100,000 Covid deaths: ‘I cursed the sterile white room where Ann died’

- Published

Already 100,000 people in the UK have died with Covid, according to the official count. The idea of 100,000 deaths is hard for many of us to comprehend. But each was a human being who lived and loved in their own unique way. This is the story of one of them.

By 3:01am, alone in a hospital room, Ann Fitzgerald reached for her phone. This would be her last chance to contact her husband of four decades, the man she'd raised two children with, her Tony - to Ann, he was always her Tony.

The couple had made a pact. So long as Ann was in hospital with Covid, Tony would spend his nights dozing upright in a chair at their bungalow in Pewfall, Merseyside. That way, he would wake up if there was a message alert.

It wasn't much of a sacrifice, Tony thought, not when the woman he'd loved for 47 years was all by herself and frightened. And besides, each time his phone bleeped Tony would know she was still alive, and silently he'd thank the stars.

And so in the early hours of Tuesday 7 April, Ann's last message arrived. She'd summoned the energy to take a farewell selfie as she lay in bed wearing an oxygen mask. "She must have thought: 'Here's something so you won't forget me,'" says Tony.

Two-and-a-half hours later, Ann was dead. She was 65, a mother, a wife, a neighbour, a colleague and a friend, and one of 999 people, external in the UK who died that day with the novel coronavirus.

Soon after the hospital rang and told Tony of her death, he was at her bedside, dressed from head to toe in PPE. No visitors had been allowed to see her while she was alive, but now she was gone it was apparently fine - for reasons he didn't understand.

Tony wept as he apologised to his wife's lifeless body for letting her go like this, with no loved ones by her side. Then he turned and cursed the sterile white hospital ceiling and walls, because they'd been with her at the end and he hadn't.

Back then, few could have imagined the UK's death toll would reach 100,000, or anything close to it.

At that point, the tally stood at 10,000; three weeks previously the UK government's Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance had said limiting the final figure to twice that sum would be a "good outcome".

Now, 10 months on, the total number of people in the UK who have died within 28 days of a coronavirus diagnosis has increased tenfold, while UK excess deaths in 2020 were at their highest level since World War Two. The UK has had one of the highest rates of recorded coronavirus deaths in the world so far.

By any measure, 100,000 is a devastating amount, roughly equivalent to two Premier League football grounds, or the number of people who attend the Reading festival every year. For many people, the sheer scale of loss conveyed by the figure will be impossible to grasp.

"Numbers with lots of zeros are very difficult to interpret, and can be made to look large or small," says Sir David Spiegelhalter, a statistician at the University of Cambridge.

"If I say that 100,000 deaths is two months' worth of normal mortality, then it may not look so bad. If I say that it is more than all the [UK] civilian deaths in WW2, or as if everyone in a city the size of Durham got killed, then it sounds worse. It is challenging to adequately convey such a large number of individual tragedies."

But while many may have become numb to the daily death figures, behind every statistic is a real life lost - a real life like Ann's. "That is why this arbitrary numerical milestone is important," says Hetan Shah, chief executive of the British Academy and a former executive director of the Royal Statistical Society. "It is a chance to reflect again on the terrible toll this pandemic has taken on so many British families."

In a Manchester nightclub one evening in 1973, 18-year-old Tony felt a tap on his arm. It was Ann, a year his senior, whom he knew by sight as a barmaid in one of the city-centre pubs he sometimes drank in. She'd always stood out to him, with her olive skin and striking good looks, but he'd never dared imagine she might be interested in him romantically.

"I'm here with that fella over there," she told him, gesturing towards across the room. "But I don't like him and I don't know what to do."

Tony walked over to Ann's date and told him to clear off. Then Tony returned to Ann, and the two of them had a drink together, and then another. Before long they were a couple and Tony decided he was the luckiest man in the world.

Soon he learned all about Ann's background. Her Lithuanian-born Jewish father had died when she was two years old, and with her mother unable to cope she'd been passed between relatives throughout her childhood. By 16 she was living in a bedsit, supporting herself with waitressing and bar work - she'd also been employed at the legendary art-deco Kardoma café on Market Street and at George Best's nightclub, Oscar's.

