainab loved that tower. She loved the flat. She would invite any person to come, just come and have a look at where she lives."

Francis Dean is remembering his friend, Zainab Deen. He got to know her in December 2015, just as she was about to move into Grenfell Tower with her baby son, Jeremiah. She needed a decorator and had heard Francis did painting jobs in his spare time.

As he painted her living room bright red they became close friends. They had a lot in common: they were both from Sierra Leone and knew some of one another's friends. Francis became a regular visitor to the flat on the 14th floor.

"It was immaculate. When you walk on the floor, you forget that you're in the tower, in a council flat. It was so spotless," he says. "She was cleaning every other second."

Zainab Deen

On 13 June 2017, Zainab had a surprise for him.

"That evening she was so happy. And, I'm like, 'Why are you so happy?' And she said to me, 'I've got a job. And next Monday I'm going to start working,' da, da, da. And she started dancing, like oh my goodness."

They stayed up talking about Zainab's future and who would look after Jeremiah once she started work as a waitress. Then Francis went home.

But in the early hours of the morning Zainab called him. The tower was on fire, she said.

He drove straight over, watching the flames in the distance as he approached. It was huge. It had already spread across two sides of the 24-storey block.

"It was horrible, you should hear the noise, the screams, and the fire was out of control. The firefighters cannot fight the fire at this point. This was just after 02:00 when I got there, and I called Zainab, 'Zainab, where are you?' She said, 'I'm up here.' I said, 'What are you doing there? Come down, come down. Come down now!' I was screaming."

Find out more

This story, which looks in detail at the actions of firefighters on the 14th floor of Grenfell Tower, takes about 25 minutes to read

You can also listen online to Flat 113 at Grenfell Tower, which first aired on Archive on 4 on Saturday 23 March

Francis Dean is still recovering from the events of that night. He's still angry, and he's still got questions.

In the meantime, a public inquiry has also been trying to understand what happened to Zainab, Jeremiah and all the other residents of Grenfell Tower.

From May to December last year the inquiry heard from more than 80 firefighters, dozens of residents, the bereaved, and expert witnesses. The transcripts run to thousands of pages.

As the inquiry has focused so far on the events of the night itself, it's the actions of the firefighters and their commanders that have been in the spotlight.

And the 14th floor, Zainab's floor - six flats occupied by 13 people - illustrates many of the things that went wrong.

As one of the lawyers for the bereaved, survivors and residents, put it: "Floor 14 stands as a paradigm of preventable death."

If you took the lift up to the 14th floor on 13 June 2017 and you crossed the lobby to the right of the stairs you'd find the door to Flat 111.

That was the home of 56-year-old Denis Murphy, a painter and decorator who moved to the tower in 1997 to live near his elderly mother.

Flat 112, next door, was the home of the Alhaj Ali brothers, 25-year-old Omar and 23-year-old Mohammed, refugees from Syria. The brothers had a flatmate but on the night of the fire he was working late and was not at home.

If you crossed to the other side of the landing, you'd reach Flat 113. This was the home of Oluwaseun Talabi, his partner, Rosemary Oyewole, and their four-year-old daughter. Rosemary worked as a secondary school science teacher, and Seun - as Rosemary calls him - worked in construction.

Flat 114 was rented by flatmates Robert Schwillens and Alejandro Serrano, but they were both on holiday.

Zainab Deen and Jeremiah - by now two years old - lived in flat 115.

The last flat is number 116, the home of Nida Mangoba and her teenage son. Nida had lived in Grenfell Tower for 33 years, raising all three of her children there. On 13 June Nida's husband, from whom she had separated, was staying over with them.

The residents of the 14th floor weren't close friends, but they did know each other - like most neighbours, greeting one another as they met in the hallways.

Some were worried about safety. Others had been angered by handling of the building's refurbishment between 2012 and 2016. But most, like Zainab, were happy living at Grenfell.

The first 999 call was made at 00:54 in the morning of 14 June. The caller - Behailu Kebede, had discovered a fire in the kitchen of his flat, number 16, on the fourth floor.

The fire brigade's first engines arrived at 01:00.

On the 14th floor, in flat 112, Omar Alhaj Ali heard them pull up. He and his brother had been visiting friends for their Iftar meal and hadn't got back to their flat until late in the evening.

Ten minutes later, Omar heard shouting. His brother Mohammed came to his room and said he could smell smoke.

The brothers looked out of their lounge window. On the east side of the building there were flames.

"I saw parts of the tower were falling, and the fire was spreading very quickly to the top and I saw the firefighter - he was on the crane just trying to put the water everywhere, down, right, left, everywhere," Omar told the inquiry.

