Nil-by-mouth foodie: The chef who will never eat again

- Published

Loretta Harmes hasn't eaten for six years, but she hasn't lost her passion for cooking. Even though she cannot taste her recipes, she has a growing following on Instagram, where she's known as the nil-by-mouth foodie.

Loretta crunched into a roast potato and savoured its fluffy insides. She and her mum, Julie, had taken great care to get everything just right because they knew this would be her last ever meal.

In a matter of minutes, a familiar pain would squeeze her stomach like the wringing of a dishcloth, just as it always did whenever she ate or drank anything. Then she would feel painfully full and sick. As if her stomach had been pulled so tautly it would burst.

But she set that aside to enjoy the moment in her family's kitchen, the place where her cooking skills had flourished as a child.

"Sitting down to eat with my mum and sister felt surreal and amazing," she says. "We tried to act like a normal family for once."

It was 2015, and Loretta, 23, had already been surviving on liquidised meals for years. She almost never joined her family at the dinner table. Even picking up a knife and fork felt unusual, let alone chewing the potato and the chicken seasoned with lemon and garlic.

But today she had been asked to eat solid food by a bowel consultant, who wanted to understand why eating left Loretta in such agony - and why she might not be able to go to the toilet for weeks or even months.

Loretta had travelled to St Mark's Hospital in London earlier that day to have a thick orange tube threaded through her nose and down into her small intestine, to check the nerve function of her digestive system.

Finally, after years of being disbelieved and misdiagnosed, someone was investigating her problems properly.

When Loretta was a child, she and her nan, Mavis, would replicate meals from the cooking game show, Ready Steady Cook.

"She was the queen of baking, and the birthday cakes she made me were legendary," says Loretta.

"My sister Abbie and I would fight over who got to lick the cake bowl clean."