"As a consequence of her upbringing she was really, really independent," says Tony. "She was really good at talking to people, and she was sharp - the sharpest, wittiest person I've ever met."

They rented a flat in Fallowfield together and made it their home. After Ann was offered relief work running bars around Manchester, Tony quit his job as a sales rep to join her. Eventually, in 1981, they took on their own pub. It was in what was then a tough part of Salford, but Ann had grown up nearby and knew how to handle the local characters: "She could have you in stitches, but she could throw you a look, and you knew you had to behave yourself," Tony says.

The couple were offered the chance to take on another pub in Sale Moor. They thought they were going upmarket, but it turned out to be quite the reverse; Tony would joke that he should take away all the tables and chairs and install a boxing ring instead.

But Ann wasn't intimidated by anyone. According to Tony, when a notorious local villain turned up and demanded a free drink, Ann stood her ground: "My husband's name is above the front door, and he pays for his drinks, so you're going to pay for yours," she told him. Impressed, the villain ended up buying one for Ann instead.

She and Tony knew it was time to quit when burglars broke in one night while their baby daughter slept in her cot upstairs. Tony went back on the road as a salesman; Ann worked variously as a debt counsellor, an incident manager for the RAC, and a sales trainer at a cotton firm. Their children, Gary, and Rachel, never once heard them argue, Tony says.

For six years the couple had a stall at Altrincham Market selling women's clothes. "People would come, not necessarily to buy something - they just wanted to see Ann," says Tony. "And as a consequence, they'd buy something they didn't really want." Each time this happened, Ann would give Tony a wink.

By the start of 2020, Ann and Tony were looking forward to a long retirement together. Both their children had left home, and they'd recently moved to the bungalow. The news broadcasts had begun describing a deadly pandemic that had spread from China. But Ann wasn't leaving the house much while she recovered from an operation to replace both hips.

Then one Thursday in March she went for a haircut; she asked for the colour to be darkened slightly too, and when he first saw her afterwards Tony told her how much he loved it. Ann mentioned that the hairdresser had been coughing.

Three days later, Ann began coughing too, and soon afterwards so did Tony. But with a fever, she felt worse, and within a few more days she was barely able to stand. She asked Tony to call 999.

The paramedics helped her to the ambulance. It haunts Tony now that he didn't hug or kiss her as they said goodbye. "Neither of us thought for one moment that it would be the last day I would ever see her alive," he says. She told him they'd probably give her antibiotics and he could come and pick her up in a few hours.

But later that day she phoned him to say the doctors suspected Covid and they would be keeping her in. As in many hospitals during the first wave, no visiting was allowed.

Tony could only stay in touch with her by phone. When a doctor told him the next 24 hours were critical, he didn't tell Ann, because he knew how scared she was already by then.

But he did pass on something else the medic had said - that they were deeply impressed by her upbeat attitude and fighting spirit. Tony told her, too, that he believed she would be home soon: "I had to say that to keep her fighting, and fight she did for 10 days."

The last time they spoke was Saturday 4 April. Ann told Tony she thought she'd turned a corner; she'd eaten a sandwich and some yoghurt. After that, talking became too difficult for her; she wasn't in intensive care but the mask she wore to help her breathe was getting in the way.

Three days after their last conversation, Tony was sitting in a white hospital room beside Ann's body. He sat with her there for an hour. He didn't just apologise, he also promised he'd make sure she was remembered properly. When it was time to leave, a nurse gave him a booklet about bereavement and a black bag in which to put Ann's belongings. Tony carried them along a hospital corridor, wondering how he would tell Gary and Rachel their mum was dead.

