'I struggled to do my mum justice at her inquest'

- Published

Every year, mental health trusts spend millions of pounds employing lawyers to represent them at inquests, where they could be found to be at fault. The relatives of those who have died, however, often get no legal aid and have to stand up and face those lawyers alone. Becky Montacute describes her bid to ensure that the lessons from her mother's death were learned.

I was at work when I found out that my mum was missing again.

I didn't panic until my brother rang me and said that there were police helicopters over the lake.

Trying to hold it together, I started my journey home to the Chew valley, in Somerset. But in the taxi to Paddington station, I got a phone call from my stepdad to tell me that they'd found a body.

A few days later, I was staring at a leaflet about inquests. I'd picked it up in the waiting room of the mortuary, just after we'd identified my mum's body. With a death like mum's, from the moment it happens the clock is ticking on the legal process, which is your only chance to find out how and why your loved one died. That leaflet - provided by a charity for bereaved families - was the first and last bit of help we received without actively seeking it out. The state offered no support at all.

My mum, Julie, died in the lake on 22 February last year, aged 56.

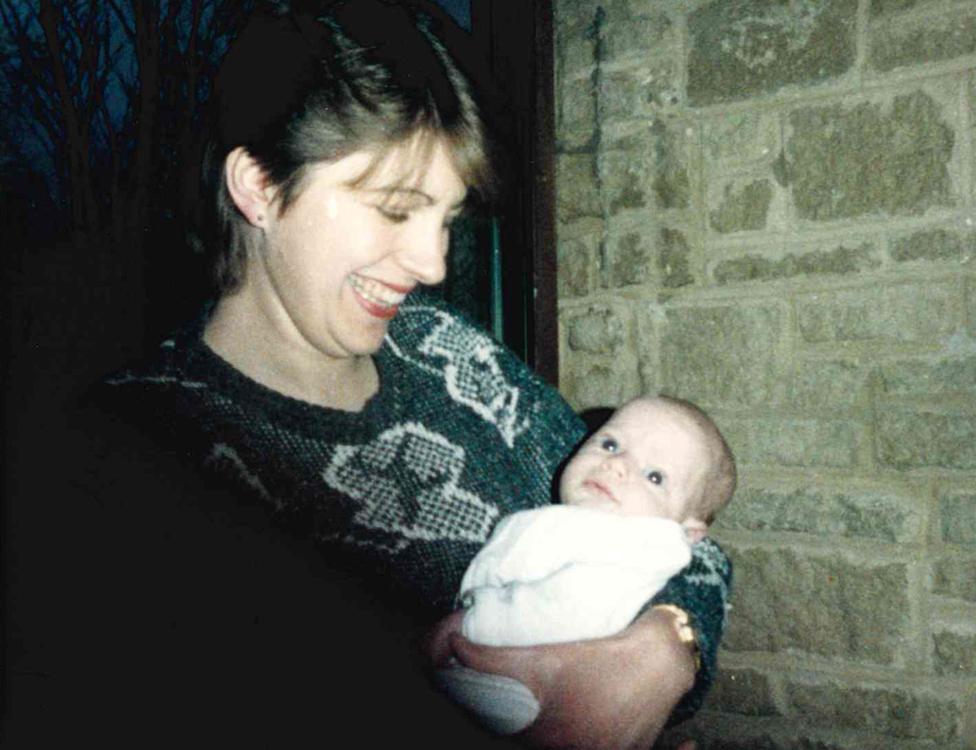

I've since learned that she struggled with her mental health when I was a baby, but I never knew it. She was a wonderful mum, who always put the needs and worries of everyone else above her own. She raised me and my brother on her own for years, and had been looking forward to retiring with my stepdad, and finally being able to relax.

It was clear that mum was seriously unwell when I went home to stay just before starting my first job, in April 2017. She told me then that she had tried to kill herself not long before. After weeks of calls to the mental health team, she was finally sectioned, but she texted me the day she went into hospital to promise she would be out in time for my graduation a few weeks later. Even then, she was thinking about others, not herself.

