Michael Morpurgo on keeping right on to the end of the road

- Published

Michael Morpurgo, the author and former children's laureate, is 76 on Saturday 5 October 2019, and he's beginning to feel his age. But he's not downhearted, partly because he draws inspiration from others who've stayed active and positive to the end of their lives.

Strange thing, getting old - because I never thought it would happen to me. Well, it has, and quite suddenly too. Life these days is punctuated with little reminders. A certain reluctance, that I never had when I was young, when it comes to looking in the mirror. Full body or face. Neither merits a second glance. Mirrors are in fact a perfect nuisance. In lifts with mirrors all round, sometimes you catch a glimpse of the back of a head that always lacks more hair than last time you looked, less than you had supposed or hoped.

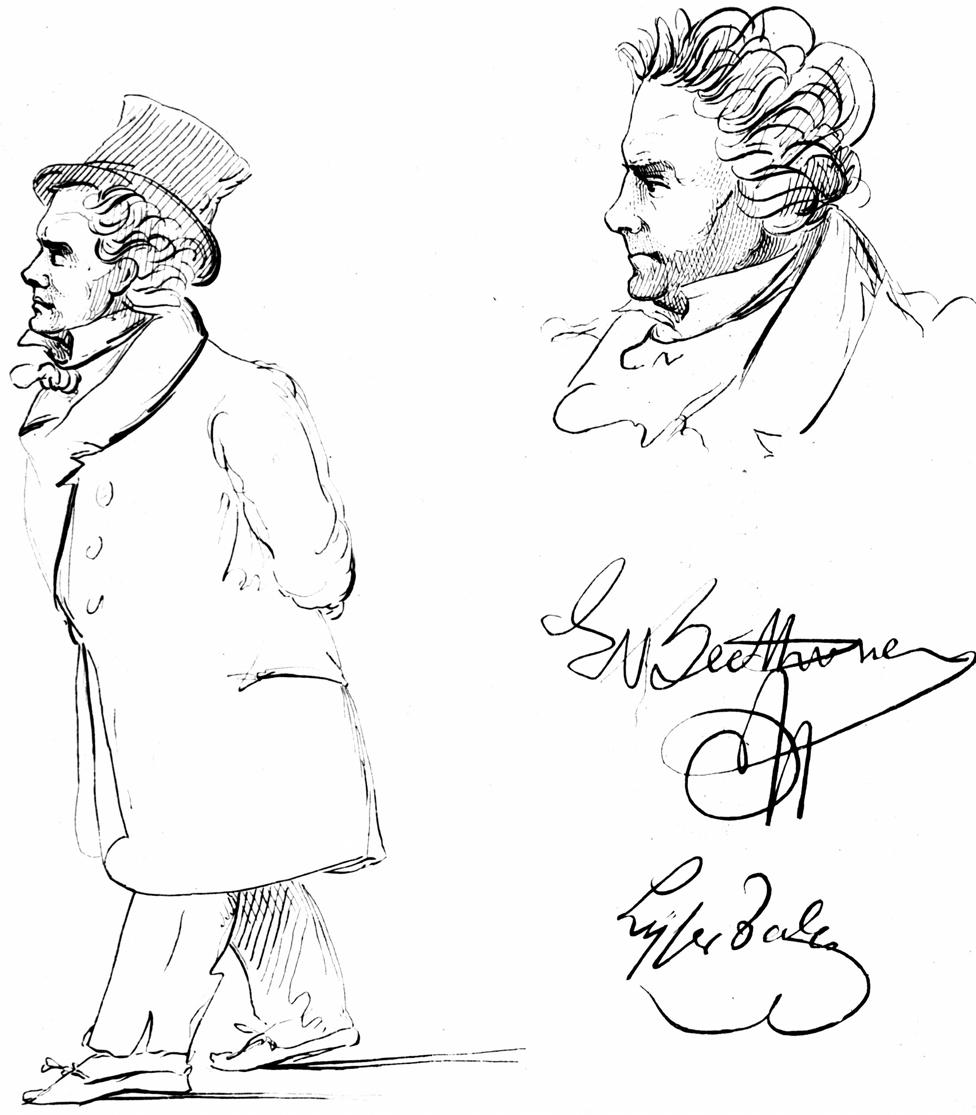

And a casual glance at a shop window as you pass by catches you walking more bent. Two choices. One, play the part. Beethoven, hands behind his back, bent into the wind, hair flying, as he composes the Pastoral Symphony? Or you straighten up and walk younger, more youthfully, a sprightly step, just in case anyone else had noticed the elderly slouch. No-one has of course because no-one is looking. But I noticed. I do the Beethoven walk into the wind, humming the Pastoral. Good choice.

