Christian Picciolini: The neo-Nazi who became an anti-Nazi

- Published

Just one conversation was enough to recruit Christian Picciolini into the neo-Nazi movement, but it took him years to get out. To make amends for his wrongdoing, he has spent the last quarter of a century persuading hundreds of others to make a break with extremism.

In the summer of 1987, Christian Picciolini was standing in an alley smoking a joint, when a man with a shaved head and tall black boots approached him.

"He pulled the joint from my mouth, looked me in the eyes, and he said, 'That's what the communists and the Jews want you to do, to keep you docile,'" Picciolini remembers.

At 14, he didn't really know what a communist was, or a Jew for that matter, and had absolutely no idea what "docile" meant. The stranger then asked what he was called.

"I was afraid to tell him because my last name, Picciolini, was kind of a point of contention growing up. It was something I was bullied for."

Instead of making fun of his Italian surname, the man told him that it was something to be very proud of, but that if he wasn't careful, somebody would take that sense of Italian and European pride away from him.

He touched a raw nerve. Picciolini's parents were immigrants who had moved from Italy in the 1960s, and he felt more Italian than American.

The man who approached Picciolini that day in the alley was Clark Martell, and the group that he had just been recruited into was America's first neo-Nazi skinhead group: the Chicago Area SkinHeads - also known as Cash.

Picciolini believes that Martell, then 28, was on the lookout for someone vulnerable.

"He saw that I was lonely, and I was certainly doing something that put me on the fringes already - smoking pot in an alley. He knew that I was searching for three very important things: a sense of identity, a community and a purpose."

The Chicago Area SkinHeads offered all three, and from that one conversation in the alley, Picciolini was ready to jump right in.

"It was the first time in my young life that I felt somebody had actually paid attention to me, and empowered me in some way," he says.

Despite having some doubts about the group's ideology, the rewards of inclusion and empowerment were greater than anything he had experienced before. The teenager had been bullied, and felt abandoned by his family, because they worked seven days a week, sometimes 14 hours a day, as owners of a small beauty parlour who sometimes took other work too.

Find out more

Christian Picciolini spoke to Outlook on the BBC World Service (producer Alice Gioia)

Picciolini started to listen to imported music from white supremacist movements in Europe, and really connected with the lyrics.

"They spoke to my angst of being young and unseen. They spoke to my frustrations of trying to get something done or trying to progress in my life. And those lyrics spoke to me by blaming 'the other' for those problems."

The songs also gave him a feeling of pride, painting white supremacists as warriors against subhuman races and religions - "parasites who were attempting to destroy this glory and heritage of the white race".

