The 'poetry of concrete' and the tragedy of a broken bridge

- Published

It's one year since part of a motorway bridge outside Genoa collapsed, as cars and lorries sped across it. Dozens fell off the edge, tumbling 45m to the ground below, resulting in 43 deaths. Here, seven of those closely affected tell their stories.

On 13 August 2018, Emmanuel Diaz and his brother Henry drove across the Morandi bridge. Emmanuel was flying to Colombia to study psychology and Henry gave him a lift to the airport.

"When we said goodbye I hugged him very hard, I told him: 'Henry, I love you very much, I am so proud of you.' I felt weird, because I didn't want to let him go, so much so that the last words he told me were: 'Emmanuel, I really have to go.' Now it feels as though his destiny was already written and life allowed us to say goodbye, because that last hug was perhaps the most intense of our lives. I wanted to hug him forever."

By the following morning, Emmanuel had reached Bogotá and was waiting for his connection to Medellín when he saw on the news that, back home in Genoa, the bridge had collapsed.

Emmanuel Diaz

"I immediately felt something was wrong. There's a special connection that exists between brothers. I looked at a picture of my brother Henry and I thought, 'Why do I feel like you are so far away?' I felt he was no longer with me.

"When I got to Medellín, I tried calling him, calling our friends, our mother in Italy, but I felt powerless. I was almost 14,000km away. So I started looking at the news online, looking for updates. We had a yellow car, very distinctive. I started watching a Facebook livestream and I saw the moment they pulled our yellow car out of the rubble. In that moment I understood my brother was dead. I looked at the image of the car and I thought, 'Nobody can have survived in that car, it's not possible.' I fell to the ground, I lost the strength in my legs, I collapsed."

Deputy Prosecutor Paolo D'Ovidio had just come back from his summer holidays and had left his mobile phone at home. He rang his wife to let her know and she told him to switch on the news.

"She said, 'Look, something's happened to the Morandi bridge.' I went online and saw the first pictures. I hurried home to get my phone, then went with the police to the site. We arrived within an hour of the collapse. There were firefighters, police, paramedics and reporters. It was raining.

"I saw so much desperation. I can't pretend it wasn't upsetting. There were people shouting, crying out; dogs searching for bodies, dogs searching for those still living. And there were whole pieces of bridge, whole pieces of road that had fallen on other roads. There were warehouses destroyed by the 50m-60m of road that had fallen. There was a lorry hanging 50m above the ground with the driver trapped inside.

"Straight away it was clear that, as well as rescuing the survivors, there was an immediate need to understand what had happened, and so the investigation began from there."

One of the first eyewitnesses was Davide Capello, who was driving his Volkswagen Tiguan over the bridge. He was half-way across when he heard a dull metallic sound.

"It wasn't a bang, it wasn't an explosion. It seemed like something made of steel had broken. A crack - as if something had split open. For a few seconds I was stunned. I couldn't work out where the sound was coming from. Then I saw that everything ahead of me was starting to collapse. I saw the cars in front of me disappearing and pieces of road falling.

Davide Capello

"I hit the brakes - trying to stop the car before I ran out of road. But I didn't manage to. I felt the road beneath me vanish and my car nosedived into the void. I let go of the steering wheel and put my hands behind my head. I was shouting, 'I'm dead, I'm dead, I'm dead.' It was a very strange feeling - it happened so fast, I didn't have time to be frightened. All I felt was a sense of powerlessness. Waiting for everything to end.

"I was lucky enough to land on a pile of debris. I remember hitting it with the back of the car. There was a loud crash all around me. It was all sound and dust, as if a missile had hit the bridge. I was in the car for around 20 minutes because I was scared to get out, I was stuck. When I finally got out, I looked around me and all I saw was debris, crushed cars, people inside the cars. There was an unreal silence, an unnatural silence. It was like a war scene."

Thirty metres below the bridge, Mimma Certo was in her family's third-floor flat when she too heard a strange metallic sound.

"I was in the shower. I heard this sound like thunder that seemed to go on forever. Like something colliding with iron. And I couldn't work out if it was a lorry that had fallen on the railway. Then I started to hear people rushing into the street and voices shouting.

