Me, my camera, my brother... our cancer

- Published

When Carly Clarke was diagnosed with cancer in 2012, she set out to photograph how she changed during what could have been the last days of her life. Seven years on, by cruel coincidence, she is at her brother's side, photographing him going through the same ordeal.

"I have my own hair on my hands, on my clothes and down in the bath below me. As I wash, then brush, more continues to fall out.

"In the mirror I can see my appearance change, strand-by-strand."

Carly Clarke is reliving her experience as a cancer patient, showing me one of the many self-portraits she took during six painful months of treatment.

Eventually, she would ask her dad to shave the last hairs from her head. She was just 26.

"I used to have a lot of hair. Now I look like a cancer patient," she notes.

Six months before these photographs were taken, Carly had been living out a dream in Canada - shooting a final-year university photography project in Vancouver's poverty-stricken downtown eastside.

She had been sick for months, with a violent cough, appetite loss and pain in her chest and back. Doctors had diagnosed her with illnesses ranging from pneumonia to asthma and warned her she could suffer a collapsed lung on the flight. But she had ignored them.

"I wasn't going to let this illness - whatever it was - get in the way of living my life," she says.

"In Vancouver, I could empathise with those with illnesses and addiction. My concern for my own life made me compassionate during the shoot."

Many of those she spoke to on the near-freezing streets had become hooked after taking strong opiates in hospital, as they were treated for serious conditions, such as cancer.

Three months later, Carly would need morphine herself to alleviate the pain in her chest and back, so she could sleep.

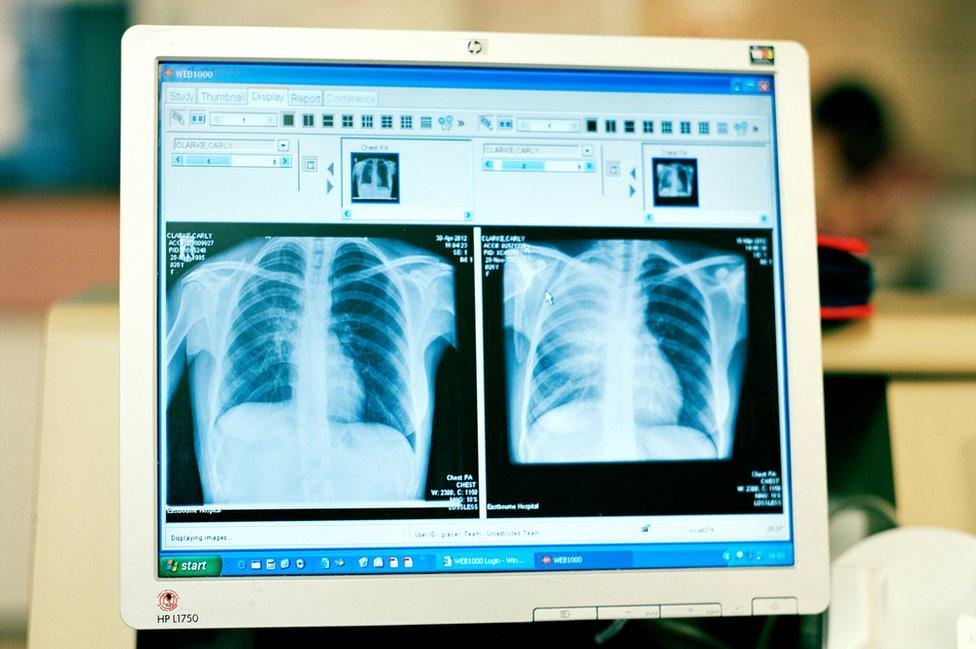

Persuaded by Canadian doctors to go home for specialist attention, she was finally diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma - a rare and quite aggressive form of cancer - in March 2012. A tumour the size of a grapefruit had already grown in her right lung and chest wall.

"I burst into tears at Guy's Hospital in London," she says. "I didn't know if I would survive the chemotherapy treatment, being diagnosed at such a late stage. I was terrified."

It was hard for her family to take.

"My parents felt like their stomachs fell out. There hadn't been a lot of cancer in the family," she says.

"My boyfriend was also devastated and he flew out from California to England to be with me."