Becky graduating with a PhD from Manchester University, with Julie

She was sectioned for about six weeks. When she was on the right medication, with someone checking that she actually took it, it was like a switch was turned back on.

But a few months later, at the start of 2018, she started asking mental health services for help again. She was worried her medication had stopped working. She never wanted my brother and me to know how ill she was, and she hid it from us well, but I now know that she was repeatedly calling mental health services. My mum was the perfect patient, actively seeking treatment, but she was not given the care she desperately needed.

Find out more

Listen to Becky's story, Families v the state: An unfair fight? on BBC Sounds

In February, having been seen just once by a mental health nurse, who assessed her as "low risk", mum went missing twice. The second time, she was involved in a serious car crash - so serious that a motorway had to be closed and she was cut out of her car before being taken to hospital.

Miraculously, she was barely injured, but eyewitnesses said that she'd swerved in front of a lorry, and staff in A&E and the police were worried it was a deliberate attempt to hurt herself. Mum was assessed by an emergency mental health team in A&E, but they just sent her home, without providing any guidance on how to care for her. I couldn't believe that after what she had just been through - an experience that would be deeply traumatic even for someone who was normally well - that they could simply let her leave.

Now seriously worried, my stepdad tried hard to get help, repeatedly trying to make appointments with the Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership. After saying for two days that they would see Mum as soon as they could, they eventually offered her an appointment six days later. In desperation, my stepdad got an emergency appointment with her GP, but the GP cancelled it, saying she was the responsibility of the mental health team. She died the next day.

Julie as a teenager

While we can never be sure that she ended up in the lake deliberately, we know she'd attempted suicide before and was just as ill as she had been then. Even though it was clear she urgently needed help, I had never believed that she might die. Nothing can prepare you for that.

For a long time, I was in shock. I went back to work, and I forced myself to see friends, but looking back, I clearly wasn't OK. I often forgot to eat, and was overwhelmed with grief whenever I stopped working for a moment. On top of that, I was trying to care for the rest of my family, including my mum's elderly parents, whose pain I couldn't even imagine.

However, the inquest that was our only chance to find out how mum had come to die was getting closer every day. I was a shocked, grief-stricken 26-year-old, but I soon realised I'd have to get to grips with a complicated legal process I knew nothing about.

Never mind knowing all the answers, I didn't even know what questions I should be asking.

I kept expecting someone from the coroner's office to offer us help, but no-one did. It was explained to me that because of the way my mum had died - in community mental health care rather than while sectioned in hospital - we wouldn't qualify for legal aid. The fact that mental health services had failed to section her when they should have meant that we had fewer rights to assistance. (Even families who do qualify for legal aid, often don't receive enough to cover all their legal bills, and may be left with thousands of pounds to pay out of their own pocket.)

The government says that lawyers shouldn't be needed for an inquest because it's not intended to be adversarial. In other words, an inquest shouldn't involve the kind of arguments that might require a lawyer's assistance. It's meant to be an entirely neutral examination of events, in which all parties are on the same side - seeking the same truth.

Julie and Becky as a baby

But the reality felt very different. At my mum's inquest, as with almost all cases like hers, the mental health trust and the GP involved in her case arrived with legal representation.

I'm lucky. I have friends who are lawyers, and even a friend who works on inquests. They gave me good advice right from the start of the process. Straight away, my friend told me to write down everything that I could remember from the weeks before mum died. I am so glad she told me that, because within days the shock meant I could barely remember that time at all.

My boyfriend also helped me to find the charity, Inquest, which gave me a case worker to ask for advice. In the end, the only lawyer I could find and afford was a friend of a friend, who offered me a massively reduced rate. But even then the cost ran to several thousand pounds for four days in court.

I spent weeks preparing, reading through the pile of medical notes and notes from the mental health trust's own investigation - which the coroner had sent me - to try to figure out what I needed to say and what questions needed to be asked. It was in those notes that I read the official cause of death - drowning - for the first time. No-one had actually told me. I just came across it, without warning, in a pile of documents.