"I opened the window and I saw all these cars in the river with their headlights still on, and I looked up and saw the stump of the bridge. That's when I froze. I grabbed my bags and shoes and ran. I rang my sister, and I took a photo because it was impossible to explain what had happened. No-one would believe it."

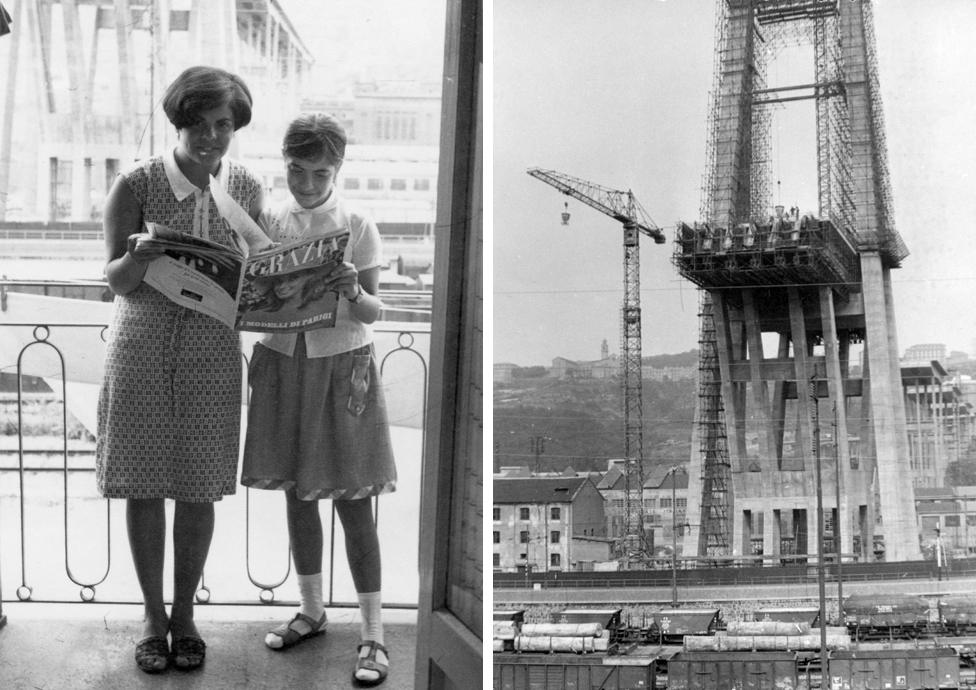

Mimma's sister, Anna Rita, was at work. Now in their 60s, the sisters were children when the bridge was built over the top of their apartment block, back in the 1960s.

"We watched it growing. We played underneath it. When the president came to open it, we felt like we were living under an architectural masterpiece. It was a sign that Italy was growing.

"When I saw the photo of the collapse, I felt like I had been betrayed. Because the bridge was a presence since my childhood. It was like discovering that your best friend is a killer."

Structural engineer Prof Carmelo Gentile was on holiday more than 1,000 miles away in Greece when he received a text from his brother saying the bridge had collapsed.

"My wife told me that I sat in complete silence for 20 minutes after I read that text message. It's hard to describe what was going through my mind," he says.

Carmelo Gentile

The autumn before, Gentile and his team at Milan Polytechnic had tested the bridge in preparation for a €26m project to reinforce the pylon that eventually failed. The reinforcement work had been due to start just a month after the bridge collapsed.

"We use sensors, and from the vibrations we measure variations are detected which give information on the rigidity and health of the bridge. What emerged was that the part of the bridge that later collapsed had very clear anomalies.

"If an engineer sees something out of the ordinary - in this case a waveform that was very strange and outside the usual measurements - you need to run more in-depth tests to open up the structure and go and see what's going on inside. You need to do that as soon as possible."

The Morandi bridge prior to its collapse

Autostrade, the private company that managed the bridge, says it was constantly monitored and subject to frequent routine inspections, and that none of the different types of monitoring ever indicated there was a need for "immediate or urgent intervention."

Gentile sent his report to SPEA engineering, which is a subsidiary of Autostrade's parent company and carries out work for Autostrade.