A hose was in use soon after 01:15

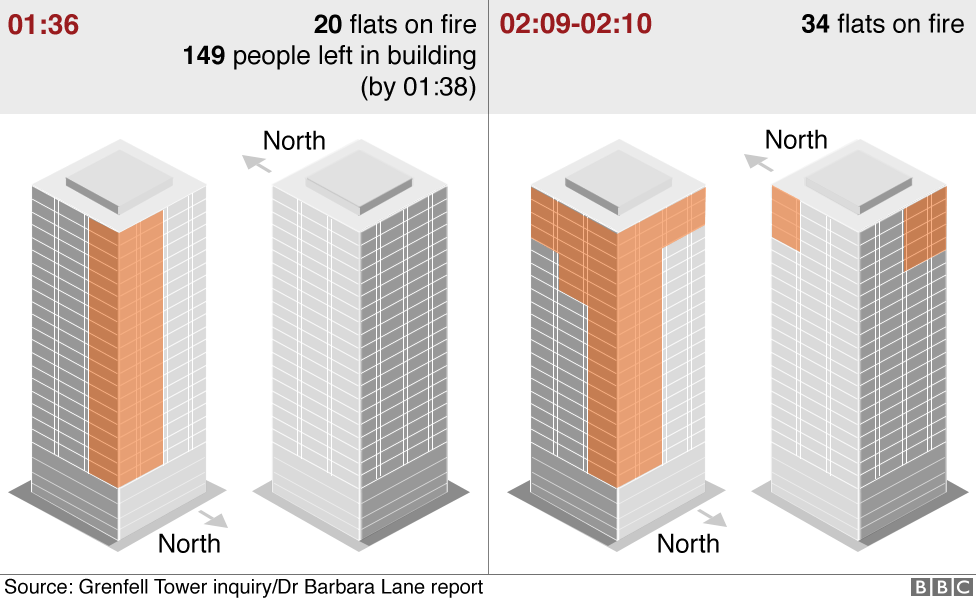

It had begun as an ordinary house fire but only 20 minutes after the first 999 call, flames were rising quickly up the outside wall of the tower block. New cladding, fitted during the building's refurbishment, turned out to be highly flammable.

Once the fire was in the cladding, it moved upwards in a straight line, soon moving beyond the range of the firefighters' hoses, which could only reach as far as the 10th floor.

The building's aluminium and polyethylene rainscreen didn't help. Designed to prevent water entering the cladding, it also repelled water from the firefighters' hoses. But in any case, no firefighter had been trained to recognise and fight a cladding fire on the outside of a high-rise building.

On every floor of the tower, the flat on the north-east corner, with a number ending in six, was the first to be affected. On the 14th floor it was flat number 116, the home of Nida Mangoba. In the early hours of 14 June, she was woken by the sound of an alarm.

"I could see orange and yellow flames shooting up the outside of the tower," she said in a written statement to the inquiry. "As I went further into my kitchen, there was a loud noise like a pop and the extractor fan and the glass in the window smashed into my kitchen. It just missed me."

She grabbed her family and they ran out of their flat and down the stairs. They made it outside by 01:30. By this time the fire had reached the top of the east side of the tower, 19 storeys above its starting point.

Others on the 14th floor started calling the emergency services. At 01:25 Denis Murphy in Flat 111 dialled 999, saying he could smell smoke.

The operator told him that if he wanted to leave he could, but as there was no smoke inside his flat he'd be safer staying where he was. She'd let fire crews know about him, she said.

Grenfell was built on the principle of compartmentation - if there was a fire in one flat, it shouldn't have been able to break out and spread to another for an hour. Compartmentation should have given the fire service time to put out the fire, or reach other residents before they were affected. We now know that at Grenfell compartmentation failed 30 minutes after the first 999 call. But, despite this, the firefighting approach was not changed.

Not everyone on the 14th floor called 999. Omar Alhaj Ali, who was watching the fire from flat 112, shouted out of his window to firefighters on the ground. They told him to stay where he was.

"When you heard that - being told to stay in your flat - did that affect what you decided to do?" Bilal Rawat, counsel to the inquiry, asked him.

"I felt much better, I felt that they would be coming," he replied.

At about 01:30, in flat 113 on the opposite corner of the tower from where the fire started, Oluwaseun Talabi was woken by the sound of shouting. He looked out of his kitchen window. Then he and his partner, Rosemary Oyewole, opened their front door. Outside in the lobby there was thick, acrid smoke.

"It was very hot. it was choking, in that small space there was smoke everywhere, you can't see," Oluwaseun told the inquiry.

"It wasn't like smoke from cooking, [it was] like there was something serious happening. You can't take that risk of trying to step into it so I shut the door."

Rosemary Oyewole remembered that Oluwaseun opened the door again and walked into the lobby to see if he could make it to the staircase - but he was forced back.

"From then I knew there was no escape route that made sense," she said.

Smoke like this, containing toxic gases such as carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, began to fill the lobbies on every floor at about 01:30.

"[With] exposure to these asphyxiant gases, people are totally unaware that they're inhaling them, they have no real effect until the point where you suddenly feel dizzy and collapse," said one of the inquiry's expert witnesses, Prof David Purser.

At 01:37, 40 minutes after the first call to the emergency services, Oluwaseun Talabi and Rosemary Oyewole called 999. Smoke was now filling their flat.

"The hallway, the bedroom, just all that area there was smoke, there was thick black smoke coming in through the doorframe and through the letterbox," Rosemary said.

The control room operator said he'd tell fire crews where she was. He advised her to place wet towels around the door to block the smoke.

"I remember putting a blanket at the top, then trying to hold a blanket along the bottom while trying to hold the letterbox, and that one kept dropping and then that one would drop, and then once I'm holding these two I'd see smoke again coming from the top and I'd try and hold the top one, so it was quite hard," she said.

Experts at the inquiry said that while wet towels block irritant particles, they cannot stop toxic gases.

How the fire spread

At 01:38 Zainab Deen dialled 999 from Flat 115. She was distressed.