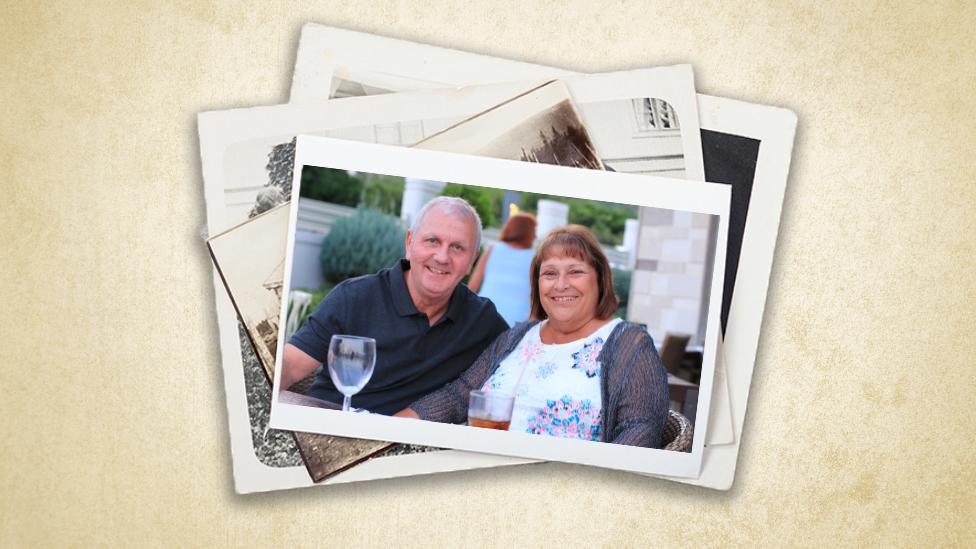

There are eight photographs of Ann in Tony's living room. In each of them she looks full of joy. "Every time I look around, there's a picture of Ann somewhere," Tony says. "She's smiling and I'm thinking, 'If only I could turn back the clock.' But I can't, you know, and nor can all those other families and relations, either."

Nearly 10 months after Ann's death, Tony finds himself resenting the home he's been left alone inside. If they hadn't moved there, he reasons, Ann wouldn't have gone to that hairdresser's that day and caught the virus - she'd still be alive, perhaps.

He feels robbed of the 20 additional years he hoped they'd spend together, as surely will thousands of other bereaved relatives. While the impact on the very oldest has been widely recognised, those who might have looked forward to a long retirement have been badly hit, too - during the pandemic, around 15% of all UK fatalities with Covid mentioned on the death certificate have been among those aged 65-74.

Tony desperately wishes his life would go back to how it was, but knows it won't.

Ann's funeral didn't give him any closure. Tony would rather she had been buried, but the undertaker warned him to hurry - extra restrictions could be introduced any time - so he took the date that was offered by the crematorium.

As it was, under the rules that were already in force, only 10 mourners were permitted, spaced out around the chapel. No flowers or photographs on display, no hugging.

Tony understood why all this was necessary - but it wasn't the celebration of Ann's bright, gregarious, love-filled life that he thought she deserved. He'd have to plan another one when all this was over.

As the months went on, Tony joined online Covid support groups. It helped talking to others who understood how it felt to have lost someone. There was the family of a 19-year-old boy. A woman who was mourning both her mum and her dad. Another woman whose husband had died in the car as she drove him to hospital.

He thought of these stories each time he switched on the news and watched the Covid mortality figures climb higher and higher. Behind these cold statistics were human lives. And each was as unique as Ann, with a personality and backstory entirely of their own.

It would have been Ann and Tony's 41st wedding anniversary on 6 October, the day before the six-month anniversary of her death. The following month, a few days after the UK's Covid death toll reached 50,000, Tony once again felt Ann's absence bitterly on what would have been her 66th birthday.

"Christmas was a nightmare for me," he says. Under the rules for the festive season, Gary and Rachel and their partners were able to be there with him, and cooking lunch kept him busy most of the day. But afterwards, when he was on his own again, the reality hit that another celebration had gone by without Ann beside him, and Tony sat down and sobbed.

For millions the arrival of the Covid vaccines has brought hope, but it is a cold comfort for those who have lost someone. If every one of the 100,000 were loved by a dozen people, "that's a million people in Britain who have been bereaved", says the bioethicist and sociologist Prof Sir Tom Shakespeare. "We need a national monument, some form of remembering."

Tony is not one of those who will find it hard to grasp the significance of this bleak milestone.

"To me it's 100,000 poor souls fighting for breath, and they've not had a hug from anyone in their family," he says. "There's a name - there's a person behind that number. And then they've passed away, and the family goes through the grief that I've been through - the numbness, the shock, the anguish and the pain to come."

Follow @mrjonkelly, external on Twitter

Picture editor: Emma Lynch. Additional reporting by Oliver Barnes