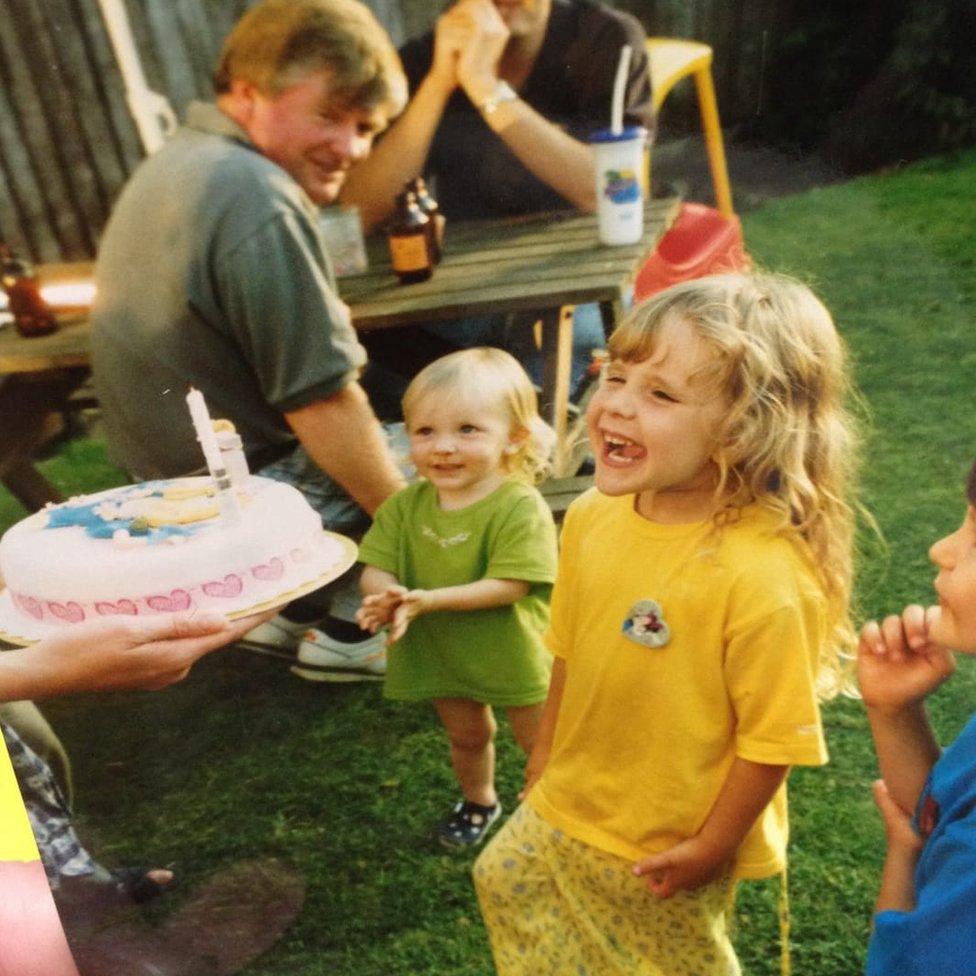

One of Mavis's birthday cakes for an excited Loretta

Lots of her stories about food glow with warm and joyful memories of family life.

Every Thursday her entire extended family would go to Mavis's house for a meal.

Loretta fondly remembers sitting around the big dining table and eating roast dinners and raspberry mousse.

"Everyone would make sure my grandad Eric didn't get hold of the gravy boat first, because there wouldn't be any left for the rest of the family," she says.

By 11 Loretta was cooking dinner for her family every Tuesday night when her mum worked late. She ran a hairdressing business from the garage and her clients became used to Loretta coming in every so often with a wooden spoon of sauce for her mum to try.

"I would have free rein in the kitchen and loved the idea of creating something from scratch for my family to enjoy," she says.

Loretta having breakfast in Mavis's garden

She started out by replicating her mum's tomato pasta bakes but soon graduated to pies and stews. Loretta's meatballs and a sticky chicken salad were family favourites.

At secondary school she won cooking competitions, holding her own against older students, and made it into regional heats. While other children stuck to pasta, Loretta was making beef bourguignon and marinated pork loin.

Her mum Julie says Loretta was - and still is - a very messy cook. The sort who seems to use every single pot, pan and utensil in the kitchen. But she didn't mind because she saw how much Loretta enjoyed it.

"Loretta's favourite thing was to make a meal out of whatever was in the kitchen cupboards - she was very creative," Julie says.

When she was 15 Loretta had anorexia, though she says it lasted for less than a year. Throughout her teens she also complained of digestive problems, which would flare up from time to time. But for most of this period she still managed to happily cook and eat, with Julie playing sous chef whenever Loretta couldn't manage alone.

Julie with Loretta (right) and Abbie

At the end of school Loretta was awarded a place at a top culinary arts college in London. She hoped to follow in the footsteps of alumni like Jamie Oliver and Ainsley Harriott. But she only managed to complete one year of the three-year course because of her health.

At 19 she went from just about managing, to becoming bed-bound by pain.

"Things went downhill dramatically - I couldn't eat or go to the toilet at all, and then the next five years became a nightmare I couldn't wake up from," she says.

This nightmare began with a doctor who was convinced that Loretta's rapid weight loss could only have been caused by the return of her anorexia.

Mental health services soon got involved and Loretta spent more than two years in eating disorder units. At one point she weighed just four stone.

Forcing herself to eat in order to gain weight seemed to her the only way out of the cycle, even though the pain it inflicted was severe.

Her desperation would sometimes turn to rage and she was sectioned under the Mental Health Act three times, for a total of 18 months to stop her leaving.

"I told them repeatedly that the only reason I am depressed is because of my bowel and stomach difficulties, but they didn't believe me," she says. Delusional psychosis was added to her medical notes.

She attempted suicide several times because of the hopelessness she felt at not having any treatment for her pain.

