Separated at birth: Was my mother given away because she looked white?

- Published

When a health emergency prompted Nathan Romburgh and his sisters to look into their family history, decades after the end of apartheid, they uncovered a closely guarded secret that made them question their own identity.

Cape Town, 29 September 1969 - at 10pm the city is rocked by a huge earthquake. Margaret Buirski is working as a First Aid nurse in the Alhambra cinema and, for once, her medical skills are really needed. A woman has fallen from the balcony and Margaret is tending to her injuries in the chaos.

A young man walks past, very drunk, and notices the nurse's shapely legs. Despite his inebriation, he offers to drive the women to hospital. This is the start of the romance between Margaret and Derek Romburgh.

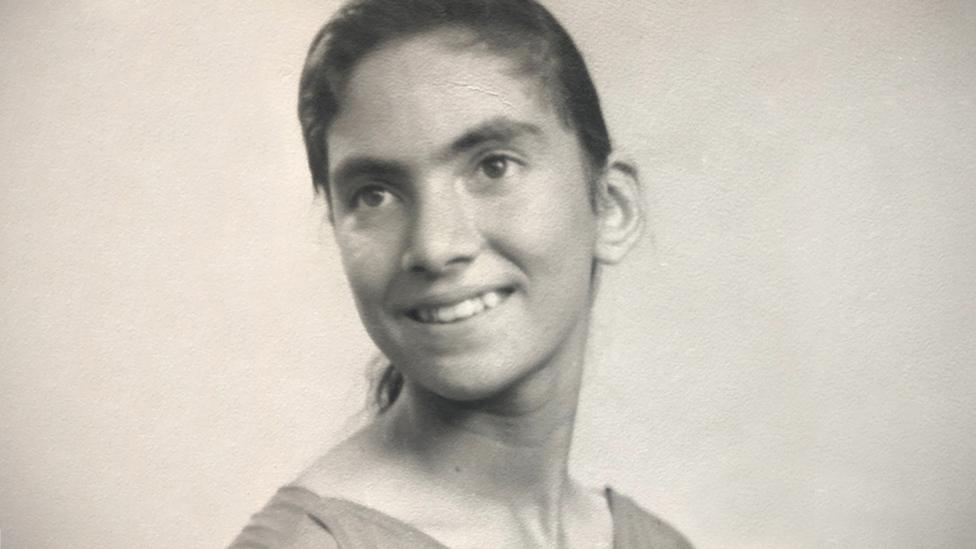

Margaret in her nurse's uniform in front of a St John's ambulance

"We always say that they met during an earthquake and from there worked up to a crescendo," says Nathan Romburgh, 42, their youngest child. He describes his mother as "a character". "She could talk herself into any job, and then straight back out again," he says.

The marriage was not a happy one. Derek continued to drink, and they had very little money. Margaret dealt with it by creating a fantasy world, telling the children that they were too rich to need a mortgage, and that they were going to install a lift in their house. The children never knew what to believe.

"She was a fantasist," says Nathan. "I think it's part of how you deal with a difficult life, you have stories in your mind - and we just grew to discount those."

"She was a bit of a compulsive liar," agrees Bernadette, Nathan's oldest sister. "We never knew if any of it was true - I'm not sure she even knew."

The children - Bernadette, Shereen and Nathan - knew very little about their mother's past and never met her adoptive family. She had been adopted as a baby by devout Orthodox Jews, who had died when she was a teenager. The rest of the family disowned her when she married Derek, a non-Jew.

Margaret's adoptive father died when she was a teenager

Despite this, Margaret had always clung proudly to her Jewish identity.

"We had a bit of an odd life, growing up, because my mother was Jewish and my father was not," says Nathan. "For Passover we would be fasting and not allowed to eat anything leavened, and in the middle of it my father would bring home hot-cross buns."

Nathan had a difficult relationship with his mother and when their parents divorced in 1991, he chose not to live with her, moving in with his paternal grandparents instead.

"There's no sugarcoating it - she was a terrible mother," he says.

