Graffiti punished by reading - 'It worked!' says prosecutor

- Published

In September 2016, an old school house in Virginia, used for teaching black students during the era of segregation, was sprayed with offensive graffiti. The culprits were given an unusual sentence - reading. Two-and-a-half years later, the BBC's Emma Jane Kirby asks whether the punishment worked.

From the moment Prosecutor and Deputy Commonwealth Attorney Alejandra Rueda heard about the racist and anti-Semitic graffiti scrawled across the school house in Ashburn, Loudoun County, Virginia, she suspected the culprits were children.

"The graffiti was racially charged - they had spray-painted swastikas and phrases like 'White Power' and 'Brown Power'," she recalls. "But there were also images of dinosaurs, women's breasts and penises. And I thought, 'This doesn't look like the work of sophisticated KKK people out to intimidate - it looks more like the work of dumb teenagers.'"

Her intuition proved correct. Five children aged 16 and 17 were arrested for the crime and pleaded guilty to one count of destruction of private property and one count of unlawful entry.

The teenagers were unaware of the significance of the building they had defaced. It was the Ashburn Coloured School, an historic building that had been used by black children during segregation in Northern Virginia. The prosecutor believes the children were just kicking out against authority after one of them had been expelled from his school, but she understands why the town was so shocked by the crime.

"The community blew up. Understandably. But you know, some of the kids didn't even know what a swastika meant. So I saw a learning opportunity. With children you can either punish or you can rehabilitate and these were kids with no prior record and I thought back to what taught me when I was their age, what opened my eyes to other cultures and religions… and it was reading."

Find out more

You can hear Emma Jane Kirby's report on the World at One, on BBC Radio 4, at 13:00 on Tuesday 16 April

The judge in the case endorsed the prosecutor's order - that the teenagers should be handed down a reading sentence (or "disposition" as a sentence is known in juvenile cases). Alejandra Rueda drew up a list of 35 books and ordered the offenders to choose one title a month for a year and to write an assignment on each of the 12 books they chose.

The titles included Alice Walker's The Color Purple, My name Is Asher Lev by Chaim Potok, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, Cry The Beloved Country by Alan Paton and Khaled Hosseini's The Kite Runner.

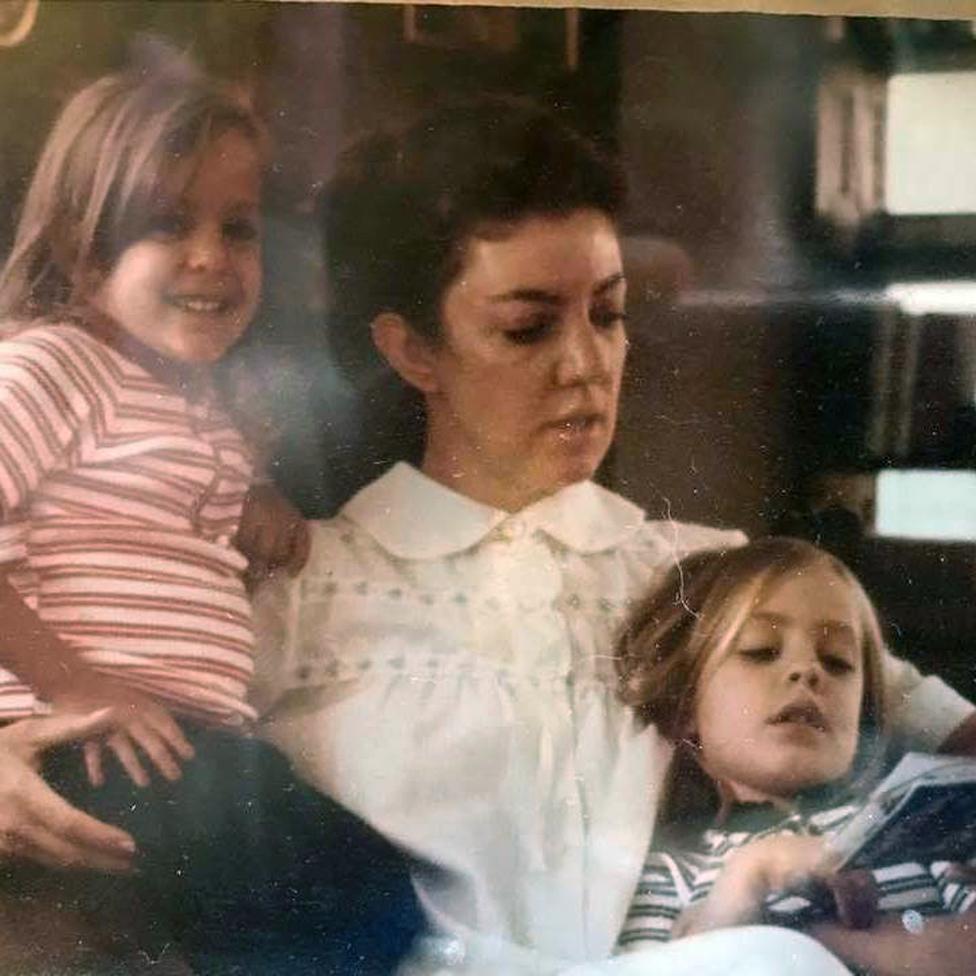

Having grown up in Mexico in a bilingual literary family - her mother was a school librarian - Alejandra Rueda says she owes her own cultural and racial awareness to certain books her mother prescribed. Her mother was determined her daughters should know about the Holocaust, racial hatred and the implications of holding prejudice based on race, religion or ethnicity.

