The UK professor and the fake Russian agent

- Published

Professor Paul McKeigue

A British professor corresponded for months with a man called only "Ivan", seeking assistance to discredit an organisation that helps bring Syrian war criminals to justice. He also asked "Ivan" to investigate other British academics and journalists. The email exchange, seen by the BBC, reveals how, a decade on from the start of the Syrian conflict, a battle is still being waged in the field of information and misinformation.

One chilly December morning there was a ping as an email from a professor at Edinburgh University dropped into Bill Wiley's inbox. The subject line read: Questions for William Wiley.

Wiley, who runs an organisation that salvages documents for use in war crimes trials from abandoned Syrian government buildings, recognised the sender's name.

Prof Paul McKeigue, an epidemiologist from Edinburgh University, had been in touch once before asking similar questions about Wiley's NGO - the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (Cija) - for a critical report he was writing with a professor from Bristol and a former professor who once taught at Sheffield.

Knowing what he did of McKeigue's view that Western-funded NGOs are acting on behalf of the CIA and MI6 to blacken the image of the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, Wiley felt sure their report would accuse Cija of distorting the truth about torture and murder in Syrian jails.

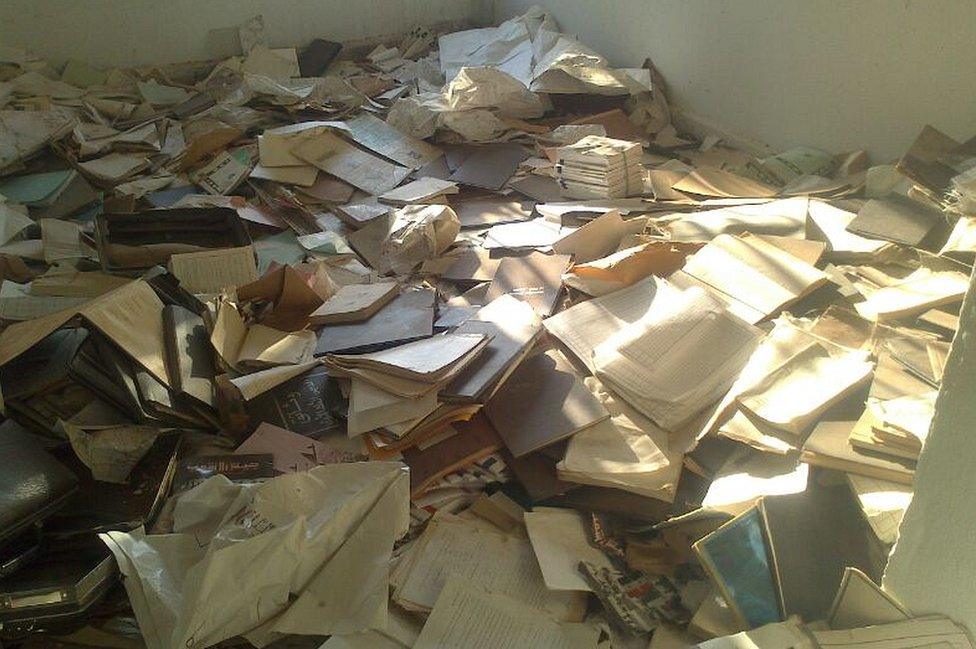

Over the last decade Cija's undercover investigators have salvaged more than 1.3 million documents created by a bureaucratic regime that is obsessed with paperwork, even when it concerns the brutal killing of its own people. All that paperwork is being held in an archive at Cija's headquarters in a secret location in Europe.

McKeigue's email to Wiley repeated that he and his colleagues were investigating Cija, but he didn't ask questions about Cija's work. He only seemed to be interested in companies Wiley had registered in his name.

Wiley didn't reply.

Bill Wiley and some of the 1.3 million documents in the Cija archive

A few hours later, McKeigue received an unexpected email too. It was from an anonymous sender and it read: "My office heard from London yesterday that you have some questions about Syria. Perhaps we can help you get to the truth."

McKeigue quickly replied with a few questions to test his new acquaintance. Was this person aware of chemical attacks in Syria that had been faked?

He certainly was, and he hinted that he had access to a treasure trove of knowledge. McKeigue seemed excited to have a fresh source, and an email exchange that would last more than three months got under way.