Control Room Operator Yvonne Adams took the call. From the transcript it seems they were having difficulty hearing or understanding one another, or maybe Zainab was panicking: Yvonne Adams asked for the number of Zainab's flat, and Zainab replied by telling her the number of the floor - 14.

Yvonne Adams duly recorded that someone was trapped in flat 14 of Grenfell Tower.

"I think I got that wrong," she told the inquiry. "I think she was saying something different at the beginning of the call, but… I remember she was really screaming. It was very hard to understand what she was telling me."

It wasn't just the noise and panic that contributed to a shortage of accurate information reaching firefighters on the ground. In the early stages, when residents on the higher floors said they could see fire, operators sometimes didn't believe them, assuming they were mistaking escaping smoke for approaching flames.

Information that residents were trapped on the 14th floor was passed to firefighters at Grenfell Tower at 01:44, but even though Denis Murphy and Rosemary Oyewole had given their flat numbers, these were not recorded.

Neither was information passed on to say how many people were trapped, how old they were, whether there were any children, and whether they would have difficulty escaping unaided.

On the night of Grenfell the fire brigade received more than 300 999 calls. The volume of information overloaded the usual system used to pass details about who was trapped to firefighters on the ground. As well as using the fire brigade radio, they started to improvise with other means of communication, including mobile phones.

From the control room, to the command point near the tower, then to the commanders' bridgehead within the building and on to the firefighters themselves, flat numbers passed, in some cases, through 10 different officers.

By 01:51, two sides of the building were alight. Twenty-five fire engines had been called to the scene.

It was at this point that four firefighters were sent to the 14th floor. They had to wear breathing apparatus - masks, connected to oxygen tanks, which provide clean air for about 30 minutes at rest, and less if firefighters are exerting themselves.

Firefighters Charles Cornelius and Desmond Murphy were sent to flat 111 - the home of Denis Murphy. Nicke Merrion and Harvey Sanders were sent to flat 112, the home of the Alhaj Ali brothers.

No-one was sent to either of the two flats which had children in them.

And none of those being sent to the 14th floor were briefed about the conditions inside.

"At the bridgehead, there was no smoke, it was clear, and as we made our way up the building, from about the fourth floor - light smoke. The fifth floor became [more smoky] - very, very thick acrid smoke. Visibility was reduced to nothing," Desmond Murphy told the inquiry.

As the teams climbed the narrow staircase in the dark, a firefighter collided with Nicke Merrion. It set off his automatic distress signal. He and Harvey Sanders had to return to the bridgehead to get it reset.

Throughout the tower, while some floor numbers were painted inside the staircase, others looked as though they had been scrawled on in felt tip pen, the inquiry heard. During the refurbishment the floor numbers had changed, and some hadn't been updated. As Desmond Murphy and Charles Cornelius journeyed up the tower, they found it difficult to keep track of which floor they were on.

But they finally reached the 14th floor, and flat 111.

"When we found the flat I went down on to one knee to check the number, and forced the door with my shoulder, and as I went in the gentleman was stood just inside the door. He was bent over and coughing, so he was struggling a bit," Desmond Murphy told the inquiry.

As the firefighters stepped out of flat 111 with Denis Murphy, Omar and Mohammed Alhaj Ali opened the door of flat number 112, next door.

"One was very, very calm, the other was quite distressed and upset. He said, 'Please don't leave us.' I could see behind them that [in] their flat was clear, safe air so I suggested that they step back in and keep the door shut, and asked them to take Mr Murphy in with them, close the door and keep it shut. We were going to search the floor and we'd be back for them."

Omar Alhaj Ali said that when they took Denis Murphy in he was already in a bad way.

"He had inhaled lots of smoke and I could see his face as well, he has lots of smoke on his face, and he wasn't breathing very well."

Firefighters Desmond Murphy and Charles Cornelius knocked on the door of flat 113, the home of Oluwaseun Talabi, Rosemary Oyewole and their four-year-old daughter. Thanks to the wet blankets, the firefighters said, the air in their home looked clean.

Continuing to search the flats one by one, the firefighters found flat 114 empty then arrived at Zainab Dean's flat, number 115.

Desmond Murphy giving evidence

"When we went to flat 115 and found the lady with her son, she was very frightened and she said, 'Please don't leave us alone, don't leave, don't leave me on my own,'" Desmond Murphy said. "So I escorted her and her son across the corridor to flat 112."

Flat 116 was also empty. So just after 02:00 in the morning, the firefighters had found all the people on the 14th floor - six adults and two children, some suffering from smoke inhalation.

By this stage firefighters Nicke Merrion and Harvey Sanders had made it back up the stairs. But they didn't think that between the four of them they could get all the residents safely out of the tower.

"It would have been hard enough for anybody to try and get down 14 flights of stairs in the smoke," said Charles Cornelius. "Let alone somebody who had already taken in a fair amount of smoke and wasn't in the best of health. That was why we decided that that wasn't a good course of action at that time."

The team also didn't have any spare breathing apparatus sets that residents could have worn. Since Grenfell, the London Fire Brigade has purchased smoke hoods, to protect people they are trying to rescue.

The firefighters tried to radio down to the bridgehead to tell them what was happening on the 14th floor, but their radios did not work.

"For me it was a big factor," said Charles Cornelius. "It would have given me confidence in what I was telling the people, that we could send another crew of firefighters up, or more crews, multiple crews, with second sets. And that to me would have been a key element in saving them, if you like."