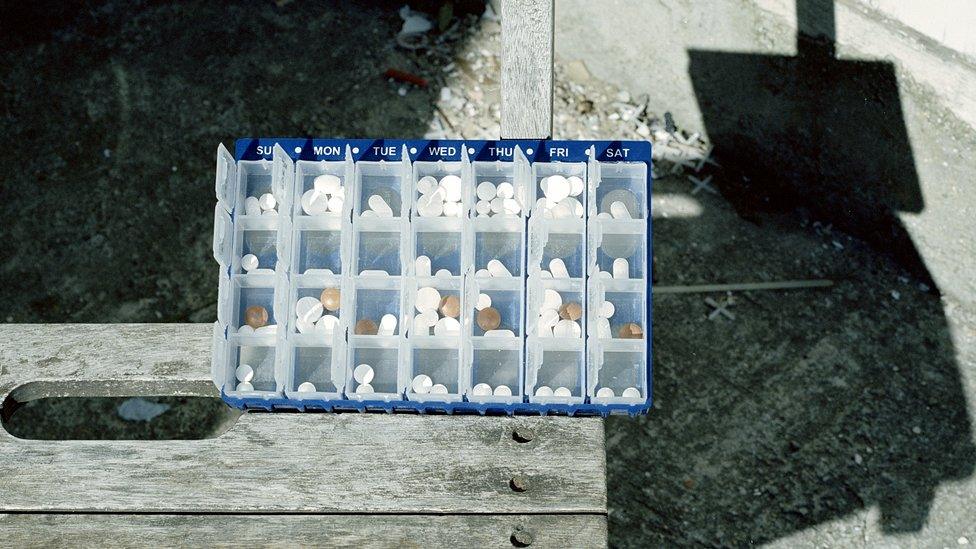

Back at home in Eastbourne, Carly scrawled hospital appointments and medication timetables on to a calendar that not long before had been packed with coursework deadlines and photoshoots.

"My life slowed down to concentrating on getting through each moment, drug to drug, endless examinations, giant needles, biopsies drilling deep into bone, tubes down my throat, and hoping for some day, the pain to end," she says.

Pain from her chest was now radiating down her arm, fluid on her lungs made breathing difficult, and she could not shake an "awful, non-stop cough".

"A plastic line through my arm fed sickening but healing medicine into my heart, trying to kill the cancer but taking my strength with it," she says.

"My skeleton became more visible by the day, a reminder of each precious pound lost. Out of nowhere my life was on the line."

Her view of the world - and herself - was changing. So she decided to photograph it.

"I thought that having a creative outlet would allow me to step out of some of that reality for a moment or two and think about my current trauma from another perspective," Carly says.

Reality Trauma was to be a series of self-portraits documenting her changing appearance, her life in and out of hospital, and her resilience.

During day visits, or short stays, the hospital gave her the freedom to use a tripod and cable release as often as she could. Doctors and nurses sometimes pushed the shutter for her.

"I thought about how others might view these images further down the line and whether or not I would even be around to tell my story," she says.

Carly wanted her work to inspire others to "have the courage to stare cancer in the face" and not let it take over their identity entirely.

Image-by-image, Carly noticed her skin was becoming paler and tighter around her bones, giving her an "unfamiliar, almost alien" appearance.

She lost around 12kg (26lb) in the space of two months and needed regular blood transfusions to make up for circulatory problems that were starving her body of oxygen and turning her blue.

"People were afraid to look at me. Especially, I think, parents with children also going through cancer - because they saw me and probably feared the worst for their own," she says.

"Seeing myself that way made me feel uneasy and frightened."

Soon afterwards, she found herself attending hospital so frequently she was admitted full-time.

At her lowest, constantly nauseous or asleep, she would reject all food from the hospital trolley. She was unable to study and, some days, too tired to photograph herself or phone her boyfriend.

By now she was also coughing so hard she would bring up blood. And sometimes she would wake after a night of cold sweats, itching and drenched as if she had showered in her hospital bed.

But then one day, after about three months of chemotherapy, the coughing stopped. Her other symptoms also began to ease.

The treatment was working, she thought. Biopsies confirmed it: the cancer was losing.

Her perception of life changed again.

"Helplessness turned into hopefulness - and then euphoria. When you come so close to death, suddenly you want to live your life to the fullest."

The hospital ward went from being a place of pain to home. Staff became friends, and some patients even closer.

Now Carly would venture outside her room. The fish tank in the communal area of the ward attracted patients of all ages.

An elderly couple, being treated for different types of terminal leukaemia, would often undergo chemotherapy on the same day as Carly. One day, the husband said his wife had been told she would not make it to Christmas.

"I remember hugging her and wishing her well - that couple would never leave my mind."

As Carly began to feel better, she also started to connect more with the world outside.

Her boyfriend and friends would take her for lunch, sometimes driving to Beachy Head - where white cliffs meet the sea - and Carly would talk about the future while watching boats move slowly across the horizon.