Early on McKeigue revealed that he was interested in Cija and particularly in Wiley. The reply came back that Wiley was a CIA operative who had worked in the US embassy in Iraq. (Part of this was true, Wiley, a Canadian, had been employed by the US Department of Defense to work on the trial of Saddam Hussein in Iraq - but he says he has never worked for the intelligence services.)

McKeigue was cautious, though.

"If we just come straight out with 'Wiley is CIA,' I think we will be derided as conspiracy theorists making wild unsourced allegations," he wrote.

His contact replied: "My colleagues laughed in a knowing way when this was read to them. What sort of evidence would you want to feel comfortable stating this fact? If we can provide it without damage to our sources we will do that."

While McKeigue's email sign-off included a link to his Edinburgh University profile, his new correspondent initially left his emails unsigned. The only clues to his identity were occasional mistakes in his English, and references to his headquarters in Moscow.

And then, after a while, he began signing himself "Ivan".

Documents strewn across a room in abandoned Baath Party offices in northern Syria, September 2013

McKeigue says he kept an open mind about who was on the other end of this correspondence. He told me that like any other journalist or citizen investigator, he cultivates contacts with all kinds of people who may have relevant information, including anonymous sources. He also told me he believed it was entirely legal for him to do this as a private citizen without access to state secrets.

Some of the correspondence dealt with McKeigue's theories about Cija's activities. The academic explained that he and his colleagues regarded Cija as part of a "strategic communications" - or StratCom - operation run by the CIA and MI6 on behalf of their governments, which were hell bent on regime change in Syria.

From the emails it seems that McKeigue really believed he was doing a public service by trying to uncover a conspiracy being waged to dupe the public.

But he also asked Ivan for personal information about Wiley - about a woman he might have slept with, and whether he had a cocaine habit - which didn't bear any relation to the trustworthiness of Cija's documents.

And he kept returning to questions about Cija's finances. His overarching aim, he explained, was to get people questioning the evidence Cija had gathered, but there were different ways of doing this, he noted.

"We call it the Al Capone tactic - even if we can't bring them down over war crimes, we may be able to get them over fraud."

This was why his questions to Wiley had focused on the companies he had started.

The European anti-fraud office, Olaf, has accused Cija of fraud and irregular accounting, relating to a contract it received from the EU in 2013 worth 3m euros (£2.6m). The European Commission is still looking into Olaf's report, but Commission spokesman Peter Stano told the BBC this was not a reason to question the importance of Cija's evidence.

"The Olaf investigation concerns invoicing by the consortium, not the information collected during the implementation of the project and there is no indication of wrongdoing concerning the deliverables of the project," he said.

Cija's finance team reject the Olaf allegations and say they have sent the European Commission documentation proving that they are false. They also say that since 2013 the organisation has received 70 grants totalling more than 42m euros (£36m), and been audited 64 times by external auditors without any adverse findings.

Cija has obtained voluminous evidence of war crimes carried out in Syria

"Ivan" encouraged the professor in his investigations and praised his ingenuity.

"We note that this exchange remains a pleasure for our office. Thank you again and again for your important work... Thank you for resisting the UK's anti-Russia operations. This means a lot to us," he wrote.

Paul McKeigue says the co-authors of his investigation into Cija did not know about his relationship with Ivan, but the information the professor was gathering was meant for their joint paper. He outlined their motivation: "A key objective of our little academic group is to encourage members of parliament, lawyers and journalists to hold the government to account by asking questions about these StratCom activities that have not only drawn the UK into confrontation with other countries but have also been used to marginalise and smear dissenters at home."

Before long Ivan was giving McKeigue direction, asking him for information, telling him who to speak to and who not to approach, and the professor seemed to comply with some of these requests. Six weeks into the correspondence Prof McKeigue agreed not to write to any Cija employees without Ivan's prior approval.

"I will not contact anyone without checking first with you," he wrote.

McKeigue forwarded emails and information to Ivan at his request.

Then the professor wrote to Ivan with big news. He had stumbled across what he seemed to regard as persuasive evidence that Wiley was a CIA agent during the time he was in Iraq. It came in a book by a former CIA analyst, John Nixon, who described briefing US Vice-President Dick Cheney on Saddam's interrogation, in April 2008.