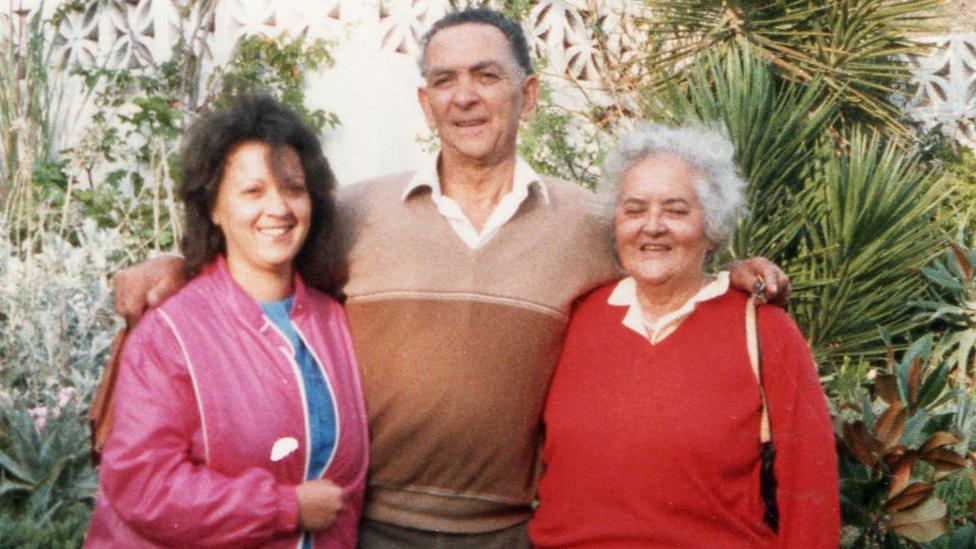

Bernadette, Nathan and Shereen with their parents at a family wedding

Three years later, as Margaret was dying of breast cancer, she made an announcement: she had a sister. Her children dismissed it as just another of her made-up stories.

Years passed, then, in 2008, Bernadette got breast cancer, too.

Genetic tests showed that Bernadette's cancer was the same type as her mother's, although the mutations did not sit on the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes - an aggressive form of inherited cancer, external that occurs more frequently in the Ashkenazi Jewish community than in the rest of the population.

"It scared us a lot," says Nathan. "We decided that we really ought to know a bit more about our exposure to things from my mother's genes."

So, while Bernadette focused on getting through treatment, Nathan and his sister Shereen set out to find out more about their family history.

Bernadette, Nathan and Shereen at Nathan's wedding

The first thing they did was to request Margaret's birth certificate. This took several months to arrive - but when it did, it contained a big surprise: they learned that their mother's mother was called Mary Magdalena Francis, a name that could hardly be more Catholic.

"We realised that my grandmother wasn't Jewish," says Nathan.

It was a mystery, and prompted them to delve further.

Nathan was living in London by then, so he asked his sister Shereen to phone every Francis in the Cape Town phonebook.

"The fourth call hit paydirt - they knew my biological grandmother," he says.

After several further phone calls to potential relatives around the world, Nathan spoke to Alan Francis, then living in Spain.

"Um, I think we may be related," he began.

"We always knew there was a scandal!" was Alan's immediate reply.

"All my life, I knew there was a skeleton in the cupboard, but nobody would say anything," says Alan, 77.

"Aunt Mary always said to me: 'I'll tell you on my deathbed.' But she never did, bless her."

Mary Magdalena Francis had died of stomach cancer in 1998 - four years after her daughter had died of breast cancer.

And Nathan discovered that his mother had been telling the truth after all, she did have a sister. Her name was Norma. But she, too, had died - of bowel cancer - in 2006.

Alan filled Nathan in on what he knew.

Mary and her baby Norma had moved in with Alan's family in 1949, when he was seven, he said. Mary had lost her job and her parents were no longer alive, so she took refuge with her brother, Alan's father.

Alan knew that Mary had become pregnant by her boss, a married doctor with young children of his own, but he always felt there was more to the story - he remembers hushed conversations behind closed doors.

Norma with Alan Francis's parents

For Nathan it was disappointing to discover this when it was already too late, especially since it turned out he had lived just down the road from his aunt Norma in London.

Mary had moved to the UK and married later in life. Now, armed with her married name, Nathan searched UK records for Mary's death certificate, and also Norma's.