Alejandra Rueda (right) reading with her mother and sister as a child

"I had no idea about apartheid in South Africa until I read Alan Paton and that just blew my mind - I had had no education at all about apartheid," she says. "Likewise, I knew nothing about Israel until I read Exodus by Leon Uris. So those books had to go on my reading list and I also added classics everyone should know, like To Kill A Mockingbird."

The judge was widely praised for trying to educate the adolescents out of their offending behaviour, but some members of the black community wrote letters of complaint to local and national newspapers arguing that teenagers of colour would never have been treated so leniently. In fact, while none of the offenders was black, Alejandra Rueda says three were from ethnic minorities.

Twelve of the 35 books

Things Fall Apart - Chinua Achebe

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings - Maya Angelou

The Tortilla Curtain - T C Boyle

The Kite Runner - Khaled Hosseini

To Kill a Mockingbird - Harper Lee

12 Years a Slave - Solomon Northup

The Crucible - Arthur Miller

Cry the Beloved Country - Alan Paton

My Name is Asher Lev - Chaim Potok

Exodus - Leon Uris

The Color Purple - Alice Walker

Night - Elie Wiesel

"And the sentence was in no way lenient," she argues.

"These kids had no prior record so there was no way they were going to get a custodial sentence at a penitentiary.

"The sentence I gave was harsher than what they would normally have received. Normally it would just be probation which would mean checking in with a probation officer once a month and maybe a few hours of community service and writing a letter to say sorry. Here they had to write 12 assignments and a 3,500-word essay on racial hatred and symbols in the context of what they'd done… It was a lot of work."

All five of the teenagers successfully completed their reading and written assignments along with mandatory visits to the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and the Museum of American History's exhibit on Japanese-American internment camps in the US.

Two years later, none has reoffended, and all are still in education. The teenagers' lawyers say their families were "embarrassed" by their "stupid prank" and that the sentence had had its "intended effect".

Volunteers painted over the graffiti nine days later

None of the offenders was willing to give an interview about their experience, but one agreed that the conclusion of his final essay could be shared:

I learned a lot from writing this paper about how things can have an impact on people - I had no idea about how in-depth the darkest parts of human history go. I remember sitting in history class and learning about this kind of stuff in like two days and then moving on the next week and I thought that was that. I never really looked deep into what went on because a bigger part of me really didn't want to know the horrors.

I thought a swastika was just a symbol and it didn't really mean much - not any more. I was wrong and it meant a lot to people who are affected by them. It reminds me of the worst things - losing family members and friends, of the pain of torture, psychological and physical, among that it reminds them how hateful people can be and how the world can be cruel and unfair. Swastikas are also a reminder of oppression, not being heard and being kept down on the ground. Swastikas are also a sign of white power, that their race is above all else, which is not the case.

People should not feel less than what they are and nobody should make them feel that way. I feel especially awful after writing this paper about how I made anybody feel bad. Everybody should be treated with equality, no matter their race or religion or sexual orientation. I will do my best to see to it that I am never this ignorant again.

When she reaches the final sentence, Alejandra Rueda, who has been reading it out to me, suddenly breaks down in tears.

"It makes me cry," she tells me. "But it makes me feel great because he got it! It worked!"

She wipes her eyes on a handkerchief.

"It worked," she says again, emphatically. "And custodial sentences don't work. OK, some kids have to be in detention because they are dangerous to society or to themselves but for the most part, detention can be very traumatic and that is not the purpose of the criminal justice system when it comes to children."

She blows her nose. "Look, I know I don't sound like a prosecutor here but that is not what I aim to do with children which is why I wanted to be as creative as possible with this case."

In fact, Loudoun County has spent the past year overhauling its juvenile justice system.

Fully restored, as part of a project by students at a local private school, the building was opened to the public in 2017

Alejandra Rueda sits on one of the "diversion committees" and hopes that reading and literacy will now be routinely used in the courts of Loudoun County. Her "reading disposition" has already been used in another case when a 13-year-old boy was found guilty of threatening behaviour and racially insulting a black child. He was also sentenced to a reading list, although the titles selected were more appropriate for his age group.

"We have to educate kids out of ignorance," says Alejandra Rueda. "And with children, our focus has to be on rehabilitation and not retribution if we want results."

You may also be interested in:

When Holly Dawson posted a tweet about a benefactor who left two homes to be let cheaply to hard-up people in her village, it went viral. But there were also many cynics who cast doubt on the story. She felt compelled to check it out.

Home tweet home: A heartwarming story that turned out to be true

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.