It's not known exactly why the radios failed at Grenfell Tower. Several possible causes have been discussed over the course of the inquiry - the sheer amount of radio traffic, the concrete shell of the tower blocking radio signals and the poor quality of the communication sets used in breathing apparatus.

Running out of air, the firefighters asked Oluwaseun Talabi and Rosemary Oyewole if they would have the other residents in their flat - number 113, at the opposite corner of the tower from where the fire started. They agreed.

The couple remembered Denis Murphy as nervous and quiet. Omar and Mohammed Alhaj Ali paced around the lounge and Zainab Deen put Jeremiah on their bed.

At about 02:18 in the morning the firefighters returned to the bridgehead. All four told the officers running operations what they had done, and said fresh crews should be sent to flat 113 as soon as possible.

At this point 40 fire engines had been called to the scene and firefighters were queuing up to be sent inside the tower. The police had arrived to hold back crowds of people. Those who called 999 were still being told to stay in their flats.

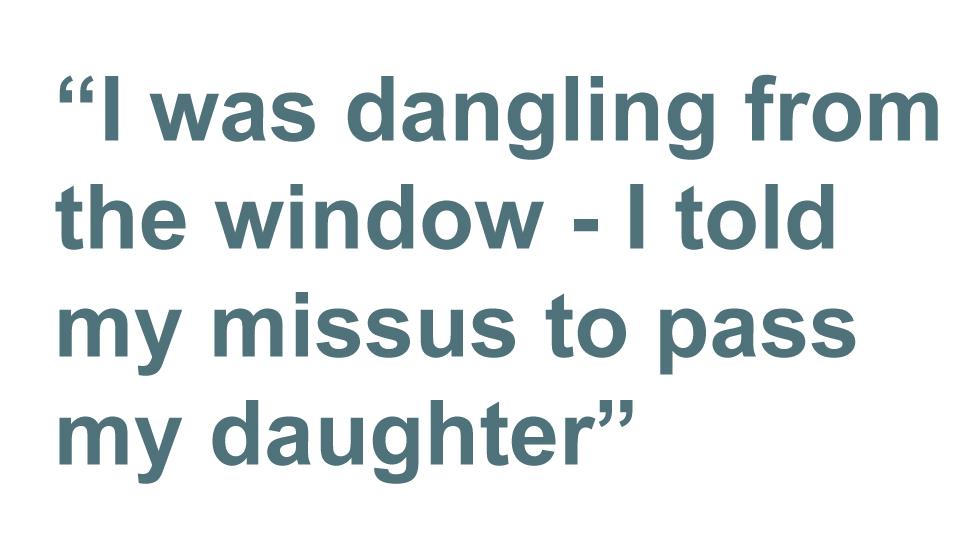

As they waited, Oluwaseun Talabi could see the light of the fire getting brighter and decided to do something drastic.

"Seun had just opened up our airing cupboard and all our blankets or bedding that he could see, I remember just watching him tying sheets together," Rosemary told the inquiry.

Oluwaseun said he even tied pillow cases.

"They had broken off one of the windows, like taken the window off its hinges, so there was a big gap," Rosemary said. "Seun had tied the rope around the middle of the window that holds the two windows… And then he'd thrown it down."

Oluwaseun Talabi's bed-sheet rope spanned 10 floors. To test whether it would take his weight, he lowered himself out of a bedroom window in flat 113. The rope held.

"And I was dangling from the window… I told my missus to pass my daughter and she wouldn't come, she was so scared, she was thinking, 'What are you doing?' And I didn't want to look down because I felt if I looked down I could fall down."

But Rosemary Oyewole was also losing hope that anyone would reach them. When Omar and Mohammed Alhaj Ali pulled Oluwaseun back into the flat, she tied their daughter to his back and they started planning to climb out of the window and lower themselves on the makeshift rope to the point where it stopped, a few storeys from the ground.

But before doing so, at 02:31, they phoned 999 again.

Control room operators reassured all callers that fire crews were coming to get them, whether or not crews had actually set off - this was information they did not possess. But in this case another team had in fact been despatched to flat 113 at 02:26, just a few minutes before.

The four firefighters who had searched the 14th floor half an hour earlier had informed officers that they had moved all the residents into one flat. But the new crew - firefighters Theresa Orchard and Peter Herrera - were not given this information.

In his evidence to the inquiry, Peter Herrera said he was told that "there was a family in flat 113 that needed rescuing". Theresa Orchard, for her part, said she was told there were six people in the flat. Neither knew that in reality there were eight.

Peter Herrera and Theresa Orchard

Another team, crew manager Benjamin McAlonen and firefighter Elliott Juggins, were sent minutes later to flat 111, where Denis Murphy had already been found, and from which he had been moved first into flat 112 and then into flat 113.

Benjamin McAlonen told the inquiry he had not been made aware that other crews had already been to the 14th floor.

He and Elliott Juggins found the door to flat 111 open. They searched it and found it empty. Then they moved to flat 112, the home of the Alhaj Ali brothers, unaware that they too had been moved into flat 113.

That's where McAlonen and Juggins went next, and met the other firefighting team, Peter Herrera and Theresa Orchard, banging on the door. The firefighters told the inquiry that the people inside the flat initially refused to open the door, but the residents denied this.

Their versions of what happened next were also very different.

Peter Herrera said he was eventually let into flat 113 and left his three colleagues waiting outside.