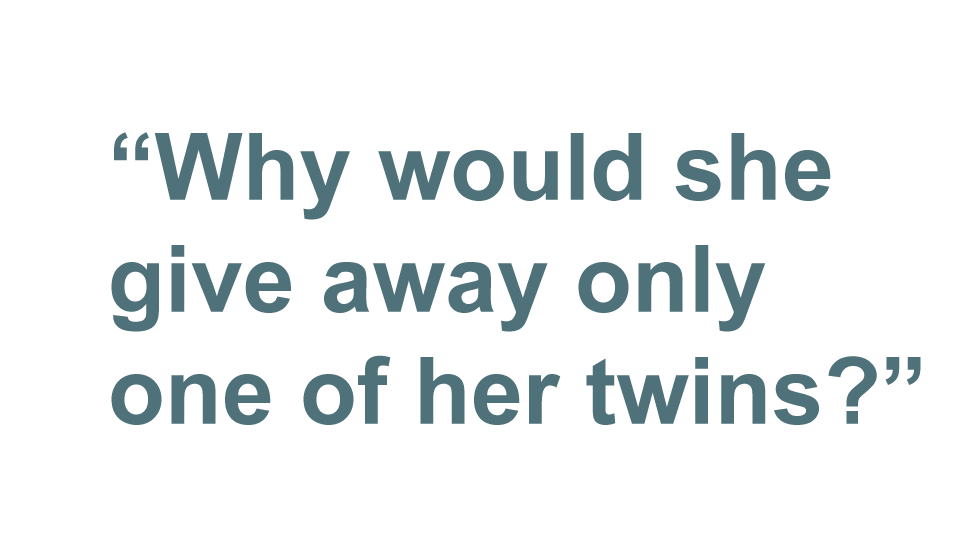

That was when he made a shocking discovery: his aunt Norma and his mother shared a birthday.

The secret Mary had taken to her grave was that she'd given birth to twins - but kept only one.

"Then there was this big question - what would make someone give away only one of her twins? It just didn't make sense," says Nathan.

He soon formed a theory - it was based on photographs Alan had shared, which showed that Margaret was fairer than her sister Norma.

"My mother had olive skin, but she passed for white in apartheid South Africa," says Nathan. "I don't think Norma could have."

Although Mary Francis, Nathan's grandmother, was registered as "European", she was in fact mixed-race. Mary's father, James Francis, was British, and her mother, Christina, was of Malaysian origin, from the island of St Helena. Mary was the youngest of their six children.

James Francis, with his wife Christina Leonora and three of their children - perhaps Nora, Percival and Mary (on Christina's lap)

Since the first arrival of early colonisers, mixed-race relationships had occurred in South Africa - Dutch settlers had families with local Khoisan and Xhosa women, as well as with women from Malaysia or St Helena, some of whom had been brought over as slaves.

But after the National Party came to power in 1948, laws were passed that made such relationships illegal.

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act forbade marriage between "Europeans" and "non-Europeans" and became law on 8 July 1949 - a month before the twins were born.

The Population Registration and Immorality Acts of 1950 went further, prohibiting sexual relationships between people of different races and requiring everyone to register as a member of three race classes: "Black" (African), "White" (European), "Coloured". Later, a fourth, "Indian", was added.

These racial classifications were often decided on the basis of photographs or superficial observations, including the infamous "pencil test" in which a pencil was put in someone's hair - if they shook their head and the pencil fell out, they were classified as white, but if it stayed in, they were not.

But people of mixed descent could look very different, even within the same family.

"A Cape Coloured person could be anything from very pale with green eyes to someone who's quite dark," says Nathan.

It's impossible to know how the turmoil of early apartheid influenced Mary, but it's likely that it had some bearing on what happened to her babies. She kept the twin who would have been classified as "Coloured", and gave away the twin who looked "White".

She may have had no choice in the matter - perhaps the Jewish family that adopted Margaret rejected Norma because they didn't want a child who looked different from them. Or perhaps they only wanted one child, not two.

But Nathan believes Mary thought she was offering Margaret the chance of a better life.

"If you were a coloured woman and you had two babies, one of whom was white, I could see that it is entirely possible and actually quite probable that if you gave up your white baby you'd be doing it for altruistic reasons," he says.

"Essentially it seems like a bit of a Sophie's Choice scenario. I could think of no other reason why you would give up one twin and not the other."

Under apartheid, life became increasingly difficult for people of mixed descent, such as the Francis family.

Racial classifications governed all aspects of daily life - where people could live, what public transport they could use and what schools or hospitals they could use.