"If they had asked me to carry out further tests, I would probably have spotted that there was a problem," Gentile says. "Probably as soon as I had fitted the monitoring system, I would have realised the situation had deteriorated since the last tests. In that case, I could have written to a judge and, armed with objective data, requested the closure of the bridge on safety grounds."

Find out more

Deputy Prosecutor Paolo D'Ovidio and his team have gathered evidence which they're presenting to a judge in pre-trial hearings. They're investigating about 80 people, from senior managers to engineers and technicians.

D'Ovidio doesn't go so far as to say Autostrade knew the bridge might collapse, but he does think it's possible there was a "criminal undervaluation of the risk", if not more.

"Our evidence is both the state of the debris and the documents we've seized," he says.

Paolo d'Ovidio

Autostrade says that the bridge was subject to continuous maintenance, as a result of the monitoring that was conducted, and that this work cost €9m in the three years before the bridge collapsed.

But D'Ovidio and his team want to know why the privatised Autostrade waited so long to reinforce the pylon that collapsed. The other two pylons were reinforced in the early 1990s, when Autostrade was still owned by the Italian state. Back then Prof Carmelo Gentile was one of those working on the project and he witnessed some disturbing evidence of decay.

"At a certain point they did an inspection of the bridge and a piece of concrete came away and revealed a hole. Inside you could see the steel falling to pieces. In fact, we found an area where there was no concrete at all. If there is an air pocket inside water gets in and corrodes the metal, making it rusty.

"Riccardo Morandi [the bridge's designer] loved the poetry of concrete so he wanted to make a bridge where concrete was all you saw - the metal was encased in concrete. This design contains a huge number of problems. If everything is done perfectly, you protect the steel inside. But if the manufacturing process is not perfect, you can no longer inspect the steel stay, so you cannot see if there is corrosion or if it has become unsafe. And it was very hard with the technology of the time not to have any air pockets or bubbles in the concrete."

Deputy Prosecutor Paolo D'Ovidio says expert analysis of the debris has shown that, in the section of the bridge that collapsed, much of the metal inside the concrete was also badly corroded. His team are investigating possible manufacturing defects as well as the maintenance and safety checks carried out on the bridge.

"The condition of the bridge was very poor. It was a miracle that it hadn't happened the year before. It could have happened three, five, even 10 years before," he says.

Autostrade has engaged its own experts who dispute that there was evidence of structural fatigue or that the corrosion was sufficient to compromise the load-bearing capacity of the bridge.

"Who's to blame? It's the fault of those who should have got their hands dirty and intervened in the bridge's condition but didn't, those who should have spent the money, but didn't, those who should have checked it, but didn't," D'Ovidio says.

The prosecutors are working towards charging suspects with aggravated or vehicular manslaughter, but it may take years before a court delivers its verdict.

Emmanuel Diaz has put his studies in Colombia on hold so he can fight for justice for his brother, Henry. So far, he's attended every session of the pre-trial hearings.

Part of the bridge is dynamited in June 2019

"That's my job now. That's my life. Thankfully fate kept one of us here on Earth to fight for the other and to take care of our mother.

"Henry and I lived a complicated life. We grew up in Colombia in a world of violence - my father was murdered because he was involved with narco-traffickers.

"When we moved to Italy, Henry and I worked hard to clean up the family name. He was 30 when he died - just a few months away from finishing his degree in engineering. He used to organise charity events to raise money for children in Colombia because so many of his school friends had got lost in the world of narcotics. He always carried a smile with him, because he loved life, he defended it, he glorified it. He said it was a wonderful gift.

"I know there are people who are responsible, I know there are people who must be punished, and I am very confident we will get justice - because that's what Italy wants. What do you do when you are dead? You rise again. Italy will send a message to the world, because Italy wants to return to being the great power it used to be. I know there will be justice for this tragedy."

You may also be interested in:

This is the story of one flat on the 14th floor of Grenfell Tower - flat 113 - and the eight people who sheltered there on the night of the fire. The strengths and weaknesses of the London Fire Brigade's response to the huge challenge of Grenfell may help explain why four of the eight survived, writes the BBC's Kate Lamble - and why four of them died.