"The approach I took was rapid. I wanted those people out of there quickly because we are in a thick-black-smoke-logged lobby and there's flammable gases, it could go wrong at any time. I just wanted us and the people we were rescuing out of that property as quickly as possible," he said.

He remembered going into the lounge and making sure that the "family" he had been sent to rescue left the flat.

"I pushed them out the door, and handed them over to my colleagues," he said.

So Rosemary Oyewole, Oluwaseun Talabi and their daughter, who was still tied to Olu's back, left the flat. Theresa Orchard described them running past the firefighters outside.

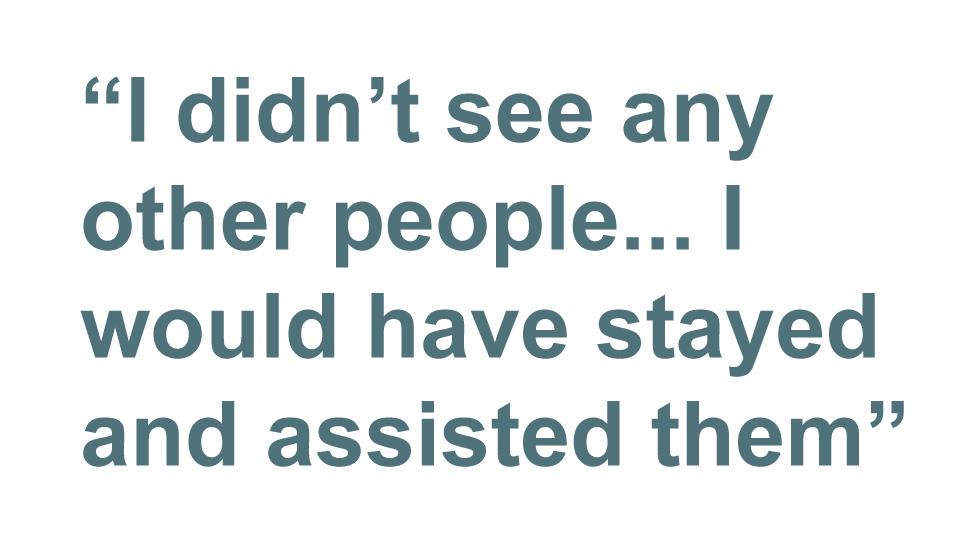

Peter Herrera said he then saw another man standing alone in the lounge - a man who spoke with a Middle Eastern Accent.

"And I asked him, 'Let's go let's go, let's go now. Is this everyone?' And I got a yes," he said.

"I didn't see any other people. If there were other people, obviously I would have stayed and assisted them to leave that property."

Peter Herrera escorted the man out of the flat and, with the other firefighters, began to retrace his steps downstairs.

More on Grenfell

That's the recollection of the firefighters. The evidence given by residents differs in some key respects. They remember all eight people being together in one room.

"The door flew open. I don't know who opened the door. I saw a firefighter standing by the front door and I just heard him shouting," Rosemary said.

"The firefighter basically stood there and said, 'Go.' Meaning, 'Take your chance.' I didn't see him go past... he was still standing there when we left," Oluwaseun said.

They ran out of the flat into thick smoke. Breathing it "felt like I was being strangled", Oluwaseun said. They don't remember any firefighter coming beyond the front door.

Omar Alhaj Ali followed them into the hall, thinking his brother was behind him.

He denied telling Peter Herrera that he was the only person left in the flat.

Omar Alhaj Ali

"I didn't have any conversation, I remember myself being pulled out," he told the inquiry.

What everyone agrees on is that while eight people were inside the flat, only four left.

Asked why firefighters did not conduct a full search of the flat, Peter Herrera said, "I assumed there was no-one in there to search and look for."

Firefighter Elliott Juggins was asked why, having searched the empty flats 111 and 112, he didn't enter 113 and search it too. He said that he and Benjamin McAlonen had been tasked with searching flat 111, while flat 113 had been the other crew's responsibility.

Theresa Orchard, who was dispatched to flat 113 alongside Peter Herrera was asked whether it occurred to her, on the walk down to the bridgehead, why only three adults and one child left the flat, when she had been told there were six people inside.

"It occurred to me. It occurred to me immediately. You know when Pete came out and that was it, it occurred to me. But I don't recall whether I just thought it, or said anything. I don't think I did," she said.

She didn't mention it to anyone at the bridgehead either.

"My assumption was that because three people came out of a smoke-free flat area… that that was all that was in there. They were the only people in there," she said.