"He went to Cheney's office with 'Bill, the CIA analyst who had succeeded me in Baghdad'," McKeigue writes, quoting Nixon's book. "This can only be Wiley. What do you think? The CIA's Publication Review Board redacted many other passages, but missed this."

It didn't seem to occur to McKeigue that there could have been more than one "Bill" in Iraq at the time, or that Nixon might have used a false name. But Ivan was impressed.

"This is why we admire you and your work so much!!... Funny, we did not know that the meeting was in the public. We thought it was our secret!"

McKeigue seemed excited to be getting somewhere. Now he returned to an offer of £10,000 Ivan had made, which he had originally declined. Perhaps it would be useful after all, he said, to bring a legal case against Bill Wiley and Cija on behalf of their employees, who had been "deceived into working for a CIA front organisation".

"Such a lawsuit would be expensive… Injecting money into a legal fund, covering past and future costs, might be a way for your office to contribute. But the scale of support required would be far more than the figure you mention."

McKeigue also cast his net wider than Cija and asked Ivan to look into what he called "the UK network of Syria narrative enforcers". These included British academics and journalists who have challenged his writings about Syria. McKeigue sent Ivan a long list of names and email addresses, and asked him to use that information to work out the connections between them, and who was co-ordinating them.

Chloe Hadjimatheou was among the journalists McKeigue asked "Ivan" to investigate

McKeigue told the man hinting he was a Russian spy that he had particular concerns about a BBC producer who covers Syria.

"Does your office know anything about him?" he asked. "It's clear to us that he has been involved in staging incidents in Syria since 2013."

The professor does not seem concerned about whether making an allegation of this kind to a possible Russian agent might put the producer in danger.

McKeigue told me that all the information he passed on to Ivan, including email addresses, was in the public domain. He also said the role of these individuals as leading communicators in "the UK-led information operations associated with the Syrian conflict" had been widely described in the media.

My name was also included on McKeigue's list of these "narrative enforcers" supposedly co-ordinated by the British government, and he didn't hold back in telling Ivan what he thinks of me.

"We know quite a lot about CH [Chloe Hadjimatheou], and think she's just a dim-witted person who has been flattered into taking on something beyond her competence."

But Ivan was not a Russian agent - he did not exist. His emails were written by a team of Cija employees, assembled by Bill Wiley in an urgent effort to find out how much McKeigue knew about his organisation.

He was particularly worried about the possibility that a Cija employee who had been sacked might have approached McKeigue and his co-authors and given away the location of the archive and the names of staff.

Only three staff members of Cija have made their names public, for good reason, says Wiley. They could be harassed or threatened, and hostile elements might find it easier to get into Cija's systems if they knew the names of employees. And the Syrian regime had good reasons to want to destroy the archive of documents.

In the course of the correspondence, McKeigue wrote that the sacked member of staff had indeed spoken to him, offering this information and other personal details about Wiley.

McKeigue told the BBC that although he did plan on revealing the location of the office he had no intention of making the more personal information public.

But Wiley didn't know this, and meanwhile he was well aware that McKeigue's close contacts include the Damascus-based British blogger, Vanessa Beeley.

Beeley extols the virtues of the Syrian army as well as President Bashar al-Assad and his wife, often posting photographs of herself with members of the Syrian regime and military commanders on social media.

Wiley says he fears that anything McKeigue knows he may have told Beeley, and that she may have passed it on to the Syrian state. So he is not taking any risks. He is currently making plans to relocate the entire Cija archive and staff, and to uproot his family too.

The sacked Cija staff member says she would never deliberately compromise the security of ex-colleagues or their families and does not believe she has done so.

Both McKeigue and Beeley are members of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, a group of "independent researchers" and academics many of whom share McKeigue's view that British and US intelligence services are using the media to cast the Syrian government in a negative light, in order to make the case for regime change.

I discussed the Working Group in my Mayday podcast which traces the life and death of James Le Mesurier, a former British army officer, and co-founder of the White Helmets - a group of ordinary Syrian civilians trained with the help of Western funding in how to rescue survivors from bombed buildings. The email exchange between McKeigue and "Ivan" is the subject of a 12th episode of the podcast, which will be published on 6 April.

