Choice blindness: Do you know yourself as well as you think?

- Published

Asked to make a choice between two things - two faces, or two politicians, perhaps - you may think you know very well the reason you picked A rather than B. But do you? A Swedish psychologist thinks you don't.

You're shown two pictures - two women, or two men - and you're asked to rate which one you find most attractive. That's easy enough. But then you're asked to explain why.

That's harder. It might make you think. What is it you like about her? Is there something appealing about her eyes, perhaps? Or her hair? What is it about him? Maybe you like his strong jaw-line, or his perfect teeth.

But are these really the reasons you found one person more attractive than the other? Once you hear about Prof Petter Johansson's work, you may begin to have your doubts.

Swedish experimental psychologist Petter Johansson loves magic. He's not formally trained but he's taught himself some basic sleight of hand techniques. Magicians have long understood the phenomenon of "change blindness". By distracting you, a magician can change a card, say the King of Clubs for the King of Spades, and the chances are you won't notice.

Johansson's rudimentary magic skills are useful for his experiments - for, some years ago, he and his colleagues decided to test not change blindness but "choice blindness".

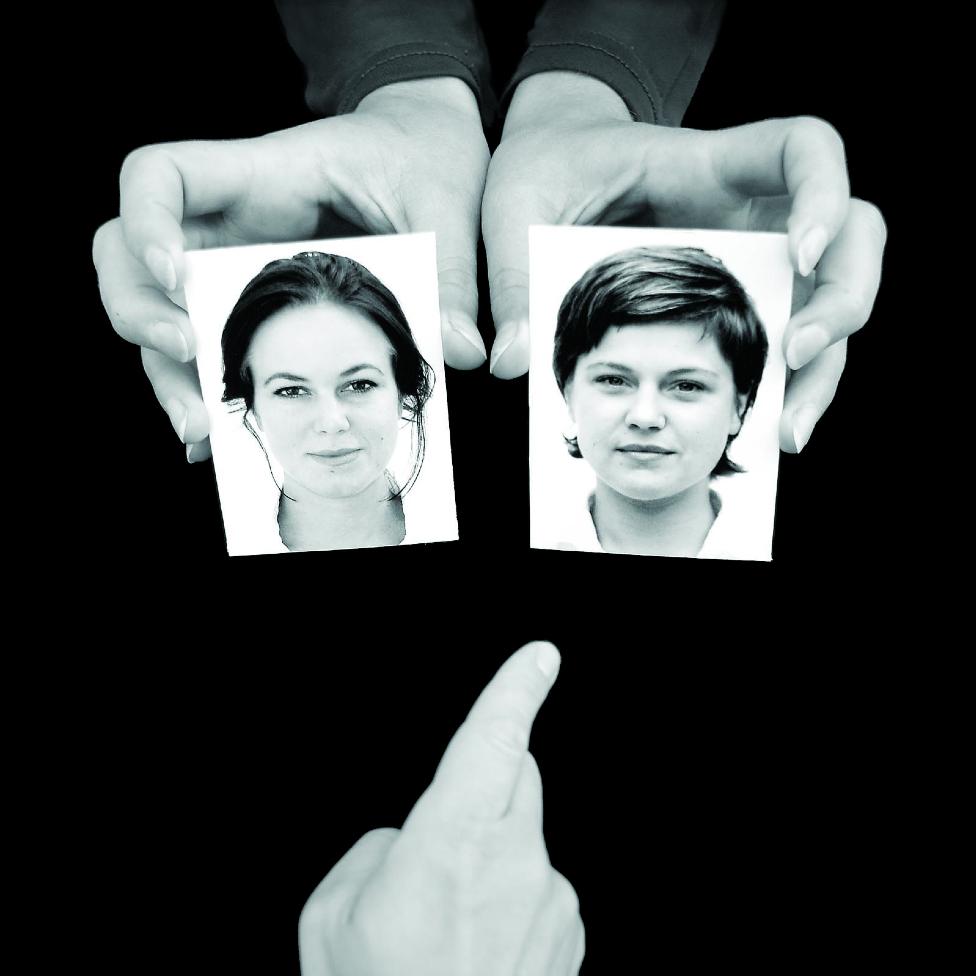

Let me explain. In his earliest experiment, Petter Johansson showed participants pairs of pictures of faces. The subjects had a simple task: to choose the one they found most attractive. Then they were given the picture and asked to justify their selection. But unbeknown to them, Johansson had deployed his magic to make a switch; they were actually handed the picture of the man or woman they had not picked.