From course mates and tutors, she began to realise that her photographs were affecting other people.

Not only were they capturing the physical and emotional effects of cancer treatment but demonstrating that it didn't always have to be scary - it could be positive, Carly says.

"Looking back at the images I had taken, it made me feel stronger because in those photos I was faced with an end-of-life situation but a part of me still believed I could get through it."

Carly began showing her work to other cancer patients and took portraits of some of them in the ward. It became a way of starting a conversation or putting a smile on their faces.

Carly's photographs captured the mood of those who had undergone successful treatment

"If it's true that a simple smile, small gesture of help or kind word can change how a person feels and brighten their day, and have a positive effect on every cell in one's body, then a positive photographic story can help change someone's life," says Carly.

"It can be the defining factor in someone's mental strength and affect their willpower enough to keep them going through the suffering in hope that it will soon end and that, in my opinion, is what helps to keep you alive against all odds."

As Carly's treatment came to an end, in September 2012, she could look back through each phase of her journey, in 15 rolls of film and 150 photographs, and say she survived cancer.

Her image titled Last Day of Chemotherapy was shortlisted in the Portrait of Britain Awards 2018

It was a moment for celebration, but returning to the family home - to "piece her life back together" - was not easy. When she took back her boxes of unused medicine, she felt sad she was no longer in hospital.

"The hospital staff and some of the patients felt like family to me because we had built a very close relationship over many months."

A few months later, Carly flew to California and stayed with her boyfriend for most of the following year.

She returned home several times, and visited the hospital ward for the first of her twice-yearly check-ups. Every time she went back, she looked around for old faces: nurses who had treated her, patients she had shared moments with.

On one occasion, a few years after finishing treatment, she arrived early for a consultation and sat alongside a woman in the waiting area.

"We casually glanced at each other and suddenly tears came to my eyes."

It was the woman whose husband had told Carly she would not live to see Christmas back in 2012.

"I couldn't believe it was her," Carly recalls. "Moments like this are beautiful."

Carly quickly rediscovered her hunger to document the lives of people around the world. In 2014, she spent four months in India.

Her work on that trip would garner honourable mentions in the International Photo Awards in 2018. That same year her "Last Day of Chemotherapy" photograph from Reality Trauma was shortlisted in the Portrait of Britain Awards.

She got work assisting photographer Michael Wharley, producing promotional images for Summerland, a forthcoming film starring Gemma Arterton.

As her inbox filled with awards invitations and her calendar with shoot schedules, she began drawing up a project concept with her local hospice, St Wilfred's, to take portraits of cancer patients in their last stages of life.

She wanted to document how terminal illnesses affect people's psychological state, and the ways patients spend their remaining moments, trying new hobbies or saying last goodbyes.

But that plan was halted abruptly in September last year by a phone call from her older brother, Lee.

He told her their younger brother, Joe, had been diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma - the very same cancer Carly had beaten six years earlier.

"We both shed tears on the phone," says Carly.