It was thanks to this podcast that I ended up on McKeigue's blacklist of journalists. "From the Mayday podcasts it is clear that you are working with... a presumed MI6 officer," he wrote to me.

One of the themes of Mayday was how the White Helmets found themselves at the centre of a battle to control the narrative of the Syrian war.

The Go-Pro cameras attached to their helmets provided footage showing how civilian areas, hospitals and schools were being bombed by Syrian and Russian aircraft. These videos, posted on social media, made it into news reports and documentaries making the group famous and providing millions with evidence of war crimes, including the aftermath of chemical attacks.

As a result, James Le Mesurier and the White Helmets came under attack from the Russian and Syrian states, which accused the organisation of everything from working with jihadists to overseeing an organ-harvesting racket. These ideas were taken up by some in the West.

One of Paul McKeigue's main preoccupations has been the supposed faking of chemical attacks. Through the Working Group he has co-authored papers, for example, suggesting that the Syrian regime might not have been responsible for the 2018 chlorine attack on the town of Douma as inspectors for the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) concluded. Instead, he has put forward the idea that more than 40 victims might have been deliberately killed in a gas chamber as part of a "managed massacre" by rebel forces with the help of the White Helmets in an elaborate scheme to con the world.

Children being treated after the suspected chemical attack in Douma

This was a theory he outlined in a talk presented by the Working Group in Westminster last year. The head of the Intelligence Security Committee, Conservative MP Dr Julian Lewis, was there, although he says he arrived late and didn't hear the part about gas chambers.

It turns out McKeigue borrowed the gas chamber idea from a retired American pharmacologist, Denis O'Brien, who described in a self-published paper how it had come to him in a dream after he had eaten an anchovy pizza. O'Brien's paper is full of assumption and conjecture and his analysis is based on his own dream and grainy photographs. His other pet project was something he called "New Jews" a list of "Mainstream Media owners, operators, and stars" with Jewish connections.

McKeigue told me he didn't believe O'Brien's personal views negated the "compelling" evidence his paper offers for the idea that chemical attacks were staged using gas chambers. He didn't mention the anchovy-fuelled dreams but he did say that he is neutral with respect to the Syrian conflict, and that his objective is to expose the covert information operations that have, in his view, "subverted our system of parliamentary government".

The Working Group has echoed other Russian disinformation narratives too. In 2018 McKeigue and the two co-authors of his report on Cija - Piers Robinson, a former professor at the University of Sheffield, and David Miller a professor at Bristol University - published a series of papers on the Salisbury attacks. These argued that the US and UK had had a motive to kill the Russian dissident, Sergei Skripal, in order to prevent him from testifying in a libel case against Christopher Steele, the man who compiled the infamous dossier that purported to show co-operation between the Trump campaign and Russia in the run up to the 2016 US election.

Despite the extensive evidence found by the UK authorities pointing to the involvement of the Russian government, and of two assassins believed to have been working for the Russian security services, the group hypothesised at great length about various factors that would cast doubt on Russia's involvement in the poisonings.

Two professors and a former professor

In his day job, Prof Paul McKeigue is a genetic epidemiologist. For the last year he has been writing papers about the coronavirus pandemic and acting as a consultant to Public Health Scotland. In October 2020 he became an advocate for the Great Barrington Declaration, which called for the national lockdown to be replaced by the isolation of vulnerable people, allowing the rest of the population to develop herd immunity.

Prof David Miller, a sociologist at Bristol University, is currently at the centre of a row over comments he made about Israel and Jewish students. He has long argued that a network of Zionist organisations in the UK, funded and controlled by Israel, has been stirring up Islamophobia. His recent comments included a claim that Israel is "trying to exert its will all over the world".

The founder of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media is Dr Piers Robinson, who was professor of politics, society and political journalism at Sheffield University until his sudden departure in 2019. Before he left he warned students not to buy into stories about fake news, external, which he said were a distraction from the propaganda and lies told by the "mainstream" media. Robinson has argued that the US government may have been behind the 9/11 attacks, and that coronavirus has been hyped to control the population through fear.

McKeigue says the Working Group's report criticises what was then the official line - that only Russia had the technical means and the motive to carry out this attack. He stresses that at no point do they suggest that "Western intelligence services" were responsible for the attack.