Finally, a few months after mum's death, I stood up in court. For two preliminary hearings I couldn't afford for my lawyer to be present, so I had to represent my mum myself. Speaking in front of the coroner, the lawyers, and my own family was honestly the most terrifying thing I've ever done, and I was desperate to do it well, to do my mum justice.

Legal aid for inquests

On behalf of the foundation set up in her mum's memory, Becky Montacute submitted Freedom of Information requests to the 53 mental health trusts in England, asking how much they'd spent on lawyers at inquests in the financial year 2017-2018. About half of them responded - revealing they'd spent more than £4m. That compares to just under £118,000 (£117,968) made available to families as legal aid for inquests involving mental health trusts.

BBC Radio 4's File on 4 has been told by the Legal Aid Agency that out of more than 600 requests for legal aid for inquests last year, almost half were refused.

Even though he couldn't be there for the preliminary hearings, my lawyer's advice was crucial. The coroner had planned for the inquest to only look at events in the few days after mum's car crash, leading up to her death. The lawyer advised me that I could push for it be extended so that the weeks before that, when she'd been fruitlessly trying to seek help, would be examined as well. Several of the failings that the coroner eventually identified came during that period.

A friend came to court when the verdict was given and wrote down everything that was said. This turned out to be crucial as the court itself will only release a transcript of the inquest for a large fee, and my adrenaline was so high that I honestly wouldn't have been able to remember everything.

For the inquest itself, my lawyer was present and the relief was enormous. Finally I could sit back and really observe what was happening, safe in the knowledge that someone else had taken on the burden of arguing our case. One of his lines of questioning resulted in an emergency witness being called, whose evidence revealed a "gross failure" in mum's care.

By questioning the new witness - a member of the emergency mental health team - the lawyer showed that Mum should have been referred to the emergency team the day before she died, and if she had been, she would have been their top priority. Someone would have been out to see her within an hour. There is no doubt in my mind that had that happened she wouldn't have died.

Of course, an inquest couldn't bring my mum back, and it's difficult to explain why knowing for sure what happened matters so much.

I'm plagued with guilt over whether I could have done more to protect her. I was frustrated with the lack of support from mental health services, but in the depths of grief, you start to doubt yourself. Maybe it was unreasonable for me to think mental health services could have understood how ill she was? They didn't know her the way I did. As her daughter, shouldn't I have known, and then done all I could to save her? I was tormented by the thought that I went back to work when she was so ill.

Understanding what had really happened was vital in order for me to accept that it wasn't my fault.

The second thing I desperately needed was for something good to come out of Mum's death. So much had gone wrong, that I needed to know that systems would change, so that someone else wouldn't die needlessly, and other families wouldn't have to suffer. In the end the inquest did make a huge difference.

In his summing up, the coroner found nine failings in the care my mum received. One - when a mental health nurse, who was meant to be assessing her, failed to ask anything about her mental health and only talked about the car crash - was described as a "gross" failure. The failures taken together also amounted to a gross failure.

Julie and Becky in the garden

I took the coroner's findings to the mental health trust responsible for the hospital that discharged her after the car crash. After seeing the evidence from the inquest, it agreed to make several changes, including changes in staff training and improvements in the exchange of information between A&E and mental health nurses.

The trust that looked after her as a patient, Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health NHS Trust, told the BBC they accepted the coroner's findings and apologised to my family. They also confirmed they had changed their working practices as a result.

It's difficult for me to tell this story, and the experience of the inquest means I've already told it again and again. But I was shocked that my mum could be so badly let down by the mental health services. Before it happened to her, I wouldn't have thought that was possible in this country. I've since found out about numerous similar cases, in our area of the country alone.

It's hard to see how this can improve unless tragedies like my mum's are properly explored, and changes made. But the system seems to be weighted against the bereaved families who have the strongest incentive to ensure that the lessons are learned.

As told to Mary Goodhart

You may also be interested in:

In 2017, music student Jessica Hurst, 25, was told her father had died at the age of 56. Then came the discovery that he had killed himself after getting into debt. As she explains here, it had begun as a relatively small debt for unpaid council tax - but it multiplied many times after the council had him declared bankrupt.