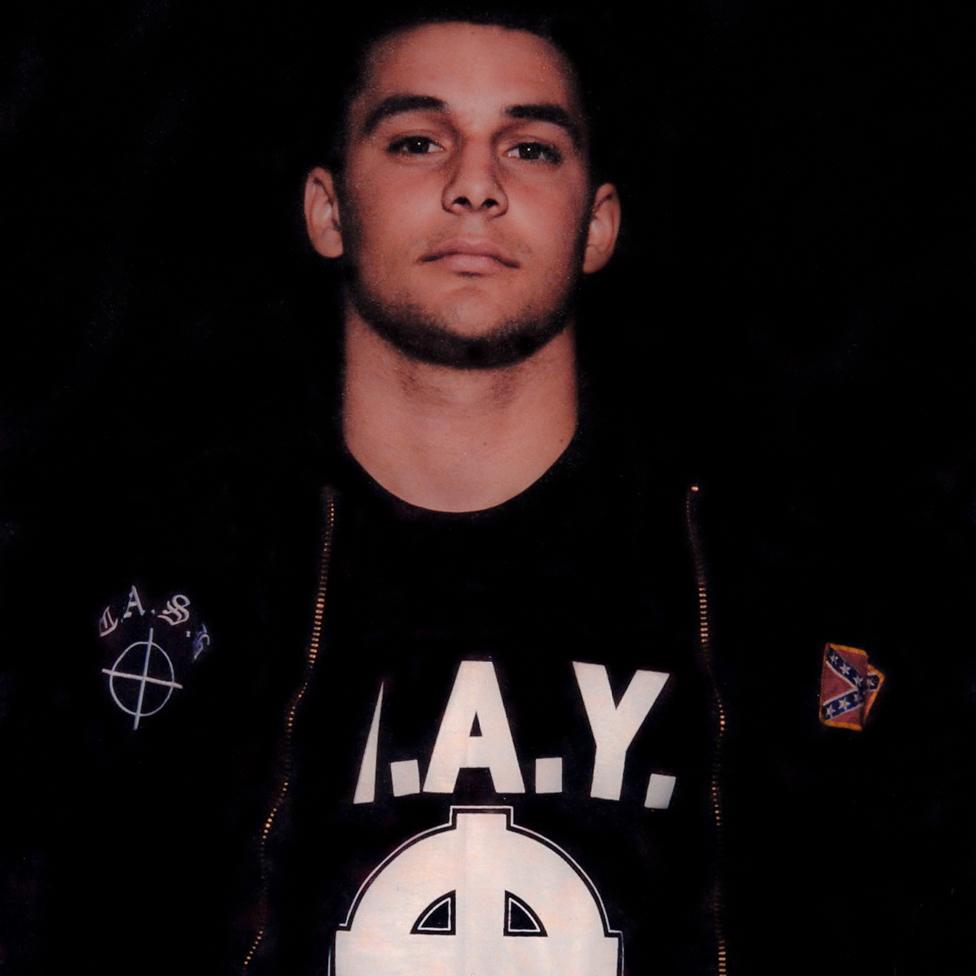

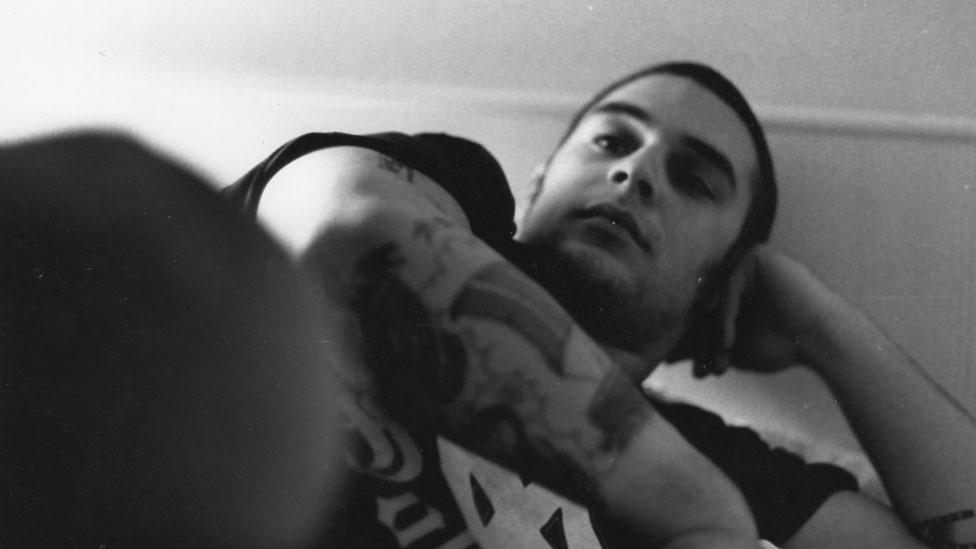

The neo-Nazi uniform of shaved head, boots and tattoos further cemented this sense of belonging.

Initially, Picciolini hid his involvement from his family, covering up his clothes and throwing his heavy boots out of his bedroom window when he was going out, so as not to raise their suspicions.

But over time he began to antagonise and "punish" his parents for what he felt was their abandonment of him. "Because they were immigrants, it may have been part of the reason why I became so anti-immigrant."

He now understands that he didn't have the maturity to ask why his parents were hardly ever home, and why he wasn't getting the attention he thought he deserved.

