How many people does it take to oust a political leader?

- Published

Which are more effective, violent or non-violent protests? And how big does a protest have to be, to drive a political leader out of office? One researcher, who has studied these questions carefully, thinks 3.5% of the population will nearly always succeed.

The Solidarity Movement in Poland in the 1980s, led by the unions; the long-running anti-apartheid movement in South Africa; the overthrow of Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic; the Jasmine Revolution against Tunisia's president, Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali, igniting the so-called Arab Spring…

These are all examples within living memory of popular movements that culminated in substantial political change.

The latest one making the news is in Belarus - where tens of thousands of people have taken to the streets following a disputed election, in which President Alexander Lukashenko claimed victory. The authorities have reacted with brutality; many demonstrators have been arrested and there have been numerous allegations of torture in detention. Despite this, the movement itself has remained largely peaceful.

So is it likely to succeed?

Well, one way to assess this, is to look at history. Which is actually what Harvard political scientist Erica Chenoweth has done.

Prof Chenoweth has focused her work on unrest mostly in dictatorships not democracies. Unlike democrats, dictators can't be voted out of office. In a democracy, if a policy is unpopular, politicians can be elected with the promise to abolish it. There's no such mechanism in a dictatorship.

There are definitional issues here. The definitions of democracy and dictatorship are contested. And there may be a spectrum - a political system may be more or less democratic. There is also the matter of how one classifies violence and non-violence.

Are attacks on property to be considered "violent"? What about people screaming racist abuse but without physical assault? What about acts of self-sacrifice - like self-immolation or hunger strikes? Are they violent?

Despite these difficulties of categorisation, there are some forms of protest that are clearly non-violent and others that are clearly violent. Assassination is clearly violent. Peaceful demonstrations, petitions, posters, strikes and boycotts, sit-ins and walk-outs, are non-violent. According to one well-known classification, there are 198 forms of non-violent protest, external. And by analysing every protest movement on which there was sufficient data, from 1900 all the way to 2006, Erica Chenoweth and co-author Maria Stephan reached the conclusion that a movement was twice as likely to be successful if it was non-violent.

The next question is - why?

The answer seems to be that violence reduces a movement's support base. Many more people will actively join non-violent protest. Non-violence is generally lower risk, it requires less physical ability and no advanced training. It usually requires less time commitment. For all these reasons, non-violent movements have higher participation rates from women, children, the elderly and people with disabilities.

And why does this matter? Well, take the so-called Bulldozer Revolution against Slobodan Milosevic. When soldiers were interviewed about why they never turned their guns on protesters, they explained that they knew some of them. They were reluctant to shoot at a crowd containing their cousins, or friends, or neighbours. And, of course, the larger the movement, the more likely it is that members of the police and security forces will be acquainted with some of its participants.

Find out more

Listen to Erica Chenoweth in How to topple a dictator, an episode of The Big Idea, on the BBC World Service

In fact, Erica Chenoweth has come up with a very precise figure for how large a demonstration has to be before its success is almost inevitable. The figure is 3.5% of the population. That may sound small but it's not. The population of Belarus is just over nine million - and so 3.5% is over 300,000. The big demonstrations in the capital, Minsk, are estimated to have involved tens of thousands, or perhaps 100,000, external, though the Associated Press once put it as high as 200,000, external.

The 3.5% rule is not iron-clad. Many movements succeed with lower rates of participation than this, and one or two fail despite having mass support - the Bahraini uprising of 2011 is one such example Chenoweth cites.

Chenoweth's original data took her up to 2006, but she's now completed a new study that examines more recent protest movements.

And while her latest findings generally reinforce the initial research - showing that non-violence is more effective than violence - she has identified two interesting trends. The first is that non-violent resistance has become by far the most common method of struggle worldwide, much more so than armed insurrection or armed struggle. Indeed, between 2010 and 2019 there were more non-violent uprisings in the world than in any other decade in recorded history.

