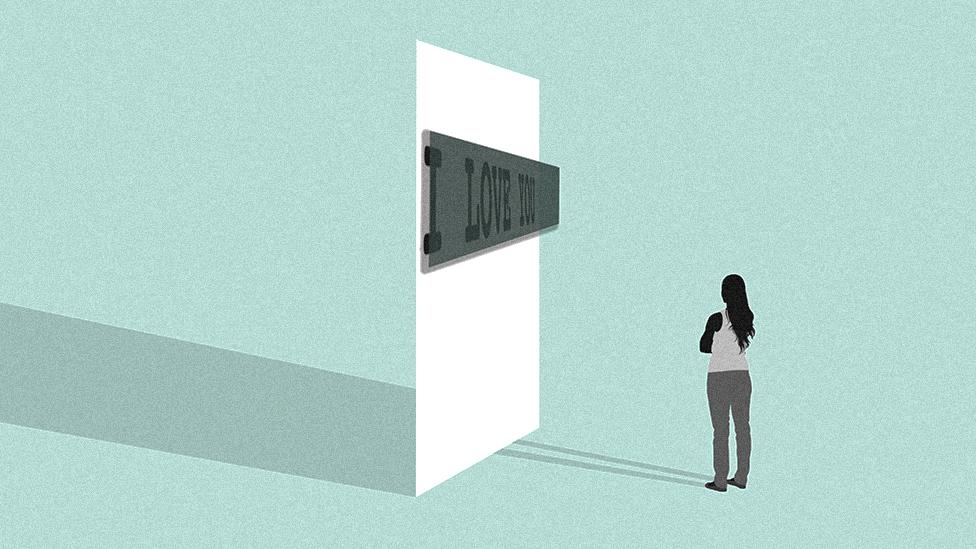

Letterbox contact: ‘Don’t my birth children have a right to know I’m dying?'

- Published

A young woman whose children were adopted wants them to know that she has a terminal illness. But the rules don't permit direct contact, writes Georgina Hewes, so she cannot be sure they have been told.

In 2017, Hanna was told she had six months to live.

"When I got the news, I got straight on the phone to Social Services. I just needed to know my children were OK," she says.

At that point, 11 years after her children had been taken from her, Hanna had had no news of them for seven years.

As a teenage mum who'd been in and out of care and had no support network to speak of, Social Services had deemed Hanna unable to care for her children.

Hanna describes the moment she watched her 14-month-old twins driven away to their new family as "the worst day of my life". She was 16, and had spent more than a year fighting to keep them, while living in a mother and baby foster placement.

"Mum used to beat me up until I was black and blue. I think they worried that history would repeat itself," she says.

Like most birth parents in the UK, Hanna was granted "letterbox contact" when her children were adopted - an agreement meaning she could exchange letters with her children and their adopters until the children reached 18.

In her case, the judge extended the typical once or twice a year letterbox to three times a year, specifying that Hanna should also be allowed to send her children birthday and Christmas cards as well as receive photos from the adopters.

But making arrangements is one thing - maintaining them is something else altogether.

In the end I'd take the photos out and not read the letters, as it was too painful

About a year after her children were gone, true to the "letterbox contact agreement", Hanna received the first of many letters. But rather than uplifting her, it pushed her into a "deeper depression".

"The letter was written as if it had been written by my children, saying 'Mummy and Daddy did this with us, we did that.' But my children were only two, it was clear they hadn't written it."

As time progressed, letters continued to arrive. But Hanna increasingly left them unread. "It was as if they were following a particular template - 'We went on holiday, we went horse-riding.' None of them told me anything I wanted to know, like how my children were developing or what their interests were," she says.

"In the end I'd take the photos out and not read the letters as it was too painful."

Hanna didn't write back, because her feeling of loss was too overwhelming. Then, four years after the adoption, when her life was getting back on track, she finally put pen to paper.

"I wrote and told them about my life: that I had a loving partner now, and that I was working. I told them about my job and where I lived, and how much I missed them, how hard losing them had been for me, and how I thought about them every single day and wished they were with me," Hanna says.

But some weeks later she received notification from her local authority that her letter had not been sent because some of its content was "inappropriate".

In the UK, the local authority's adoption agency acts as a middleman in the letterbox correspondence. This is partly so that names and addresses are not disclosed - but council officials also check what people write.

"Social Services told me I shouldn't say where I worked, that I shouldn't say, 'Wish you were with me.' Everything had to be positive. I phoned for help but they just kept sending me leaflets on how to write a letter that made no sense. So I gave up."

After a while, letters stopped arriving from the children too.

Helping birth mothers write these letters was Mike Hancock's job for 10 years. He works for the PAC Family First Service, which local authorities may contract to help them fulfil their statutory duty to support the birth parents of adopted children.

"We have to think about who's receiving the letter, whether the local authority will send it on, and whether the adopters will show the children," he says.

"You're not encouraged to be emotional in these letters. If the birth parent is very upset and misses the child they can't put it in, as it will upset the kids."

The first letter is the hardest, he says.

"Sometimes the parents are so cross, hurt and distressed that they don't want to write. Many of the mothers are like rabbits in the headlights. They're traumatised by their own experiences and the adoption. They've lost their kids and are grieving. Often they'll have problems with literacy."

Birth parents and adoptive families both have the right to ask for support with letter-writing, but the quality and provision is patchy, says Anna Gupta, professor of social work at Royal Holloway University. Some local authorities will have designated letterbox co-ordinators who support and facilitate contact, others will contract the service out, while others may have nothing at all.

Had Hanna had Mike Hancock's support all those years ago, things might have turned out differently. She may have succeeded in sending a letter to her children, and may have continued receiving them in reply.