Violence soon ran at the heart of Picciolini's life. Older skinheads - some in their 20s - would egg him on to fight and commit violence. He found it exhilarating and it made him feel powerful.

"It was about being aggressive, engaging in street fights to terrorise people and to show strength," Picciolini says. "But mostly it was about flying our flag."

The group wore T-shirts that said things like "White Power" or "White Pride" - the distinction was subtle but important, especially when it came to recruitment, where the idea of "pride" was more appealing. "We wanted to push the idea that there's nothing wrong with being proud of who you are and you should fight for that."

Then something happened that took Picciolini from being a foot soldier to leader of the Chicago Area SkinHeads.

In 1989, Martell was sentenced to 11 years in prison for beating up a 20-year-old woman. She had become a target because she had quit a neo-Nazi group and allegedly had black friends.

Martell and others also destroyed Jewish shop windows and painted swastikas all over Chicago on the anniversary of Kristallnacht, or the Night of Broken Glass, in Nazi Germany - an orchestrated attack on thousands of Jewish homes, businesses and places of worship in which 91 Jewish people lost their lives.

Many members of Cash were caught and sent to prison, while others went on the run.

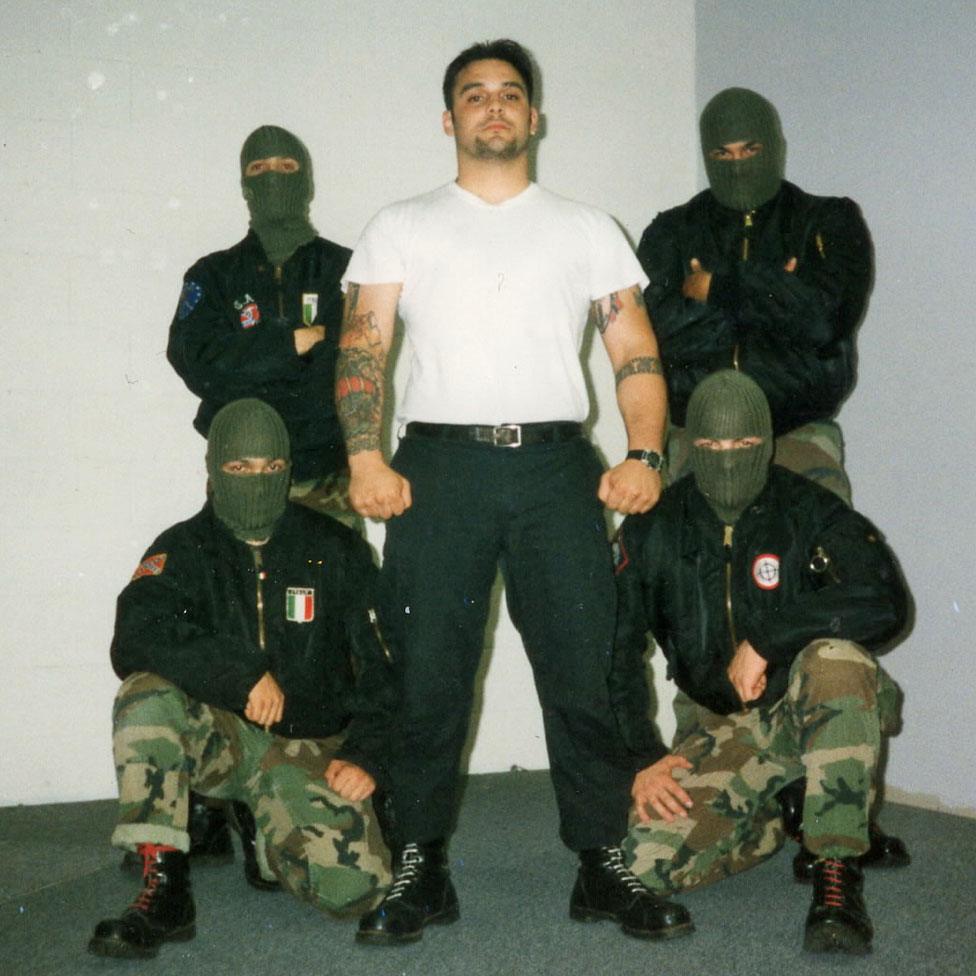

Picciolini, then only 16, was "essentially the last man standing". He took over as leader of his area, and started rebuilding the group.

