The day I met a ‘gay conversion therapist’

- Published

So-called "gay conversion therapy" may be condemned by experts but it is still permitted in the UK. So what happened when gay podcast host James Barr signed up for simulated "treatment"?

I'm sitting in a room in Northern Ireland opposite a man who says he offers "talking therapy" to people who don't want to be gay. And I cannot help feeling worried - despite all the evidence I've read to the contrary, a tiny part of me believes that he may actually convince me that I can choose to stop being gay.

The man in front of me is Mike Davidson, he's originally from New Zealand and he's invited me into his home, about 30 minutes outside Belfast. It's in a very quiet close of small houses tucked away off a side road, the type of place where everyone knows your business. Do his neighbours know what happens here? I start to feel a little uneasy. It reminds me of my home town Eastbourne and of being in the closet, hiding my secrets.

Mike welcomes me via a side door into his tiny office and beams: "This is where we do the work."

It's small but includes a pretty sizable DVD collection. He tells me that he loves movies about war and asks me if I feel the same. I say: "Yes, kind of." We have something in common.

Find out more

James Barr co-hosts the podcast A Gay and a Non-Gay with his (non-gay) friend Dan Hudson (right). The pair travelled to Northern Ireland for From Gay to Non-Gay? - a three-part BBC podcast series in which they meet people who have been through so-called gay "conversion therapy". You can download it here on BBC Sounds.

Mike and I take our seats and it's a pretty tight squeeze. He's a relatively friendly looking man, glasses, a cute face - the sort of person who would help you carry your shopping to the car if he saw you struggling. He seems kind.

He also runs a Christian charity called Core Issues Trust, which, he tells me, "takes people seriously who say they want to move away from homosexual practices and feelings". His technique, he says, is to explore their past experiences and find out more about their unwanted "same-sex attraction".

"What we do is we replace those feelings," he says.

Just under half of those he sees are non-Christians, he says, and he only works with adults.

But despite all the certificates of his achievements at university on his office wall, Mike is not a qualified doctor, and neither is he a registered therapist.

The NHS and all major therapy professional bodies say that what he's doing is unethical and potentially harmful. The UK government has said it wants to ban the practice. However, Mike is still allowed to do it, and here we are.

Mike Davidson

It's been a long time since I had an "unwanted same-sex attraction", as Mike would put it. I'm an out gay man, a comedian, I co-host the UK's biggest LGBTQ+ podcast and regularly chat about sexuality and equality both on TV, on stage and to our international podcast audience - but I remember a moment when a 13-year-old me was less confident.

We're constantly hearing theories as to why LGBTQ+ people exist and at 13, surrounded by straight people, our predominantly heterosexual planet sowed a seed of doubt and shame in my mind about being gay. I realised my life was about to be a lot more difficult as a gay man and, for a split second, I genuinely wished I could've been straight.

Even in 2019, it's actually pretty easy to see why you might want someone to turn you heterosexual. Homophobic hate crimes in the UK are on the rise. Recently, a survey suggested 58% of gay men are scared to hold hands with a partner in public. A lesbian couple were attacked on a London bus in a suspected hate crime which shocked the country.

This is why I am interested in Mike. Is he motivated by homophobia, or does he actually think he's helping people who don't want to be gay? And if he is, is that OK?

And so Mike simulates one of his therapy sessions with me. He asks me if I've had any past trauma.

I reply that when I was younger I was bullied for being ginger, and as I grew older I was bullied for being gay. I tell him about a time when someone kicked me at the bus stop.

Then I ask him if he has a theory as to why that would make me gay.

He replies: "I don't think any one thing gives people same-sex attraction… but if that's your existence at school, it's bullying. And I'm not surprised that maybe you become distant from other males."

His voice is soft, he's sympathetic and for the most part this feels like a normal therapy session, but it isn't. I remind myself that he isn't a real psychotherapist. I know I'm here as a reporter but I'm vulnerable - this is all so personal.

In July 2018, the UK government published an LGBT Action Plan, external in which it says it wants to ban "harmful" gay conversion therapy across the UK. According to a national survey, 2% of British gay people have been through it and 5% have been offered it.

The government says that over half of those that offer this are faith groups - not just Christian - and although Mike operates in Northern Ireland, it happens across the UK.

Before I visit Mike, I meet a young man on the Northern Irish coast called Josh Lyle. He's gay and Christian - his granny used to be a preacher and the church is a huge part of life where he lives. He tells me that in Northern Ireland your religion isn't just a faith, it's part of your identity.

He remembers how one day at his church he walked past a rack of pamphlets. "There was one called 'Bringing your child back to God' and it was essentially a book telling parents how to make their gay children straight."

He's experienced a lot of homophobia. As he walks around town, people regularly shout abuse and he was recently spat at. So he says he understands, in a way, why someone might feel they want to turn to conversion therapy.

"It can be really tough to grow up as a gay kid and if someone came to you when you're feeling at your worst, coming to terms with who you are, and said, 'I have this magic wand that will make you better, do you want me to wave it?' You'd be very tempted to say yes."

However, the consequences of doing so can be extremely harmful. Former Christian singer Vicky Beeching spent most of her life trying to suppress her own attraction to women and tried various forms of gay conversion therapy, from prayer and exorcisms to talking therapy.

One day she noticed strange white patches on her skin. She went to the doctor and she was told she had developed an auto-immune disease called scleroderma.

"The doctors told me my body was at war with itself. They said they believed trauma and stress and specifically my journey with suppressing my sexuality and all the shame around that, they believed that led to all these problems with my immune system," she says.

Vicky sold millions of records worldwide, including her hit, Above All Else, which she says in hindsight perhaps perfectly sums up her willingness to suppress her own sexuality for Jesus's love. She has since written a book explaining why she believes you can be both a Christian and gay.