The second trend is that the success rate of protest has declined. It has declined drastically with violent movements - around nine out of 10 violent movements now fail, Chenoweth says. But non-violent protest also succeeds less often than it used to. Before, around one in two non-violent campaigns succeeded - now it's around one in three.

There have, of course, been some dramatic results since 2006. The Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir, was deposed in 2019, for example. A few weeks later, popular unrest forced the resignation of the Algerian president, Abdelaziz Bouteflika. But these oustings are becoming rarer.

Why? Well, there could be many explanations, but one would appear to be the double-edged impact of social media and the digital revolution. For a few years, it seemed that the internet and rise of social media had furnished protest organisers with a powerful new tool. They've made it easier to transmit information of all kinds - for example, where and when to congregate for the next march.

But despotic regimes have now found ways of turning that weapon around, and using it against their opponents. "Digital organising," says Erica Chenoweth, "is very vulnerable to surveillance and to infiltration." Governments can also use social media for propaganda and to spread disinformation.

Which brings us back to Belarus, where detained protesters' telephones have routinely been examined, to establish whether they follow opposition channels on the Telegram messaging app. When the people running these channels have been arrested, Telegram has hurried to close down their accounts, external hoping to do so before the police have been able to check the list of followers.

Can President Alexander Lukashenko cling to office? Can he really survive now it's so clear that there is such widespread opposition to his rule? Maybe not. But if history is any guide - it's too early to write him off.

David Edmonds is the presenter of The Big Idea, on the BBC World Service

You may also be interested in:

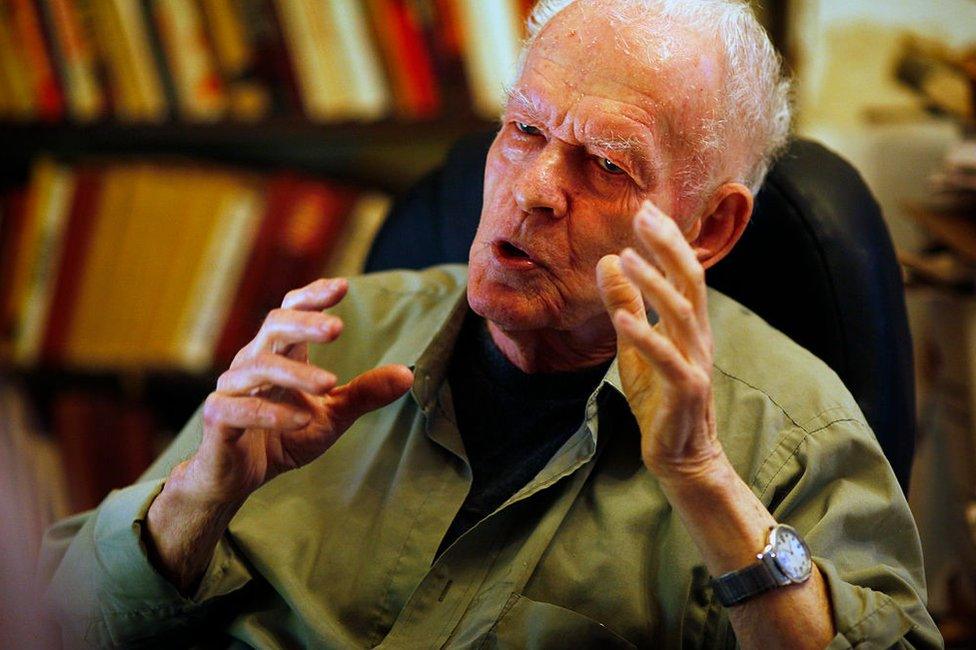

Gene Sharp may have had more influence than any other political theorist of his generation. His central message is that the power of dictatorships comes from the willing obedience of the people they govern - and that if the people can develop techniques of withholding their consent, a regime will crumble.

READ: The author of the non-violent revolution rulebook (2011)