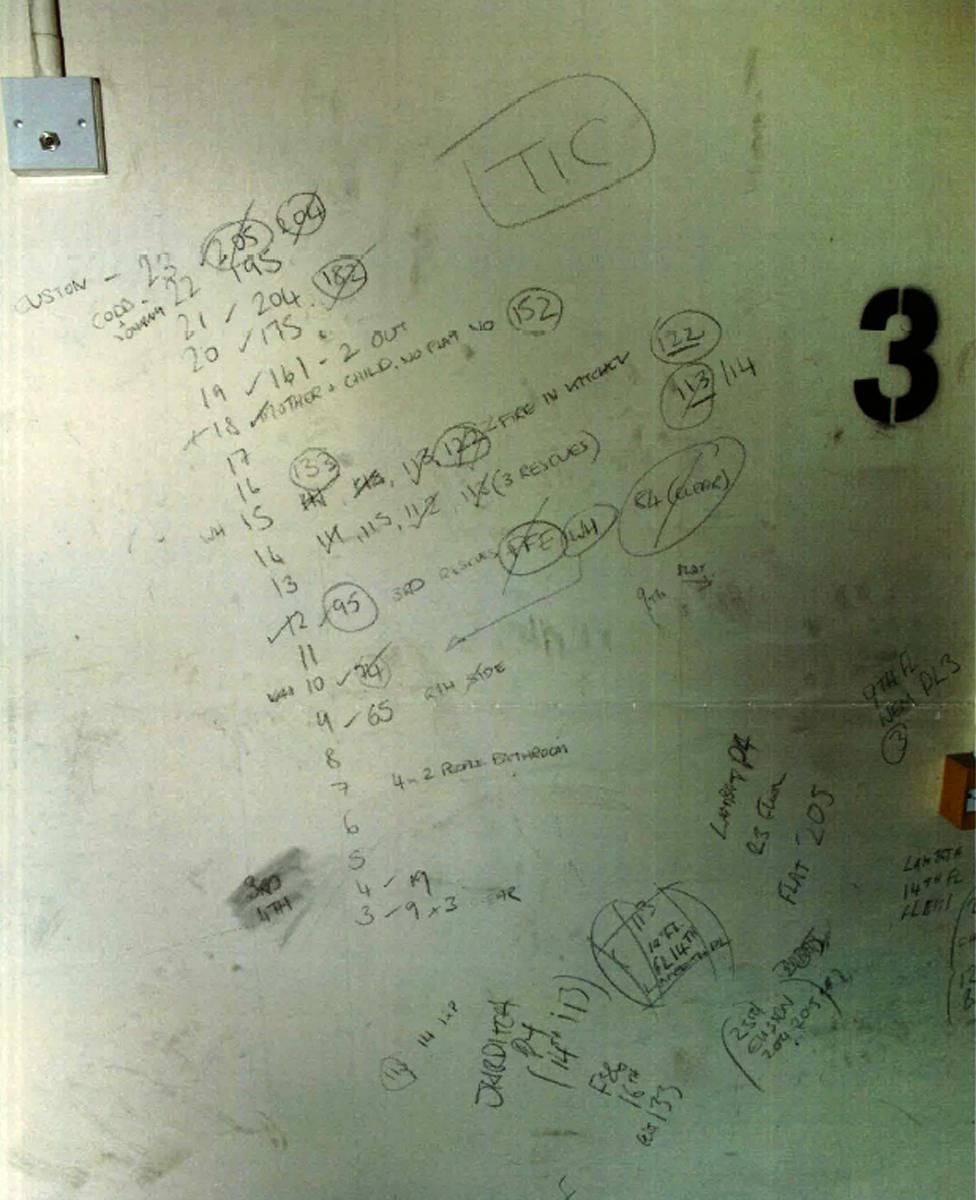

Notes made by firefighters on a wall at the bridgehead record three rescues from flat 113

At the bridgehead Peter Herrera reported back to the officer who had dispatched him and told her flat 113 was empty.

"And did you confirm to the bridgehead that you hadn't carried out a final search of flat 113?" asked counsel to the inquiry, Andrew Kinnier.

"This is the whole thing. We weren't told to go and search these flats, we were told there are people waiting to be rescued and to be assisted down," he answered.

"If you were in that situation behind that door waiting to be assisted down, you'd be ready to go."

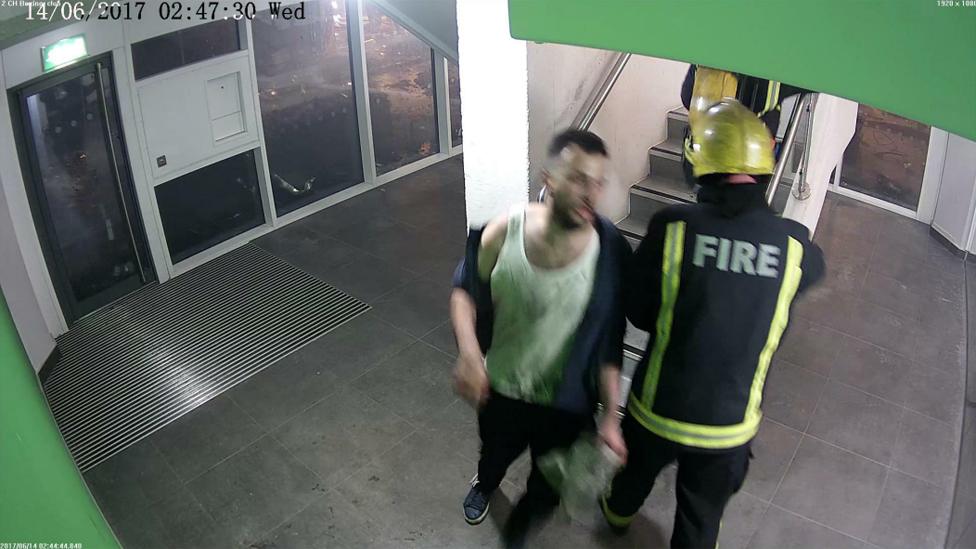

CCTV images show that at about 02:44 in the morning the four residents who had left flat 113 made it to the ground floor.

Rosemary and Oluwaseun's daughter was carried out of the tower by firefighters so she could receive medical attention.