In truth of course, you hardly need mirrors to remind you that the years are marching on. There are plenty of other signs you can't avoid noticing. You have to think before you bend down to pick anything up, or tie up a shoelace. There are baths too deep to get out of, so you have to turn turtle and push yourself up and out. But at least no-one is looking. Then there are far too many kind people these days offering you a seat on the bus or the underground. Your little grandson outruns you easily on a country walk, and no longer just because you are pretending to let him win. You can pretend you are pretending, if you like; but he's not fooled, no-one is fooled. I'm not fooled.

And these days I'm finding there are far too many visits to doctors and nurses, wonderful though they are. I was used to tests when I was young - vocabulary tests, comprehension tests, spelling tests. It's blood tests now.

Then there's losing old friends, and neighbours, and family. Not sure you ever get used to being an orphan. That's maybe the worst of being old, and getting older. There are more people you miss, and with every one that goes, you are more alone.

Find out more

Listen to Michael Morpurgo reading this essay on BBC Sounds

You can hear his thoughts about stress and anxiety among children on A Point of View, on BBC Radio 4, at 08:48 on Sunday 6 October - or listen now online

You find you are now among the last old trees in the park, wary of wild winds of fortune that might weaken you or uproot you. I'm sad sometimes that the world changes too fast around you and you feel you cannot belong, you cannot keep up. As a child I never liked feeling left behind. "But you are in second childhood, Michael," I tell myself. "Get used to it. Mustn't worry about sans eyes, sans teeth, sans everything. If it's another childhood you are living through, just be thankful for it. It means there's more ahead, more to look forward to, to live for."

So am I downhearted? No.

Reading to children in a book shop, in 2003

What keeps me going are the young, and the very old, the remarkably old. The young are beacons that burn bright with new hope, new energy, with the beauty of fervour, the joy of discovery. To be with them, to work with them, is to be inspired, feel the enchantment and excitement of youth again, to share it, to live in its glow. With them, around them, playing, talking, working, the years peel away. Age no longer wearies. When they've gone I know they have tired me, but I sleep deep and wake contented, refreshed, younger in heart.

Michael Morpurgo reads a story to a group of schoolchildren from London, and the Duchess of Cambridge

Just as rejuvenating and energising to me are the examples of those who have lived long, and never aged, some of the generation before me, whose lives have been lived fully, who have stayed positive to the end, active, and who have contributed so much to all of us. They are my mentors. I will try to tread where they have trod, keep right on to the end of the road.

