Voicemail from prison: How a mum and daughter rebuilt their relationship

- Published

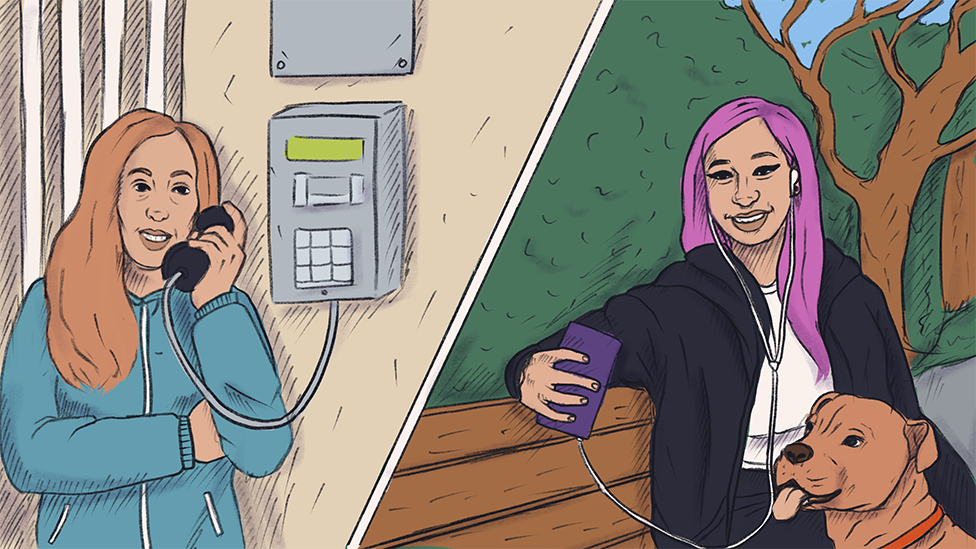

Staying in touch with a loved one in prison can be hard - but a simple voicemail app is making it a lot easier.

A year ago, Clare had a call out of the blue from an unknown number. She knew the voice in an instant, but hadn't heard it for years. It was her mum, Kath. She said she needed help, and didn't have anywhere else to go.

Clare was wary, and unsure what to do. "Part of me was quite angry that she felt like she could come back in my life."

But she quickly bought some clothes and toiletries and went to meet her mum in a park, and they talked and shared a bag of chips. It was the first contact they'd had in a long time.

Kath was in a bad way. "I was homeless. I had active mental health issues. I was in the throes of a big heroin addiction," she says. "I was in quite a state, to be honest."

A few weeks later, she pleaded guilty to drugs offences and was sentenced to two years and nine months in prison.

Kath had had quite a difficult childhood. Her dad had been in prison, and she'd had Clare when she was a teenager. Growing up, Clare had been aware that her mum took drugs - not frequently, and not hard drugs, but the signs were there.

"It wasn't, you know, the whole nuclear family, white picket fence, but she did try," Clare says. "She did really, really try and I do have quite a few good memories."

Kath had blonde highlights and a belly bar [navel piercing]. Clare remembers listening to drum and bass on the way to school, full blast in the car.

At one point they lived in a flat with her mum's then-partner and a Staffie puppy. Clare remembers coming back from Scout camp and the little dog running down the hallway to meet her, with her mum behind him, just as excited to see her. By the age of 12 she was the taller one, and in a tight hug she could rest her head on top of her mum's.

They moved around a lot and Clare remembers some questionable partners. Social services were heavily involved.

Later, when she was about 13, Clare went to live with her dad. She carried on seeing her mum for a couple of years but came to realise she was going down a path she didn't want to be involved with.

"If I had anything to do with that, my life wouldn't go where I wanted it to. So I decided that it would probably be best for me to cut a bit of a tie."

Clare had firm plans for her future. "Even at a very young age, I decided that I wanted to go into healthcare, which is what I'm in now," she says.