CCTV shows Omar Alhaj Ali leaving the building and talking to firefighters near the exit

Outside the tower, Omar Alhaj Ali realised that his brother Mohammed was not behind him. He phoned him. Mohammed told him he was still in flat 113 with Denis Murphy and Zainab and Jeremiah Deen.

"While I was still on the phone to Mohammed I walked over to a fireman inside the tower and told them my brother was still in the flat and could not get out. I was saying, 'Please go upstairs please there are children upstairs,'" he said in a written statement to the inquiry.

He told Mohammed they were coming for him, but that he should leave the flat if they didn't arrive soon. Mohammed told him the smoke was too thick.

Then Omar found Peter Herrera and told him his brother was still inside, so Peter went back to the tower to speak to Glynn Williams, a firefighter who was gathering information about those trapped in the tower.

"Glynn, 113, there's still a person. I've spoken to the brother, he's on the phone with him, there's a person that's in there that needs to be rescued," he said.

"He told me to put another set on, find someone else, go back up there and get them out."

But being sent into a burning building in breathing apparatus is physically tiring and firefighters are not meant to be deployed repeatedly in quick succession. Guidance says that for their own welfare they should ideally wait an hour before putting on breathing apparatus again. So Peter Herrera did not go back in.

Soon afterwards, at 03:04, Jon Wharnsby and Terry Lowe became the ninth and 10th firefighters to be dispatched to the 14th floor. But on their way to flat 113 the pair met residents trying to escape who needed assistance, so they stopped to help them and did not make it further.

The 10 firefighters sent to the 14th floor

Charles Cornelius and Desmond Murphy - sent to flat 111

Nicke Merrion and Harvey Sanders - sent to flat 112

Theresa Orchard and Peter Herrera - sent to flat 113

Benjamin McAlonen and Elliott Juggins - sent to flat 111

Jon Wharnsby and Terry Lowe - sent to flat 113 but did not arrive

This was a common occurrence. Around 02:40 the 999 control room changed its advice. Instead of telling residents that they would be safer remaining in their flats, they now told them to get out at all costs. This meant many people entered the staircase at the same time, so firefighters sent to particular flats often assisted them rather than completing their mission. As a result, those who were too afraid or unable to make it to the staircase were less likely to be rescued.

By now, Francis Dean, Zainab's friend, had been standing outside the tower for about an hour.

"There was a policeman that came and saw me and said, 'We've got people from the 14th floor.' So at this point I said, 'I'm on the phone to Zainab. She's still on the 14th floor.' I'm like, 'No, no, no, no, she's still up there, she's still up there. They haven't got her out.' So at this point, I decided that I'm going to go into this building and get her out myself."

Francis Dean talking to the BBC a few hours later

Francis tried to run into the burning building through a side entrance, but was turned away by police.

Then he was spotted by a firefighter, Christopher Batcheldor. He checked that fire crews had Zainab's details, before taking Francis's phone so he could talk to her directly.

"He was telling her, 'We're going to come for you. We're going to come and get you. We're coming. Lie down low.' And so he just kept telling her that continuously, you know," Francis Dean remembers.

Christopher Batcheldor talked to Zainab for more than an hour. To begin with he could hear both her and Jeremiah coughing and crying, he told the inquiry. But after about 35 minutes, Zainab told him her son was dead. Beside herself, she told him she no longer wanted to live.