Petter Johansson shows a female participant two photographs of men

You might assume that everyone would notice. If so, you would be wrong. Amazingly, only a quarter of people spot the switch. To repeat, the faces were of different people, and there were easily identifiable differences between them. One might be brown-haired and with earrings; the other might be blonde and with no earrings.

After the switch, the subjects explained why they had chosen the person they had actually not chosen! "When I asked them, why did you choose this face?" says Petter Johansson, "they started to elaborate on why this was the preferred face, even if, just a few seconds before, they had preferred the other face."

When he explained to them what he had done, he was usually met with surprise and often disbelief. The most intriguing cases were those in which people justified the manipulated choice by highlighting something absent in their original choice. "For instance, if they say, 'Oh, I prefer this face because I really like the earrings,' and the one they originally preferred didn't have any earrings, then we can be certain that whatever made them make this choice, it can't have been the earrings."

What can we conclude from this? Well, it turns out that we don't have a clear understanding of why we choose what we choose. We often have to figure it out for ourselves, just as we have to figure out the motives and reasons of others. The window through which we try to observe our own soul is dim and murky.

Why you believe one face is better-looking than another is hardly a trivial issue. Sexual appeal matters: the survival of the human species rather depends upon it. But Petter Johansson has also used his trickery to test our choices in another weighty domain - politics.

In one study, he asked a group of Swedish subjects a dozen questions about where they stood on political issues - such as whether there should be an increase in petrol tax, or whether healthcare benefits should be cut. These are topics which tend to divide the Swedish left and right. Their written survey answers were then handed to them, except - as you might by now have guessed - they were not the real ones. Left-wing people were shown answers which were more right-wing; right-wing people were shown answers that were more left-wing. And then they were asked to justify their selections.

Again, most people failed to spot the switch. A subject who a minute earlier had ticked a box supporting a rise in the petrol tax now proceeded to explain why they believed there should be no such tax hike. They gave explanations that made perfect sense. "They would say things like, 'Well it's unfair to the population living outside the major cities because they have to drive a lot more.'" So there was nothing odd about their rationalisation, except that a few minutes earlier they would not have supplied it.

Find out more

Listen to Petter Johansson in The fragility of choice, an episode of The Big Idea, on the BBC World Service

Clearly we lack self-knowledge about our motives and choices. But so what? What are the implications of this research?

Well, perhaps one general point is that we should learn to be more tolerant of people who change their minds. We tend to have very sensitive antennae for inconsistency - be this inconsistency in a partner, who's changed their mind on whether they fancy an Italian or an Indian meal, or a politician who's backed one policy in the past and now supports an opposing position. But as we often don't have a clear insight into why we choose what we choose, we should surely be given some latitude to switch our choices.

There may also be more specific implications for how we navigate through our current era - a period in which there is growing cultural and political polarisation. It would be natural to believe that those who support a left-wing or right-wing party do so because they're committed to that party's ideology: they believe in free markets or, the opposite, in a larger role for the state. But Petter Johansson's work suggests that our deeper commitment is not to particular policies, since, using his switching technique, we can be persuaded to endorse all sorts of policies. Rather, "we support a label or a team".

That is to say, we're liable to overestimate the extent to which a Trump supporter - or a Biden supporter - backs his or her candidate because of the policies the politician promotes. Instead, someone will be Team Trump, or Team Biden. A striking example of this was in the last US election. Republicans have traditionally been pro-free trade - but when Trump began to advocate protectionist policies, most Republicans carried on backing him, without even seeming to notice the shift.

Prior to the last US election - the bitterly contested 2016 race between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton - Prof Johansson tried another experiment. He asked voters to rate their preferred candidate on their character, experience and so on, and then he switched their answers, improving the ratings of the candidate they disliked. It worked. People offered reasons why they were actually quite open-minded between the two.

Remarkably, such legerdemain turns out to have a lasting impact. Fool a person that they believe someone with blond hair is more attractive than one with brown, and they are likely to confirm that preference when shown the two faces at a later date. It's the same with political views. After swaying the political preferences of his subjects, Petter Johansson tested their views the following week. Having had to justify their new preferences, it seemed "they had listened to their own arguments".

You may also be interested in:

Which are more effective, violent or non-violent protests? And how big does a protest have to be, to drive a political leader from office? One researcher, who has studied these questions carefully, thinks 3.5% of the population will nearly always succeed.