Now 21, she is studying for a degree while she works. She lives with her partner, has a dog, and feels safe and settled - a feeling, she says, "I never thought I'd have."

Which is why, when Kath first made contact, Clare responded guardedly, "not really seeing her as my mum".

"It was more like, 'Oh, you know, I'm just helping someone out.'"

But on the first prison visit, something happened. Clare remembers looking at her mum. "She was very skinny. She looked really, really ill. And she wasn't who I remembered at that point. I was sort of like, 'You know what? Why not?'"

Clare decided she was going to try to support her mum through her sentence, and quickly found that staying in touch with someone behind bars can be hard.

She sent letters and visited as often as she could. The journey to HMP Send, in Surrey, took four hours by public transport - this was before Covid hit and all prison visits were cancelled.

So the main means of communication was a payphone on Kath's prison wing, as prisoners are not allowed mobile phones. In HMP Send there is one payphone for 20 women on average, and they get 20 minutes each per day. In the resettlement wing, where Kath was, they can make calls until nine o'clock at night. But on other wings women can only access phones when their cells are unlocked.

This means that prisoners have a limited ability to make calls out, but their families can't ever call them. A missed call can be hugely stressful for both sides.

"When people are in prison, they are still someone's mother, father, sister brother," Clare says. "And although they should have some description of punishment, having a lack of family ties shouldn't be one of them."

Clare joined a Facebook group for people with a family member in prison, and posted about the difficulties she was having speaking to her mum.

Someone recommended an app called Prison Voicemail, which lets an approved contact leave messages for a prisoner at any time. The prisoner can access them from a payphone by calling their unique number and putting in a pin number.

So Clare signed up and left her first message:

Hi Mum, it's apparently a thing, it's like a voicemail, it's quite cool! I've got an app on my phone and everything… Um, I miss you I hope you're doing OK and it's not too hard or stressful. And I hope you've got a little bit of support at least.

She left a few more, updating her mum on what was going on in her life.

The person in prison can send messages back, using the payphone. This was Kath's reply, the first time she heard Clare's messages:

Oh my God, I didn't realise I could get messages. I just listened to yours they're amazing. It's so, so good to hear your voice. I didn't even know I had this [voicemail] until today, when they gave me the letter. But all your news is amazing! Your job, your tattoo, you're in a circus metal band? And you're coming to see me - oh my good God I'm so so so so damn excited. Um, it's really not that bad here, but to hear your voice is just the best thing ever… My money's going to run out but I miss you and I love you and I'll see you soon. Bye!

They carried on sending each other messages back and forth.

Listen to Clare and Kath's first messages

Clare works shifts, and Kath was working in the prison kitchens, so they found voicemail communication really useful.

There were times when Clare was working and couldn't answer when Kath had access to a phone, but they could still record a few words for one another, "just so we know we're thinking of each other," as Kath puts it.

The messages they left are snapshots of normal life, the ordinary chat that a relationship is built on.

Hi Mum, I got you a Christmas present! It's quite sweet... Just having a day off 'cos it's my weekend. Cleaning the floors, sorting out clothes, petting the cats. Yeah. I love you Mum. Bye.

It allowed them to get to know each other again.

Hello beautiful, that's very good about your maths course isn't it? That's wonderful news, that's exactly what you need for your plans to go ahead, I'm very pleased.

And over time they got closer.

Happy New Year! Happy New Year Mum, I love you. Bye!

The voicemail app is very simple, but has only been around since 2015. The co-founder, Kieran Ball, thinks no-one had made it before because prisoners and their families are not the sort of customer tech companies usually have in mind.

"No-one is trying to innovate. I mean it seems so obvious, in hindsight, but no-one had done it because people aren't trying to help the families of prisoners," he says.

Find out more

Listen to Messages behind bars on the BBC World Service

Download more podcasts from People Fixing The World

Kath found it really helped keep her spirits up.