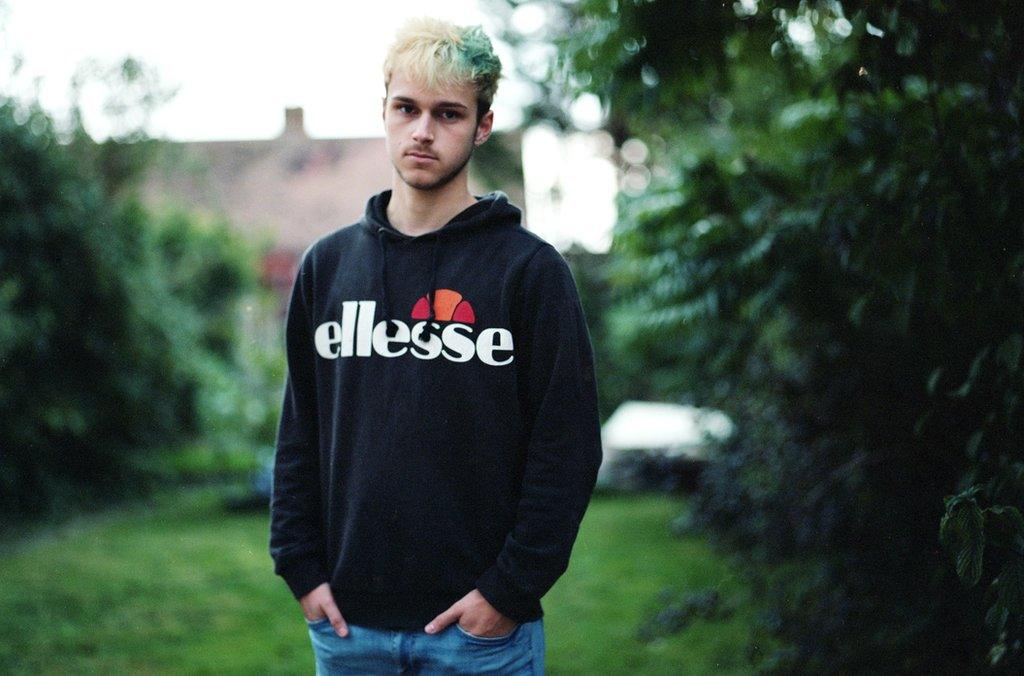

Joe was just 16 and starting college. His cancer was less advanced than Carly's had been but - just like his sister - he had also been ill for months before being diagnosed.

Doctors had initially put his severe itching down to "dry skin", or imagination.

"He wasn't prepared for his diagnosis. None us of were," says Carly.

Hodgkin lymphoma

The NHS says Hodgkin lymphoma is an uncommon cancer that develops in a network of vessels and glands called the lymphatic system. It can quickly spread throughout the body but is also one of the most easily treated types of cancer.

What is Hodgkin lymphoma?, external (Macmillan Cancer Support)

Joe tried to live as normally as he could, spending time with his girlfriend, learning to drive and making career plans.

But as he spent more and more time travelling to hospital and back, his grades took a hit and he began to lose touch with some of his friends.

Wanting to spend more time with him, earlier this year Carly asked if she could photograph his cancer journey. He agreed.

Sixteen years older than Joe, Carly had left home when he was still young. But, as his only sister, she had always felt a responsibility towards him, teaching him how to draw and paint when he was a toddler.

Later, when Carly moved to London for university, they saw each other only occasionally. With each visit, she noticed him stand a little taller, his voice slightly deepen.

But now she stood behind the camera in his hospital ward, she captured a rapid change with every photograph.

The hair he'd dyed blonde and then coloured flamboyantly, knowing it would fall out, came out in chunks until he shaved it off, as Carly had done, to stop it getting all over his clothes and bedroom floor.

He began covering his head in the photos, and talked about wearing a wig.

The steroids he took in preparation for the next stage of chemotherapy aged him, and had another dramatic effect.

"Joe put on weight to the point where he was unrecognisable. The pictures also showed his stretch marks from the severe weight gain," Carly says.

More and more, Joe reached out to Carly for support and advice. As a young boy he'd seen her go through cancer; he knew what the illness had done to his sister, but he also saw her defeat it.

"Even when he had doubts and misgivings, the fact that I recovered meant I could provide him with the hope and positivity to continue his treatment," she says.

Because Joe's cancer was less advanced, she thought his treatment would be quicker and her photographic series shorter. The collection would represent the journey of a young man overcoming cancer.

But Joe's first round of chemotherapy was unsuccessful.

"The news shook everybody up a lot. Our relationship changed, it became a little more unstable," Carly says.

Having suffered a relapse, Joe would have to endure four more months of chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplants. His hair, which had begun to grow back, fell out again.

Joe said he no longer wanted to be photographed - a decision Carly says she understood and respected - but with time came greater determination and fresh positivity. A month or so later, he changed his mind again.

"The image I liked most was him turning away in a contemplative manner. There, he knew what was to come, and his eyes glared into the distance," Carly says.

"It showed how he had changed and how he had adapted to this role of being a young cancer patient."

Against his consultant's advice Joe stopped stem-cell treatment. He feared the side-effects - the breathing trouble, skin problems, jaundice and diarrhoea that can occur if donor cells attack the host - would blight his life.

And shortly after taking that decision, in May, his scans came back clear. It meant that he was put into remission and able to join his family on holiday in Menorca, and then at Lee's wedding.

He will have regular appointments over the next few months to monitor his condition, but he has lost the weight he gained and his hair is finally growing back again.

Carly says her images offer stark evidence of how reality changed for the family during a time in which both her and Joe's "body, mind and soul were tested to the ultimate ends".

"These photographs I have captured, of both Joe and I, evoke some painful memories for me; however, they also remind me of the huge capacity of the human body to endure through such hellish times.

"This collection of images may give only a glimpse into those times but my hope is that an audience can see not just the horrifying aspects, but also the promise that being a survivor of cancer gives and the tremendous hope for others facing a similar condition."

Photographs: Carly Clarke