In 2019 the Working Group wrote a paper accusing James Le Mesurier of corruption and involvement in faking chemical attacks in Syria. But by 2020 Cija was firmly in its sights.

Evidence gathered by Cija had made it into high profile court cases like the 2018 lawsuit filed against the Syrian regime by the family of Marie Colvin - the American journalist working for The Sunday Times, who was killed in a rocket attack on a makeshift media centre in the rebel-held city of Homs in February 2012.

A Turkish journalist holds images of photographer Remi Ochlik and Marie Colvin both killed in Homs on 22 February 2012

Cija documents were cited extensively in the judgement, which found the Syrian government liable for the extrajudicial killing of Colvin in a deliberate artillery attack, awarding the journalist's family damages of $302m.

Cija has also gathered close to 300,000 documents and other pieces of evidence on the Islamic State group, some of which was submitted as evidence in the successful prosecutions of two of its fighters in Germany and the Netherlands.

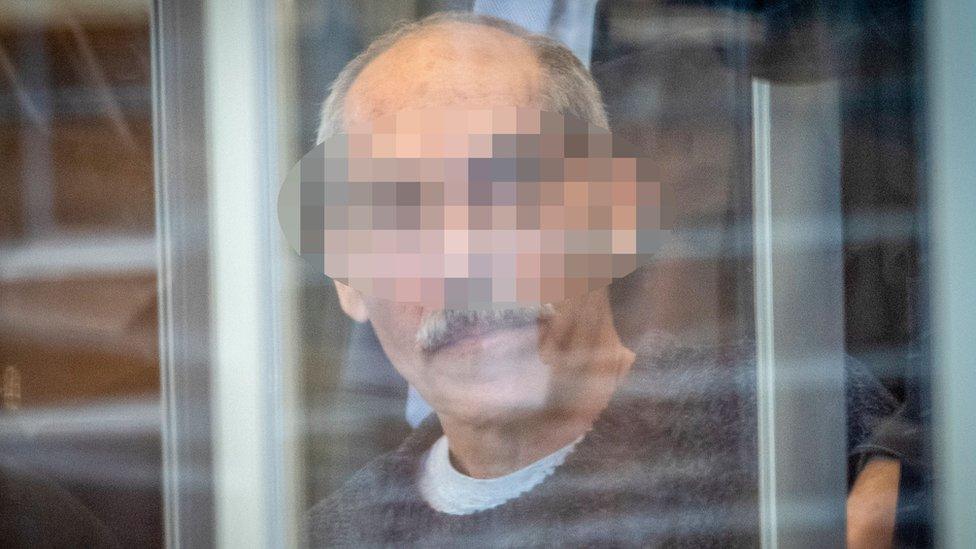

These days Cija is busy with a war crimes trial under way in the German city of Koblenz, one of the first of its kind against a member of the Syrian regime on European soil. In the dock is a former colonel in the Syrian military intelligence service, Anwar Raslan, who stands accused of 4,000 counts of torture, 58 counts of murder and rape and sexual coercion over a period of just 18 months.

For 18 years Raslan was in charge of interrogations at one of Syria's most notorious detention facilities - Branch 251 in central Damascus.

From the outside it's an unremarkable government building, there is a sportswear shop across the road and a supermarket on the next block, but people who make it out alive - which is by no means a given - are marked for life by the terrible torture they've undergone there.

Christoph Reuter, a journalist working for Der Spiegel who interviewed Raslan several years before his arrest, says Raslan was proud of his work and of his success at extracting information.

But when the uprising began in 2011, Raslan told Reuter that he felt professionally humiliated at having to torture people whose only crime was to have been caught at a demonstration. They didn't have any information to be extracted.

"It insulted his professional pride, and insulted his moral standards… he couldn't stand it any more to torture, to have people possibly killed, who clearly had done nothing wrong," says Reuter.

Anwar Raslan, 57, arrives at court in April 2020 - German law forbids publication of identifying photographs

Aided by opposition rebels, who wanted as many high-ranking defections as possible in order to weaken the regime, Raslan defected to Jordan. By 2014 he had received asylum in Germany, where a year later he walked into a Berlin police station saying he was being followed by Syrian intelligence officers. The police were understandably sceptical, so he explained that he was a defector from the regime - which led ultimately to his arrest at the start of 2020.