"If she's listening to music that she remembers from her childhood, she leaves me little song clips on it," she told me, speaking from inside the prison. "And she'll always leave me a message saying that she loves me or just a little funny joke or something, just so I know that she was there, and she was thinking of me. It will just cheer me up."

Clare even shared her dog's new tricks with her mum.

Mum! Marcus can do something now, listen: Right Marcus, speak [Bark!] Speak [Bark!] Speak [Bark!] Good boy! He got the biscuit. I love you!

She didn't want Kath "to feel like everyone's moved on or forgotten about her".

While the messages helped Kath get through her sentence, they also helped Clare, on the outside. Last year, she had some serious health problems, and was rushed to hospital for an emergency blood transfusion. She felt dizzy and scared while she waited, so she put her headphones in and started replaying messages from the app, listening to her mum chatting away. "And it was sort of like she was there."

Oh so good to hear your poor little voice, I was so worried about you, oh my God.

Hearing her mum helped calm her down. "Because at the end of the day, I am only 21. And there's times where I do feel like I just need my mum, doesn't matter how old you are."

Family relationships are recognised by experts as a crucial part of rehabilitation. Ministry of Justice research suggests that prisoners who have visits and maintain family ties are 39% less likely to reoffend.

But Dr Lorna Brookes, who runs Time Matters, an organisation supporting children with a parent in prison, says regular contact also alleviates the effects of prison sentences on those left on the outside, especially children, who haven't done anything wrong.

"It reduces their separation anxiety, it reduces their worry about their parents' well-being," she says. It can also reduce the sense of isolation that they often feel, along with shame and grief.

It's estimated that parental imprisonment affects around 310,000 children in the UK, external.

Some campaigners argue that too many women are in prison in the first place - the Prison Reform Trust points out that 82% of women sentenced to prison in England and Wales in 2018 had committed non-violent offences, external.

In fact, the government's own Female Offender Strategy, published in 2018, external, made it a strategic priority to reduce the female prison population by increasing the use of non-custodial sentences, and to improve conditions in custody by taking a number of steps, including improving family ties. A subsequent review by Lord Farmer in 2019 drew attention to the high cost of calls made from prison payphones, external, which often consume women prisoners' entire weekly wage.

Clare says the Prison Voicemail app allowed her and her mum to rebuild their bond, and they are now closer than ever.

"I actually have a relationship with her for the first time in, probably about nine, 10 years. And that was a relationship I never ever thought I'd have again," she says.

Clare asked her mum to try to come off methadone by her 21st birthday. She knew that detoxing from the prescription opioid would be hard and there would be times when Kath would struggle. She knows that some prisoners take drugs inside. "There's ways to get things in prison and it would be ignorant to say that there isn't."

But Kath didn't, and she got clean three weeks before the milestone birthday.

"I'm free of substances, I have been for months and months now. I've worked through lots of issues and therapies and I am clean for the first time in about 12, 13 years," she says.

She thinks she would have been able to detox without the contact with Clare, but it was a huge help.

"Even if it's 20 minutes a day, you need to be able to just have that connection with your loved ones. It would have been a lot harder to deal with if I hadn't been able to do that.

"It just reminds you that there's people there for you, that you're loved. Ultimately, you have to fix yourself for yourself, but there's people that are rooting for me."

A week ago, Kath was released from prison and Clare could not be more pleased to have her mum back.

"She's healthy now and I am more proud of her than I think I would ever have been in any other situation. I'm ridiculously proud of her."

All right darling, I love you lots! I love you. Take care. Bye!

Illustrations by Camilla Ru, external

If you want to hear the messages and find out more about the Prison Voicemail app, external have a listen to the People Fixing The World podcast

You may also be interested in:

For many people, receiving a jail sentence would be the worst thing that ever happened to them. But when you've been experiencing domestic abuse - as most female prisoners have - you may see things slightly differently.