He ran the operation from an apartment, which he turned into a "Nazi frat boy dorm room", decorated with Nazi flags, Hitler Youth banners and white supremacist posters.

"I was creating propaganda posters, flyers, receiving stickers from other groups around the country and the world. It would also become the command centre for me to begin writing, performing and selling racist music."

He estimates that he recruited around 100 members directly - but indirectly he has no idea of the true scope of his influence. That's because he formed a band, offensively named after the Holocaust, and its music reached far beyond the US.

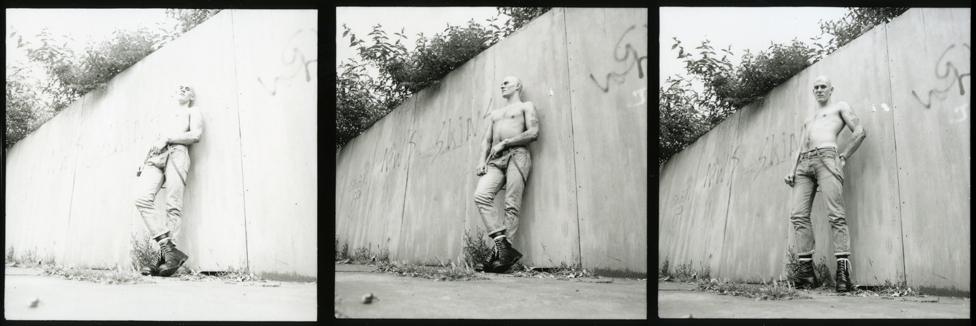

Christian Picciolini and his band on their visit to Germany

The band travelled to Germany to perform, and while he was there, Picciolini even visited Dachau, a concentration camp where tens of thousands of Jewish people were murdered by the Nazis.

"That music lives even today. It still recruits people and may be inspiring acts of violence," says Picciolini, who has spent the past 24 years trying to undo this damage.

"It's horrifying to think that I so blindly believed in something and wasn't able to see how that was hurtful for other people. There's no excuse for that. There's really no way for me to explain the fact that I participated in things that glorified the death of innocent people."

There's one particular violent attack that stays with Picciolini to this day.

When he was 18, after a night of drinking, he and his friends went to McDonald's where some black teenagers were waiting in line for their food.

Drunk and belligerent, Picciolini loudly proclaimed that it was "his" McDonald's and that they needed to leave.

Scared, the teenagers ran out, with Picciolini's group chasing them. As they made their way across the street, one of them pulled out a gun and aimed it at Picciolini and his friends. A shot was fired - missing its target - before the gun jammed. Picciolini jumped on the shooter.

"I remember beating him, kicking him, punching him until his face was swollen. And I remember him on the ground looking up at me through swollen eyes as I was kicking him.

"His eyes were pleading with mine to stay alive."

For the first time, something inside Picciolini shifted.

"I thought for a second that that could be my brother, or somebody that I loved. And I recognised how what I was doing to him not only put him in pain, but would also impact his family and the people that he loved."

In spite of this moment of empathy and connection, however, Picciolini continued to be a member of the Chicago Area SkinHeads for another five years. He says he wasn't brave enough to leave the gang that had given him an identity from the age of 14.

"I was afraid to go back to the nothingness that I had before. I was afraid to be worthless. And I thought that when I was getting this attention, and causing this level of fear, that I was getting respect."

He now realises respect had nothing to do with it, but it took a series of significant encounters with the very people he was being taught to hate, to open his eyes.

Picciolini got married when he was 19 and had two children by the time he was 21.

He says his wife was kind and progressive, and hated the fact that he was involved in the white supremacist movement.

At home with his family, Picciolini says he was a different person.

"I didn't want to recruit my wife and my children. I inherently knew how bad, how dangerous and how violent it was, and I didn't want them to to be involved or associated with it," he says.