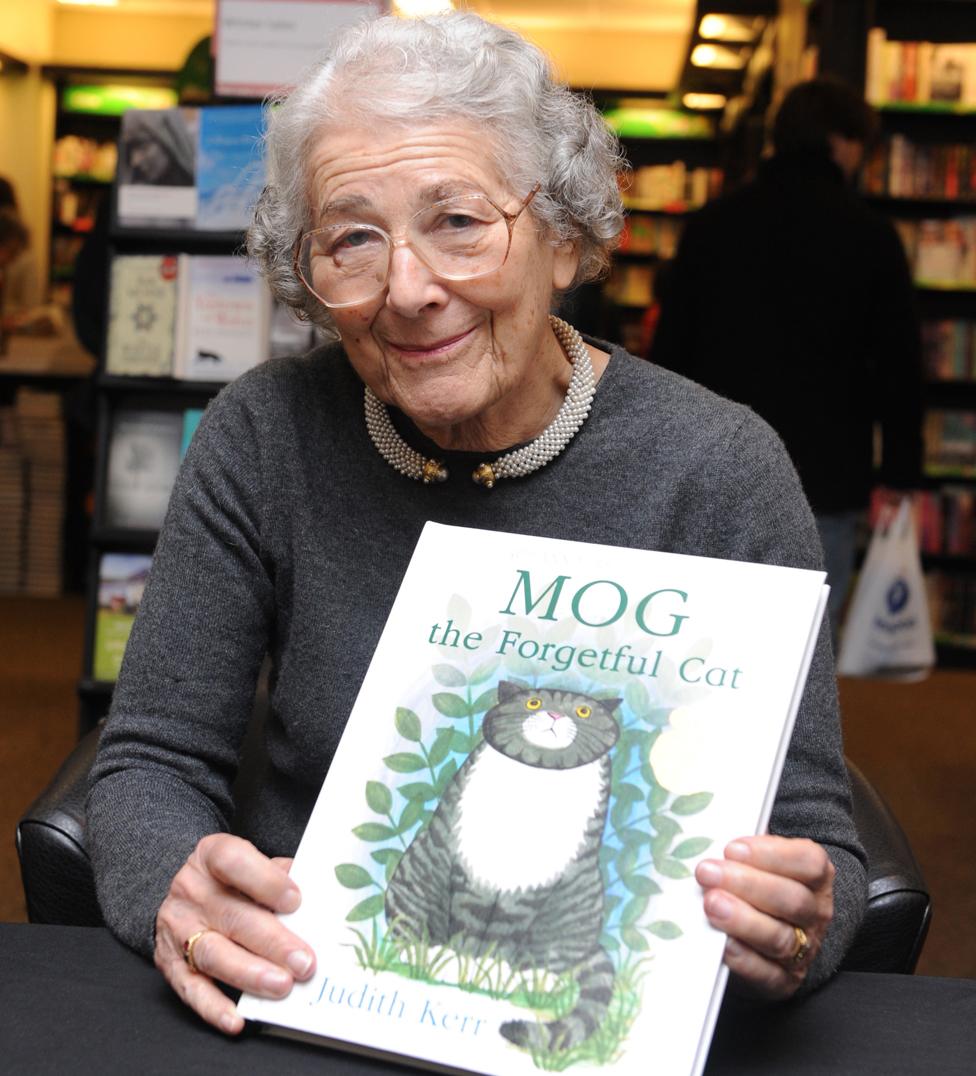

I think of Judith Kerr, author of The Tiger Who Came to Tea, and When Hitler Stole Pink Rabbit, and the Mog books, who passed away only recently, aged 96. She was at her desk, writing and painting, only a few weeks before she died. Well into her 90s she remained indefatigable, travelling widely, in this country and abroad, talking and drawing in schools, in libraries, at festivals, living life to the full. She walked four or five miles every day, ran up the stairs to her studio, loved to be with her friends, enjoyed good conversation, and a good whisky last thing at night.

She was a child refugee from Nazi Germany, had lived through family tragedy, through loss and grief, put up with living alone, worked through being alone. She had her memories, had her cat, her family and friends. She loved making her books, meeting families and children who loved them. And what a legacy of joy she has left! If she was ever downhearted, and I'm sure she was, she just went on dreaming her stories and characters up, went on writing, painting, walking, running up her stairs, kept right on. I walk sometimes where she walked along the Thames, from Hammersmith Bridge to Putney. Just to think of Judith puts a spring in my step.

We were in a restaurant in Oxford some years ago. A man came up to our table. He was old, but he walked tall. He explained he had just been to a talk I had given, told us how much he had enjoyed it, that his name was Roger Bannister. So I found myself speaking to one of my childhood heroes, the young doctor who had broken the four-minute mile, whose modesty was legendary. Having met him, and his wife Moyra, I discovered how, although running had brought him fame, it was primarily medicine, neurology, that was his life's work.

In old age, more and more immobilised by Parkinson's Disease, he continued his work, for his science, his athletics, his city, remaining active as long as he could, remaining an inspiration to us all. I recall well the determination on his face, as he willed himself through the tape that rainy evening in Oxford in 1954, when he became the first man in the world ever to run the mile in under four minutes, a determination that stayed with him all his life, that was with him in his wheelchair. The sight of him breasting that tape stays with me. The memory I have of him in his wheelchair the last time I saw him, still cheerful, still positive, reminds me that we have the power of the human spirit to keep us going, to keep right on.

Roger Bannister breaking the four-minute mile in 1954

In the village where we live in Devon we are a small community, with an average age of over 75. Every Tuesday lunchtime the pub, The Duke of York, puts on a lunch for the older villagers. It costs £5 a head for a three-course meal. Twenty or 30 will turn up, a chance to meet, to talk of old times, to remember together. The village consists of a couple of dozen cottages, a village hall - once the old school, closed over 60 years ago now - the pub, the church, the chapel. It is a living community that has a strong tradition of looking after our old people. Families look after their own elderly as best they can, so elderly are looking after elderly more and more. It is a place where the old are valued, respected and cared for. And it is a place where I witness daily the courage and dignity of the old. They too are my mentors.

I will try to emulate them all, Judith Kerr, Sir Roger Bannister, the old folk of my village, as best I can. I'll keep right on.

You may also be interested in:

Mollie Macartney's passion for planes began during her wartime service. Now she's taking to the skies herself - and passing on her appetite for adventure to her 12-year-old granddaughter.