Transport was segregated

As a consequence, apartheid often split families where parents or siblings were classified as different races.

Alan Francis remembers this well. He was dark-skinned, with black curly hair, whereas his sister was fair-skinned with brown hair.

"At that time I wouldn't be able to walk down the road with my sister, I wouldn't be able to sit on the same park bench or go to the same cinema, go on the same bus - nothing," he says.

Nor could they earn as much money as white people.

So in the 1950s Alan's parents emigrated to the UK, and many members of the Francis family followed. Including, in 1956, Mary Francis and seven-year-old Norma.

Mary got a job with London Transport, where she met her husband, an engineer. Mother and daughter remained close and lived together for most of their lives.

Mary and her husband George on a London bus (third row back)

But did Norma ever know she had a twin sister in South Africa?

It seems that in the last few years of her life Margaret tried repeatedly to contact members of her birth family, but nobody responded.

And yet some people knew about her existence.

Roy Francis, another cousin who emigrated to Canada in the 1970s, remembers visiting a family friend in Cape Town in 1985, who asked after Mary's "other daughter". Roy was completely taken aback by the question.

"Through all the years, nobody in the Francis family clan ever spoke about another child in Mary's life," says Roy. "I felt that I would not open a can of worms so I decided not to discuss this with anyone."

He remembered that strange conversation though, in 1992 or 1993, when his cousin Nora, who also lived in Canada, received a letter from a woman in Cape Town who was looking for her birth mother, Mary Francis. She wrote that she had terminal breast cancer and was keen to make contact.

Nora was astonished to notice that this woman's date of birth was exactly the same as Norma's. But when she asked her own mother [Mary's sister] about it, her mother dismissed the letter, saying it was from a "crazy woman".