As he needed to support his family, he opened a small record shop that sold his own music, and records he imported from Europe.

He knew that he couldn't just walk into City Hall and apply for a business licence to sell Nazi music, so he told them that he would sell a wide variety of music, from punk rock to heavy metal and hip-hop - and he did. But racist music made up about 75% of his revenue.

"What I didn't expect was that people of colour, people who were gay, people who were Jewish would also come into my store," Picciolini says.

He now knows that they didn't wander in by accident. Picciolini was very visible as a white supremacist, and people knew what he was doing and what he was selling.

"These people would come in to challenge me, but they chose to do so through compassion instead of aggression. I'm very grateful for that because it allowed me for the first time to meaningfully interact with the people that I thought I hated."

This personal contact proved to be vitally important for Picciolini.

He particularly remembers a conversation with a black teenage customer who would always ask lots of questions about the music he was selling. He would "goof off and be very funny", Picciolini says.

"One day he came in, and he was visibly upset. He wasn't the happy-go-lucky teen that he normally was. I asked him what was wrong, and he told me that his mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer that morning."

Picciolini's own mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer not long before. Suddenly, he was able to relate, and found himself momentarily forgetting his racist beliefs. They had a deep conversation about life and love and the things they held dear.

Over time, such experiences became more frequent, as Picciolini started to connect with the very people that he had previously believed he needed to keep out of his life.

"It was those people who chose to treat me with compassion, when I least deserved it, that had the most powerful transformative effect on me. Meeting on a fundamental human level is still the most powerful thing that I've seen break hate," he says.

By the time he was 22, Picciolini's marriage had broken down.

"I failed to prioritise my family over the movement. And she eventually left me."

This was the catalyst that finally led Picciolini to close the record store and walk away from white supremacy.

"I wish I could tell you it was a big denouncement, but it wasn't. I faded away. I handed over leadership to somebody else. I used the excuse of needing to work on my family and finding a job and then I would be back. I never intended to go back, I just wasn't brave enough at that point to tell them."

It was only now that he was finally able to look back and see how he'd hurt both strangers and the people closest to him.

"At the centre of the chaos, it was impossible to see an escape. It was impossible to see anything but what I was involved in.

"But the minute I was able to get a little bit of space, the minute I was able to reflect, it came crashing down on me, the weight of what I had done," Picciolini says.

For nearly five years, he tried to hide from his past. He tried to make new friends and get a job without revealing who he had been before.

But by 1999, he was experiencing severe depression - unsure of who he was, where he belonged, or what his purpose was. All he knew was that he wanted to be a better person.

"I was waking up every morning wishing that I hadn't," says Picciolini.

Then one day, one of his few friends came to visit.

"Listen, I don't want to see you die," she told him, and encouraged him to apply for a job at IBM, where she had recently started working.

"I thought she was crazy. Here's this Fortune 100 blue chip technology company, and she wanted me to apply as somebody who was an ex-Nazi, who had been kicked out of six high schools, who didn't even own a computer and hadn't gone to university. But I humoured her. She was a friend and I didn't have very many at the time, and I promised her I would go for this job interview."

Picciolini applied, and was offered an entry level position installing computers at universities and businesses.

It was the first thing in a very long time that had given him some hope, and he was thrilled - until he found out his first day of work would be at one of the schools he'd been kicked out of for fighting, protesting and trying to start a white student union.

"I was terrified. I thought this new hope that I'd felt was over. It would come crashing down the minute somebody recognised me."

On his first day, as he skulked around the corridors, trying to avoid being recognised, John Holmes, the head of security, walked straight past him.

He didn't recognise the former student, but Picciolini had never forgotten Holmes. As a teenager, he had taken particular pleasure in antagonising the black security guard. Now, the feeling that he should try to make amends triumphed over his fear of being noticed.

Picciolini followed Holmes to his car in the school parking lot, and tapped him on the shoulder.

"He turned around and jumped back when he recognised me. He was afraid," Picciolini says.