The trial has provided an incredible insight into the workings of the Syrian regime as witness after witness has taken the stand describing horrific torture, including the systematic rape of men and women.

Raslan denies all the charges and his defence has not yet put its side of the case. A lower-ranking Syrian intelligence service employee who helped arrest protesters who were later tortured and murdered was found guilty by the Koblenz court in February and sentenced to more than four years in prison. If Raslan is found guilty he could spend the rest of his life behind bars.

McKeigue told "Ivan" that he was concerned about the evidence Cija was submitting to the Koblenz trial. He and his co-authors suspected that Cija had originated as a covert UK government strategic communications programme aimed at disseminating false news to discredit President Assad's government and that it might be using its documents to make the Syrian government seem more vicious than it really was.

One of the documents submitted by Cija to the court, in order to paint a picture of the system within which Raslan was working, contains a letter from an official to a detention facility to complain about the torture methods being used, including glass bottles being inserted into people's anal passages. The staff are reminded to use "pre-approved protocols" for interrogation.

A photo taken by Cija at the Raqqa General Intelligence Directorate - one of many sources of documents

Another important document in Cija's possession are the minutes from a 2011 meeting of the so-called Central Crisis Management Cell or CCMC, a committee made up of Syrian ministers, heads of the security and intelligence services and the military. It was a top-level body akin to a war cabinet.

The minutes in Cija's archive show the CCMC discussing and formalising a list of targets who they wanted arrested and detained, including people who participated in protests, people who funded protests, anyone who "besmirched the name of Syria" in comments to the foreign media.

Bill Wiley says that he has collected documentary evidence showing that the CCMC decision was passed through the chain of command unamended all the way down to local security intelligence branches and that it lent a structure and formality to the thousands of arrests that followed. The Syrian president was not present at that particular meeting but the minutes Cija has in its possession were taken to him for his personal signature.

"From a legal point of view, this is quite important because it incorporates the members of the CCMC, who took that decision," explains Wiley.

It is evident, he says, that there was a very conscious decision to arrest unarmed protesters and put them in detention facilities where they would be tortured and possibly killed and that the decision went all the way to the very top of the Syrian regime.

In his emails McKeigue told "Ivan" that he was concerned about the authenticity of this Cija document but also about the evidence being presented to the court by an anonymous defector known by the alias Caesar.

Army defector "Caesar", who began leaking images to Syrian opposition groups in 2011, speaking in Washington DC in 2020

Caesar was a state photographer whose job was to document the dead bodies of torture victims, and who in 2013 defected from Syria with a hard drive containing 53,275 photographs. They show more than 6,000 individual victims, men women and children, who display signs of unimaginable torture, including many who have their eyes gouged out.

Forensic investigators in Europe have examined the photographs and the metadata they contain and pronounced them genuine. Wiley's team in Syria has also found documents that detail where individual prisoners shown in Caesar's pictures were held - each was photographed with a number painted on their skin, or stuck on their body, and the same prisoner numbers are used in Cija documents.

More than 700 victims have been identified by their families after photos were cropped and put online so that relatives could search for missing loved ones.

Stephen Rapp, the former US Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes Issues, and a member of Cija's board, says there is no doubt about the Caesar evidence.

"It's proven rock solid. We've got better evidence on the Syrian regime, frankly, than the prosecutors two generations ago had against the Nazis. The one thing that they didn't have was pictures of each of those individual victims with a card in front of them, identifying the unit that had killed them," he says.

"And so in that sense, when you throw in the Caesar photos, it adds up to better evidence than they had at Nuremberg."

An exhibition of photographs smuggled out of Syria documenting the atrocities carried out by the Assad regime (Washington DC, 2015)

McKeigue seemed far from convinced, though. The Working Group had analysed the Caesar photographs and - according to the emails - decided the victims might be captives executed by opposition groups. With the knowledge that courts across Europe had determined that Caesar's identity needed to be protected, the academic asked Ivan to tell him who Caesar was.

"Do you have any more information about his identity and the Syrian opposition group that he is affiliated with?" he asked.