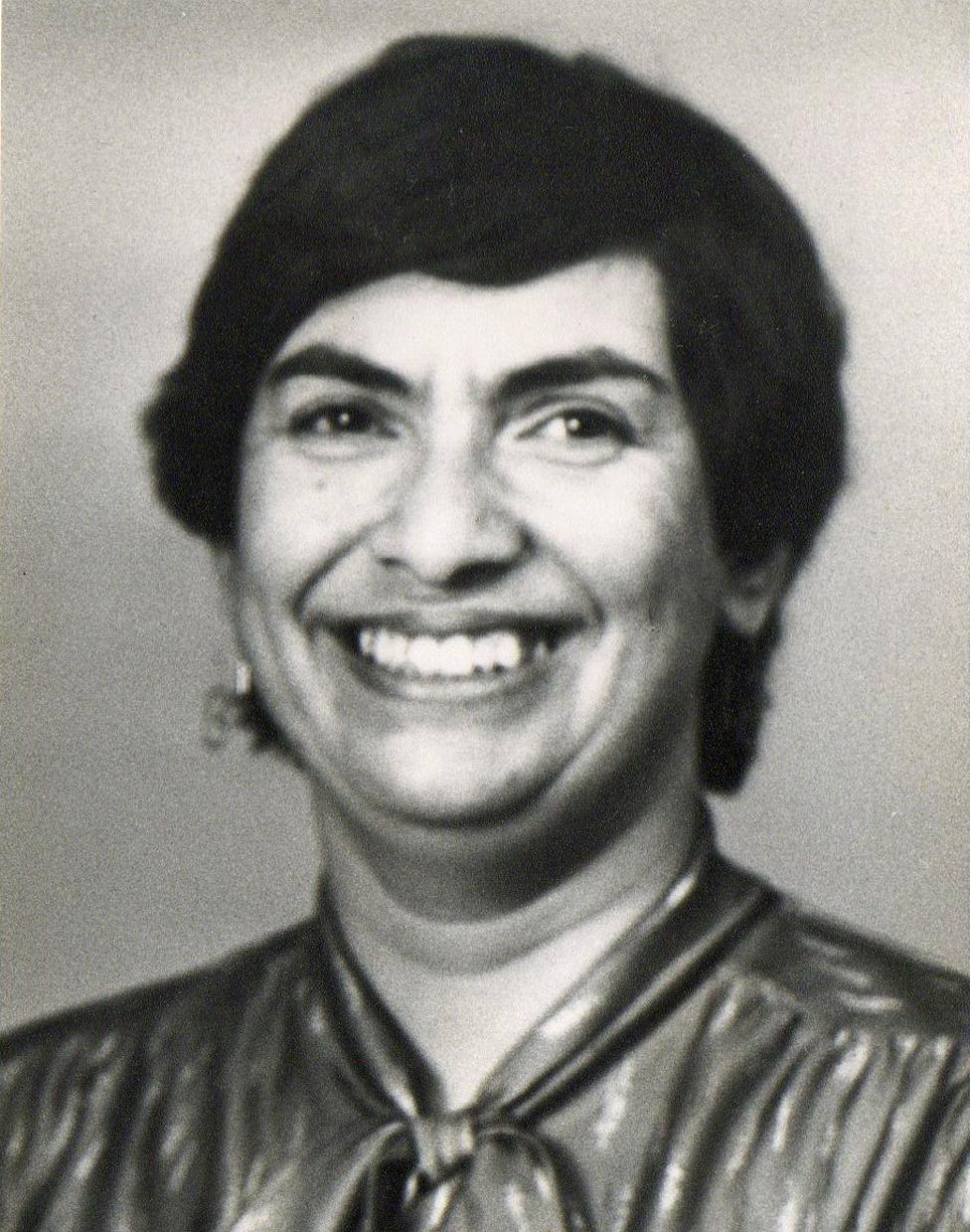

Norma Francis, Mary's husband George, and Mary

Norma herself never quite knew the full story, according to a close family friend, Crispin Belcher, who looked after her when she had cancer. During a hospice visit Norma confided in him that she had once picked up the phone in her mother's flat to hear a woman say, "I think you're my aunt."

Norma passed the phone to her mother, who listened, then said, "I don't want you to call any more," and put the phone down.

That was all Norma knew about it, says Crispin. He is surprised that Mary reacted that way. "She was always a very jolly person, but thinking about what I know now, that may have been a bit of a façade," he says.

Alan Francis can't understand it either. "It was uncharacteristic because Aunt Mary was the kindest, nicest person," he says.

Norma and Mary with Crispin Belcher's mother and sister standing in their garden in Croydon in the 1980s

Nathan began to feel sorry for his mother, when he discovered that her attempts to contact her family had been consistently rebuffed.

But he was excited about getting to know the Francises, and discovering his unexpected mixed-race heritage came as a pleasant surprise.

"It just added a little bit more depth to my origins, I was really quite proud of it," he says.

He set his hopes on finding relatives on the other side of the family and decided to trace his biological grandfather, who had employed Mary Francis, and got her pregnant. By this stage he knew he was called Dr Joshua.

Nora Francis, from the Canadian side of the family, remembered the doctor well, and she told Nathan that he was Jewish. She used to see him in the canteen of the Groote Schuur hospital, where she worked as a nurse.

"We knew exactly who he was," she told Nathan.

Groote Schuur Hospital (GSH) Cape Town, South Africa in 1969

Dr Joshua was thought to have emigrated, but Nathan could find no trace of him for years, despite writing to hospitals in the UK and Canada.

Finally, last summer, the BBC found Dr Joshua's name on an archived passenger list. It showed he had travelled to England in the late 1950s with his wife and son, and listed their full names.

Who's who?

Nathan, Bernadette and Shereen are the children of Margaret Buirski and Derek Romburgh. Margaret was adopted as a baby. Her biological mother was Mary Francis.

Mary Francis had another daughter, Norma, Margaret's twin. Norma was brought up by Mary and moved with her to London. The twins' biological father was a married doctor with his own family, Dr Joshua.

Nathan and his siblings discovered various relatives from their mother's family, including cousins Alan, Roy and Nora Francis.

Nathan also made contact in due course with one of Dr Joshua's sons. He's Nathan's mother's half-brother, which makes him Nathan's half-uncle.

Nathan immediately contacted the son via Facebook, and they spoke that same night.

Despite not knowing anything about Norma and Margaret's existence, the doctor's son was not entirely surprised to hear his father might have had illegitimate children.

"His father was, in his words, a 'ladies' man'," says Nathan.

He spoke to the man he hoped was his half-uncle at length, both of them learning a great deal from the other.

"It took a long time for him to work out that I was his nephew - I could tell when it clicked. He had an 'Aha!' moment."

He told Nathan that his father had strong links with the Jewish medical community in Cape Town, and therefore it was very likely that he had arranged Margaret's adoption.