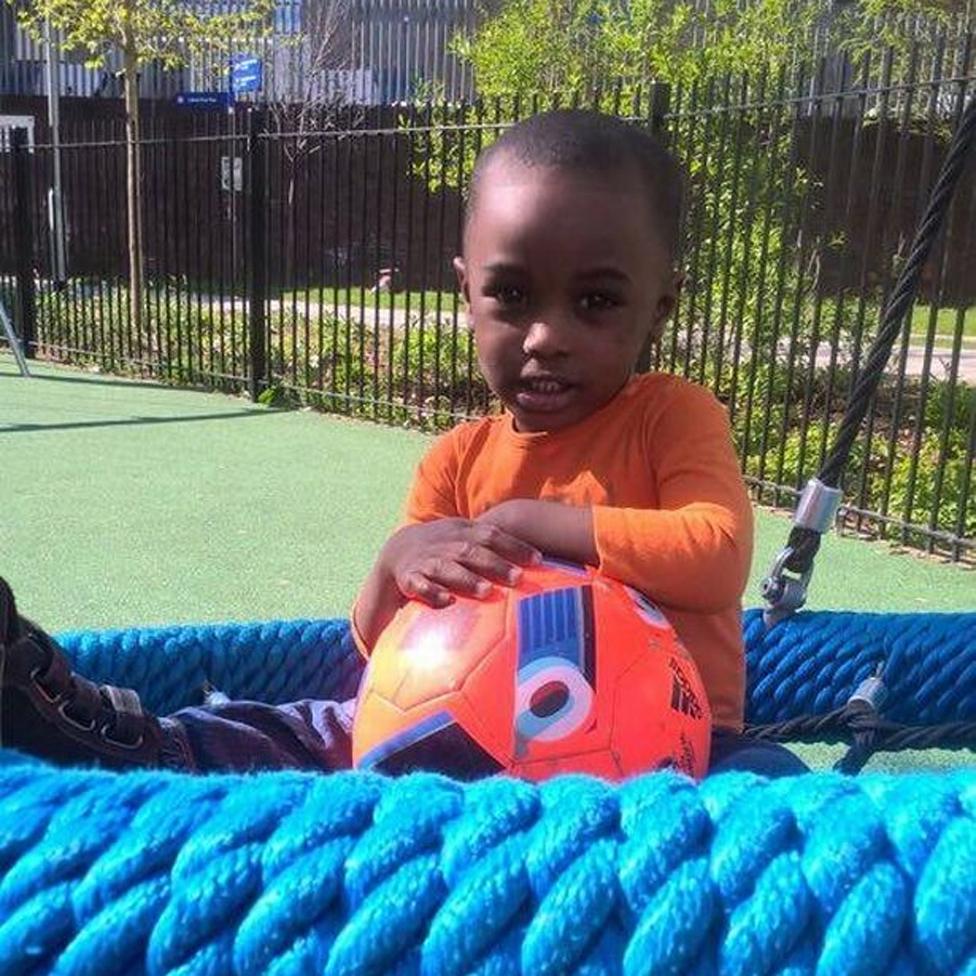

Jeremiah Deen

"It was at that point that I had to try and tell her… 'You ain't giving up on me now, don't talk like that, you carry on fighting,'" he said.

He held the phone briefly to Francis Dean's head, so that he could also urge Zainab not to give up. Then, continuing to talk to Zainab, he walked over to a manager to check that firefighters were on their way to her. But he received devastating news.

"He just looked at me and shook his head and said, 'I'm really sorry Chris, we ain't getting past the 12th at the moment.'"

Christopher Batcheldor kept the call going for another half an hour, until the line went quiet.

He said he told Francis that Zainab's phone battery had run out and showed him to a place where other families were waiting for loved ones.

Throughout these calls neither Francis Dean nor Christopher Batcheldor knew there were other people in the flat with Zainab and Jeremiah.

Omar Alhaj Ali said that after the fire he was told by someone in his family that Mohammed saw the others in the flat die, and then jumped from the tower.

Victim's brother recounts final call: "He said: 'Why did you leave me?'."

Seven people who were on the 14th floor of Grenfell Tower when the fire started survived: Oluwaseun Talabi, Rosemary Oyewole and their four-year-old daughter; Omar Alhaj Ali; and Nida Mangoba, her son and husband.

At the start of the inquiry, the four people who died there were commemorated.

"Denis was a loving son, father, brother, uncle, friend and our hero. He was the lynchpin of our family and touched the lives of so many people," said Anne Marie Murphy, Denis's sister.

A missing poster for Denis Murphy, among others posted on a telephone box

Mohammed Alhaj Ali's fiancee, Amal Al-Huthaifi mourned her partner. "It's really really hard without him. Like even until today it doesn't feel like real that he's not here. Life doesn't taste the same any more without him here," she said.

And from Zainab Deen's father, there was this message: "Until we meet again, beautiful soul, sleep and take your rest. All my love, Dad."

On the night of the fire, the London Fire Brigade carried out at least 65 rescues. But the experience of residents of the 14th floor was typical of many in the tower. The majority of those who died were found in flats on the opposite side of the tower from where the fire started - flats like 113. The longer residents sheltered in a flat that seemed comparatively safe, the longer they were exposed to deadly toxic gases and the more difficult it became for them to leave via the staircase.

Oluwaseun feared he and his family would be killed in the fire

The BBC has put several questions about what happened on the 14th floor to the London Fire Brigade. It said its thoughts will always be with the Grenfell community and that they are "listening, learning and already making changes". But it added that it strongly believed "that drawing conclusions or commenting on the circumstances around specific events on the night, before the public inquiry, police investigation or our own investigations have completed, could be prejudicial to these processes."

During the inquiry, Martin Seaward, the lawyer representing the Fire Brigades Union, had this to say about the "stay put" advice that the fire service issued until about 02:40.

"Some undoubtedly gave the wrong advice and we've listened to the calls and we've read the transcripts and it's undeniable that it doesn't look good in black and white," he said.

"But the FBU asks you, sir, to find that these mistakes were made with the intention of comforting and reassuring and helping, and with the belief that the firefighters would get to rescue people that needed to be rescued and that the firefighters would extinguish the fire. That was the experience of those in control, that's what they expected to happen."

It's worth pointing out that "stay put" is not a fire brigade policy - it's advice based on the design of a building.

The public inquiry's report from its first phase, which will examine what went wrong on the night of the fire, will be released this spring.

The chair of the inquiry will have to consider firefighting policy and equipment, as well as the personal bravery of staff who put their lives on the line to run into an unprecedented fire. Only then will he turn to what may have caused the fire, and investigate the companies and decisions that led to a 24-storey tower being wrapped in combustible cladding - and to the deaths of 72 people.

From what he saw on the night and learned during the inquiry, Francis Dean believes that Zainab and Jeremiah Deen should still be alive.

"I know, yes, it was scary, it was smoky but to know that yes, they did go there to rescue people and not everybody come out is really upsetting," he says.

"And I think the chairman should investigate more as to what really happened on that 14th floor because when you look at all the other floors, the 14th floor more or less stands out, because this firefighter went there so many times and still yet people died."

If you want to find out more about the Grenfell Tower public inquiry you can find all 107 episodes of the Grenfell Tower Inquiry podcast on the BBC website.

See also: Grenfell Tower - who were the victims?

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.