McKeigue told me he believes the Syrian state knows who Caesar is and so his identity does not need to be protected.

But the identities both of evidence gatherers, like Caesar, and of regime officials who are named in the documents Cija has gathered need to be confidential because, says Bill Wiley, they are at risk of reprisals, not just from the Syrian regime but also from members of the public.

He recounts how, during the televised trial of Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2005, two Iraqi officials were murdered days after their names appeared in a document displayed on a screen in the courtroom.

At times during their correspondence McKeigue appeared to talk remarkably freely with "Ivan".

A couple of months into their exchange the professor claimed that his co-author, Piers Robinson, and the Damascus-based blogger, Vanessa Beeley, could be reached through a Russian diplomat in Geneva, Sergey Krutskikh.

The BBC approached the diplomat for comment, but got no reply.

Vanessa Beeley has always maintained she's independent, not incentivised by any government and that her concern is getting to the truth.

Piers Robinson said that, like all good researchers, during the course of his writing he is in contact with senior government officials, politicians and members of the military from many states.

McKeigue's readiness to expose British academics and journalists to investigation by a man who dropped clues he was a Russian agent, is repeated in some of the later emails with regard to people in far more vulnerable positions.

He drew "Ivan's" attention to a journalist for the Russian state-funded media outlet, Ruptly, who had been employing local journalists in Douma to look into the attack, and who had shared some information about his results in several emails to McKeigue and Piers Robinson.

Douma, on the outskirts of Damascus, at the time of the chemical attack in April 2018

Here was an opportunity to prove that the Douma attack was faked. But things didn't go as they imagined. Ruptly found a witness who said his children and wife had all been killed in the chemical attack.

McKeigue then wrote to Ivan, inviting him to spy on the Ruptly journalist.

"I suggest that your office keeps an eye on what [he] and his stringers (if they exist) are doing, without letting him know that anyone has raised concerns."

McKeigue also shared the entire Ruptly email correspondence. Had "Ivan" been a real agent he would now have had in his possession the details of a Syrian witness whose evidence ran contrary to the national narrative.

Earlier this month the UK government published its Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy in which it mentioned Russia 14 times as posing "the most acute threat to our security".

Asked to comment on McKeigue's correspondence with "Ivan", Edinburgh University said that freedom of expression within the law is central to the concept of a university, and that they seek to foster a culture that enables this kind of expression to take place.

Paul McKeigue declined invitations for an interview but told me in an email that he believed he was the victim of an elaborate entrapment operation.

"I think the effort put into this operation makes it obvious that I have annoyed some state-level actors," he said.

In a statement published on the Working Group's website he said: "The people on the other end of this sting managed to get me to reveal information provided by others that was not intended to be shared, along with other information that may have been embellished. This was a failure on my part for which I accept responsibility and have apologised to those concerned."

Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, the director of the NGO Doctors Under Fire, which campaigns against attacks on hospitals in war zones, reacted angrily when told that McKeigue repeatedly referred to him in emails to "Ivan" as a "known MI6 agent".

"Potentially this guy's putting lots of people's lives [at risk] and potentially one of them is mine," he said.

Approximately 400,000 civilians will be deprived of healthcare after a hospital in Idlib was targeted earlier this week

De Bretton-Gordon says he has never worked for the intelligence services.

Dr Mohammed Idrees Ahmad from Stirling University, one of those whom McKeigue wanted Ivan to gather information on, said he was not surprised by the revelation, as he has come under attack from the Working Group before. He accused them of spreading rumours first that he was working for the CIA, and later that he was employed by MI6.

Bill Wiley says he was forced to carry out the three-month deception because it was the only legal means he could use to work out whether there had been any security breaches which might endanger his staff and the archive.

"This wasn't some kind of revenge operation. It was driven entirely by concerns for our security, and ultimately our findings justified those concerns," he says.

"Aside from protecting our sources, witnesses and our personnel, we need to protect our reputation. Because if our reputation is dragged through the mud, our funding will stop. And if the funding stops that will have a highly negative impact on justice."

Correction 23 April 2021: Vanessa Beeley wasn't invited to respond to this article before publication but has since told the BBC that she has never had any communication with Russian diplomat Sergey Krutskikh. Piers Robinson also says he is not in contact with Sergey Krutskikh.