However, he explained that Dr Joshua was not Jewish himself - he was also from the Cape Coloured community, with roots in St Helena.

His son told Nathan that his parents' reasons for leaving South Africa remained a rather sensitive subject.

Dr Joshua's wife was British - they had met when he completed his medical training in England. He took her back to Cape Town, where he set up practice in a building that belonged to the Francis family, as well as working in the Groote Schuur hospital.

As a non-white doctor he had become increasingly frustrated by the limitations imposed on him by apartheid. He was not allowed to operate without the "supervision" of a white surgeon, and was only supposed to treat patients from the same race classification.

For Dr Joshua and his wife, the final straw came when their children were no longer allowed to attend their "white" school. At that point the family decided to leave the country.

The doctor went on to have a successful career abroad, but he never got over the way apartheid had affected his life, his son told Nathan - and his background was something he did not speak about.

Reuniting families of the Cape Coloured community

"The Cape Coloured community was not very proud of their heritage - in fact it was frowned upon because it was shameful to be of mixed descent," says Jolene Joshua (no relation) who helps people trace their ancestry through her organisation, Find Your Roots.

The shame attached to being mixed-race had many layers, she explains.

Derogatory associations attached to Coloured identity included "immorality, sexual promiscuity, illegitimacy, impurity, propensities to criminality, gangsterism, drug and alcohol abuse."

Then there was the idea that Coloured people were a product of "miscegenation" - the interbreeding of people considered to be of different racial types.

Jolene says many of the people who come to her for help have no idea of their racial background. One of her clients couldn't trace her late father's UK birth certificate - but he turned out not to be British at all.

"He was slightly fairer so he could pass for white," says Jolene. "So she grew up in a white community, white background, supposedly white father."

Jolene knows of many "Cape Coloured" families who were split up because of racial segregation and never found their way back to each other.

"It is sad how many people are dying with unanswered questions," she says.

A DNA test has now confirmed that Nathan and Dr Joshua's son are related, and they have since met for dinner in London.

Nathan is happy to have made the connection.

"It's the last piece of the puzzle, and there's some completeness," he says.

Even so, learning that neither of his grandparents was Jewish came as a shock.

"I still haven't worked out how it affects my identity," he says. "Being Jewish is such a fundamental part of me that I was rocked by it."

Having found no record of Margaret's adoption, Nathan can't be sure that she underwent a full conversion, but he still considers himself Jewish.

"It's cultural, for me," he says. "It's what you were taught about yourself from an early age."

Nathan's sister, Bernadette, wonders whether her mother's strong attachment to the Jewish identity had something to do with her tenuous status as white under the apartheid system.

Margaret never fitted in, says her daughter Bernadette

"I suspect, given the wounds that she carried, that she always felt on the outside," she says. "She could definitely pass for white, and she did - but can you imagine spending your whole life walking that thin line?"

Bernadette's paternal grandmother had warned her, when she expressed curiosity about who her mother's family was, to "let sleeping dogs lie".

Bernadette suspects her mother's non-whiteness must have been apparent to the adults in the family. Her grandfather, who espoused the nationalist political views of the time, did not get on with Margaret.

"He did not have time for my mother," she says.

Nevertheless, the die was cast, and Margaret's children grew up with the advantages of being white under apartheid - something Bernadette, who became politically aware as a teenager in the 1980s, is acutely aware of.

"Even though my parents were working class people, the enormous amount of privilege we had in terms of being white was astounding," she says. "The fact I went to university on the most mediocre set of results - and got a bursary - is because I was white, not for any other reason."

Bernadette has long since recovered from the cancer that set them on this journey. And although they have discovered something of a family history of cancer in the family, any alarm they felt about this has been outweighed by interest in their new relatives.

Alan Francis especially felt like family immediately, says Nathan.

He has more sympathy for his mother now that he understands some of what she went through.

"Her life was unfair," he says. "Norma and her half-siblings had much more opportunity than she did, despite her adoption.

"It's made me feel more kindly towards her."

You may also be interested in:

In April 1997 a woman dressed in a nurse's uniform walked out of a Cape Town hospital carrying a three-day-old baby taken from the maternity ward as the baby's mother lay sleeping. It was only by chance, 17 years later, that the stolen child discovered her true identity.