Every year Hanna and her husband would celebrate her children's birthday and sing happy birthday, not knowing whether they would ever know any more about them.

"For years I worried about them and I'd have nightmares that they had been killed… I didn't know, would I be told?"

When Hanna found out her own death was imminent, her question was whether her children would be told.

She informed her local authority that she had stage four kidney failure, had been given six months to live, and wanted to get in touch with her twins. But nothing happened.

Two months later, Hanna received a bundle of 12 old letters from the adopters that the local authority had "lost" - and that was it, she says.

Then, over a year later, she was contacted by PAC for a different reason, and told them her story. The PAC worker set about co-ordinating with Social Services, who traced Hanna's children's adopters and informed them of her pressing health condition.

In the meantime, PAC helped Hanna construct the letter to her children to re-establish contact. It was finally sent to the local authority in 2020, long after doctors had expected she would die.

"I finally got to tell my children lots of things that I'd carried around in my head that I wanted them to know," she says. In this letter she told them she had thought about them every single day, had put their things from when they were babies in a box, and had pinned their photos up on all of her walls in her house. She had had to be sedated when they were taken from her because she couldn't cope, she wrote.

But when the letter was sent to Social Services, once again Hanna was informed that it would not be sent on - though they said it would be kept on file for her children to access, should they want to, once they turned 18, two years later.

A much shorter letter was sent in its place. This time, Hanna was allowed to express how much she loved her children and to say that she had health problems - but not that she was gravely ill.

"In the letter they didn't want me to say I was as poorly as I am. They said that the first letter had too much information and they didn't want to upset the children... They don't know that I have nearly died on four occasions."

Letterbox rules

The nature of letterbox contact differs from one local authority to another, according to research by the Nuffield Family Justice Observatory. Some only allow letters, others allow the exchange of photographs, small gifts, drawings, art or cards. In some cases correspondence is only allowed between adults, in others adopted children may be more directly involved.

In a 2018 study, external, Prof Anna Gupta also found that there was little agreement between local authorities on what constituted "appropriate content". Some adoption workers will read all letters sent in and go back to the letter writer if anything needs to change, while others may not. One adopted interviewee in Gupta's study said parts of the letters she had received throughout her childhood had been blacked out - but behind the black ink she could see her birth parent telling her how much she loved her.

Shortly after sending this letter, Hanna received a photograph of her children from the adopters.

"The day I received the picture of the children I was waiting to go for an operation. I was so scared that it would go wrong - I needed to know they had got my letter. It made me more determined to never give up."

Since then she has had a letter from each of her children, informing her of their studies and interests but making no reference to her illness, so she doubts that they have been told about it. In letterbox contact, it is always the adoptive parents who receive the letter and it is up to them what they tell the children.

For me, these children are potentially losing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity

Prof Anna Gupta, who practised as a social worker for 30 years, argues that Hanna's children should be told about her illness and given the chance to meet their birth mother before she dies - and she warns that the children may come to resent it if they are not.

"For me, these children are potentially losing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. If I was the social worker, I would be speaking to their adopters and asking them whether they wanted their children to come back years later potentially knowing that they'd deprived them of their last chance to meet their birth mother."

Gupta's research shows that many adopted children do want to know about their birth parents at some point in their lives.

"A big message from young people was that we need to prepare adopters that they will look - it's not about them and their abilities as parents, it's about the sense of who they are and where they belong," she says.

One man Gupta interviewed was adopted at the age of four. "He was a successful CEO and had a great adoptive family, but he would wake up every day and ask, 'Who am I?'" she says. "Even though he could remember police tearing him away from his mother's arms he still felt that she had abandoned him," she says. Meeting her could have reassured him that she had not, Gupta argues.

Research by another expert, external in the area, Prof Beth Neil of the University of East Anglia, shows that letterbox contact, if well-managed, can contribute to an adopted child's sense of self and identity, as well as familiarising the child with their birth family and reassuring them that they have not been rejected or forgotten about.

But her research also shows that letterbox contact often breaks down, as happened in Hanna's case.

Neil has found that most letterbox arrangements are inactive by middle childhood, with many failing to get off the ground in the first place. Many children were unaware that the correspondence was even happening.

So, increasingly, contact is being made between adopted children and birth parents on social media - bypassing formal processes and support. In 2018, an Adoption UK survey found that a quarter of adopted teenagers had had some form of unmediated contact with their birth family in the previous year.

This is raising questions about possible improvements to letterbox contact.

Some have argued that in an age where letter-writing has become less common, other forms of communication may be more appropriate. At least one local authority has now moved to face-to-face contact - either in person or, during the pandemic, by video-conferencing.

In a speech in 2018, external, when Lord Justice McFarlane took over as President of the Family Division, he suggested that adopted children should have contact with a broader range of birth relatives, particularly siblings, and questioned whether, once a child has settled down in a new family, the adoptive parents should continue to "have an effective veto" on contact between the child and the birth family.

For the Hannas of the future, this could be good news. But for Hanna today, still only 32, the best she can hope for is that she will continue to defy medical prognoses and that her health will hold out until her children decide it's time to look for her.

"I'm a fighter. I'm not going anywhere until I'm ready. My next step is to meet my children," she says.

"If I'm alive, they can find me. If not, when they look they'll see the court papers that show that I fought every step of the way to keep them."

Hanna is a pseudonym

Illustrations by Emma Lynch

You may also be interested in:

George is one of tens of thousands of children in the UK who've been taken into care because their parents are unable to look after them. Severely neglected, he struggled to express himself, so when there was something very important he wanted to ask his foster family, he chose an unusual way of doing it.

'Our foster child asked us to adopt him - by drawing himself on to a family photo'