As I sit opposite Mike, I realise we're mirroring each other's body language. We both have our legs crossed.

I'm curious to find out more about why Mike ended up doing this.

He explains that he grew up in the Church, and when he had homosexual feelings he felt ashamed and wanted to move away from them.

"I always felt other - I always felt different and excluded. I wasn't great at sport." He says he was emotionally disconnected from his father - a war veteran who was great at rugby and cricket. "I said to myself, 'Well if that's being a man,' referring to my father, 'I don't want anything to do with that.'"

For most young men, he says, "it's almost as though they're drawn to the mysteriousness, to the otherness of the female. Now for me, males felt other. Because I didn't feel like one."

He says he went through a form of conversion therapy himself and it helped him realise why he had those feelings.

It's at this point I start to challenge Mike.

I'm more convinced than ever that the reason I'm gay is not because I was bullied - and it's not because I chose to be gay. It's because I was born gay, and no-one needs to explain it or ask why. I just am. I love exactly the same way that everybody else loves.

The NHS and every major therapy body says that efforts to change or alter sexual orientation through psychological therapies are unethical and potentially harmful. Are they all wrong? "If you do research only from one point of view, and you can only get research money if you hold one point of view, then you're going to come up with one point of view," he replies.

But people who come to him are vulnerable, I tell him, and he's misleading them by telling them they can suppress their thoughts.

"I've never used the word 'suppression'," he says. "What I believe in is transformation." He admits he will sometimes see a man and think that he's attractive. "It may be my age, but I don't have that deep longing for an emotional attachment with a man, or a sexual encounter."

Then I ask him: What if it's not true that the feelings gay people have can just be replaced? What if, in fact, he's still gay?

He looks into the distance for a moment, and for a second I wonder if I my words may have changed his thinking. He looks at me and says: "Even if that's right, I have the right and the freedom to identify and to live as I choose."

James Barr in Belfast

Hearing that, I feel sorry for him.

I tell Mike that I think he genuinely does believe he's doing the right thing. I hope that if he were brought up today, in a less homophobic environment, he would be comfortable being who he was.

He offers me a coffee, and I decline. I'd like to leave as soon as possible, but part of me wants to give him a hug. I genuinely feel so sad that someone can be so misled - but I leave. I don't remember if we shake hands, even. In the car, I listen to Gloria Gaynor.

McKrae Game

The founder of one of the US's biggest conversion therapy programmes, McKrae Game, came out as gay earlier this year, and apologised for harming generations of people.

After struggling to suppress his own homosexuality, Game founded his Truth Ministry in 1999, in Spartanburg, South Carolina, rebranding it in 2013 as Hope for Wholeness. The organisation operated in at least 15 states.

"I was a religious zealot that hurt people," he told the Charleston-based Post and Courier newspaper, external.

Seventeen US states have banned gay conversion therapy - most recently Maine, which took the step in May this year.

It's Sunday, and I meet Josh and his granny, Marie Hodgen, outside All Souls Church in Belfast. Josh was scared to come out to his granny, the former preacher. But she more than accepted him. She went back through the Bible and studied its words again.

"When he came out, I couldn't say it was wrong," she tells her grandson. "I love you, Josh. There's no strings attached. I will always love you unconditionally."

Their story overwhelms me.

This is their first time at church together since Josh read that "How to not be gay" pamphlet all those years ago.

As Josh and I walk inside, we both feel anxious. But the minister welcomes both of us. This is an inclusive church that believes in love of all kinds. Josh and his granny cry. I cry.

We sit listening to the minister's words of acceptance. He's telling us that he's excited for his up-and-coming Pride service. Marie looks up and reads out loud a scripture inscribed across the idyllic church's wall: "Sing a new song to the Lord."

You may also be interested in...

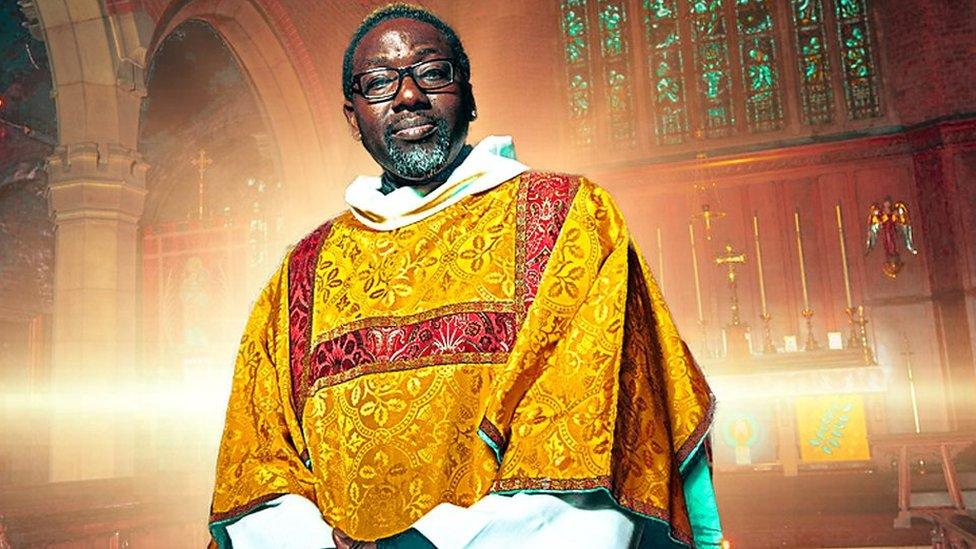

Reverend Jide Macaulay, a Church of England minister, wants to marry his boyfriend. Can he be both a deeply committed Christian and a proudly out gay man?