Unsure of what to do, Piccioloni extended his hand and said, "I'm sorry." Holmes shook it and thanked him for the apology, but said that if he really meant it, he would need to do more.

The two men sat and talked. Picciolini shared his experiences and told him that he had left the movement. Holmes embraced him, and made him promise that he would continue to tell his story.

This was another hugely pivotal moment for Picciolini. It helped him to understand that running away from his past wasn't an option - he needed to find a way to repair some of the damage he had caused, and seek forgiveness from those he had hurt.

"Frankly, Holmes saved my life that day because I'm not sure without his guidance, encouragement and forgiveness, I would have found enough courage to do it on my own," Picciolini says.

At first, he wasn't really sure what to do. Then, not too long afterwards, Picciolini was walking through the mall when a man stopped him and said: "Hey, bro, nice tattoo, White Power!" He had recognised the Nordic runes that were tattooed on Picciolini's forearm. To most people, these aren't obviously hateful symbols, but they have been co-opted by white supremacists and white nationalists.

That became Picciolini's first unofficial intervention. It was the first time since leaving that he had spoken to somebody who was still in the movement.

After a short conversation, it appeared the man understood why he had left, and most importantly, that there was a route for him to leave if he wanted to.

"I don't know that he did, but it left me really thinking that maybe sharing my experiences more widely could help other people understand that there was a path out."

So Picciolini started sharing his stories with people who were still involved in extremist movements, to try to convince them to leave.

In the years since he left he has spoken to over 1,000 people, and believes he has successfully helped almost 400 people disengage from extremist groups across the ideological spectrum, from white nationalists to foreign fighters who travelled to Syria to join Islamic State.

Christian Picciolini now shares his story to explain how and why people can be recruited into extremism

"What leads people to those movements is not the ideology," he argues. "The ideology is simply the final component that gives them permission to be angry."

Instead, he believes that it is life's "potholes" - incidents of trauma or neglect that trip people up - that lead them to join extremist fringes while they search for an identity, community and purpose.

"So when I engage with people to help them to leave these movements, I never debate them ideologically. I don't tell them that their ideas are wrong, even though of course, I know that they are. But what I do is I listen, and I listen for those potholes so that I can find ways to fill them in."

The comedian Sarah Silverman recently spoke about Christian Picciolini in a viral tweet, arguing that redemption must be possible (warning, strong language).

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But he is all too aware that his past actions are still causing harm.

Speaking to a journalist two years ago, Picciolini learned that the white supremacist Dylann Roof, who shot and murdered nine people in a racist attack on a church in Charleston in 2015, had been a fan of the music he'd made many years before.

Four months before the shooting, Roof had posted on a white supremacist website that he'd just seen a documentary about skinheads and was interested in the band performing. He typed out the lyrics for the song, and was asking for more information about them.

When the journalist showed him those lyrics Picciolini realised with horror that he had written them.

"I was devastated to learn that I might have had some influence, or maybe even a major influence, in what he did. He walked into a house of worship, and murdered nine people who he felt were subhuman, who in my lyrics I talked about as destroying our country."

As well as Picciolini's music, Roof was influenced by far-right websites which promoted completely fabricated statistics on black-on-white crime.

"Like those statistics, my songs also promoted the idea that blacks were responsible for all the crime in America and all the rape. Those were the ideas that he took into that church and used to murder nine innocent people, and I feel very responsible for that."

Picciolini knows that there's no way that he can take back the lyrics that inspired people to hate, to hurt, and even to kill. But he is committed to exposing the racist lies he once believed, and trying to prevent others from going down the same path.

"There's nothing that I could say or do that can take away the pain that I caused.

"My goal in the future, aside from going into the communities that I've hurt to try and repair the damage that I've done, is to eliminate any more damage from happening with future generations."

Listen to Christian Picciolini on Outlook on the BBC World Service (producer Alice Gioia)

His new book Breaking Hate: Confronting the New Culture of Extremism is available now.

From the archives

He was the British extreme right's most feared streetfighter. But almost right up to his death, Nicky Crane led a precarious dual existence - until it fell dramatically apart.