Life in the units was a bleak and unrelenting cycle of weighs-ins - the first at 6am - blood tests and food.

Patients would visit the kitchen for six meals a day - three main meals and three snacks.

She still remembers the chart hits which would loop back around incessantly on the radio.

Sia - Titanium: "I'm bulletproof, nothing to lose, fire away fire away."

Loretta today, at work on a recipe

All meals had to be finished within a set timeframe. The radio would be turned off when the time was up, and Loretta would be left staring at the food left on her plate. Tinned fruit and yoghurt or boiled vegetables with processed meat.

Nobody else was allowed to leave the table until she had finished, and she says staff and patients would heckle and bully her to hurry up.

After every meal patients spent an hour being watched closely in the communal living room to make sure they didn't try to get rid of the food they'd just eaten.

Most days Loretta would just curl up in a ball on a chair, trying to alleviate the pain she was in. Others read, did colouring or watched the television. One woman, who Loretta says had been in and out of these units for 13 years, would scream and scream but nobody was allowed to leave the room to escape it.

Loretta often felt like screaming herself, especially when she was under section and a member of staff would be sitting within touching distance of her throughout the entire night and day for weeks.

"I craved peace and quiet from it all," she says.

"I fully recovered from anorexia, it was a life lesson which became a life sentence."

Years later Loretta's reaction to the roast potatoes would help lead to a diagnosis of hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), a genetic illness that can manifest itself in lots of different ways.

What the test showed was that Loretta's stomach is partially paralysed and cannot empty itself properly. Confining her to a secure unit and forcing her to eat had been pointless.

Her other symptoms include migraines, fatigue, a racing heart when she stands up or sits down and a neck pain she will eventually need surgery for.

Until recently there has been relatively little research into hEDS and the 12 other types of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, and the condition is still not fully understood.

What is Ehlers-Danlos syndrome?

Ehlers-Danlos syndromes are a group of 13 disorders affecting connective tissue. This is tissue that supports, protects and gives structure to other tissues and organs in the body - it is found in skin, bone and ligaments, for example.

In Loretta's case, there is damage to the connective tissue in the wall of her intestines, and as a result food travels less smoothly through her digestive system. (Her stomach paralysis is a separate but linked condition.)

The syndromes are generally characterised by joints that stretch further than normal (joint hypermobility), skin that can be stretched further than normal (skin hyperextensibility), and tissue fragility.

One side-effect of having stretchy skin is its soft and youthful appearance. "My skin is like pizza dough and so soft - so there are some upsides!" says Loretta.

Source: Ehlers-Danlos Society, external

On average it takes 10 to 14 years for people to be diagnosed, says Dr Alan Hakim of the Ehlers-Danlos Society, because the symptoms of hEDS are so varied and may not appear to be linked.

"A person can find themselves seeing doctors and therapists for each of their individual concerns, without there being an overarching sight of all of them," he says.

"It is only when someone joins up the dots that the penny drops that this is a syndrome."

He says this is improving, as the syndrome becomes better known.

Six years on from her last meal, Loretta knows she will never eat or even drink a glass of water again. She is now fed by total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which means she is hooked up for 18 hours a day to a heavy liquid feedbag which bypasses the digestive system and infuses directly into the bloodstream. A tube known as a Hickman line goes through her chest and into a large vein that drains into her heart.

She is seen on her Instagram account, the.nil.by.mouth.foodie, external, swinging the feedbag into a rucksack she has customised in order to be able to go out and about. She's been known to ask people to hold it for her while she dances on nights out, a system which works well as long as they don't stray too far and pull on the line.

But the TPN is not without its drawbacks - even the smallest speck of dust can contaminate the line. Several times, she has had sepsis, a reaction to infection which can cause organ failure or even death.

"Still, despite its limitations, TPN has given back more than it has taken away," she says.

Before, Loretta felt so weak she spent most of her life in bed. Her body was so starved of nutrition that her bones became brittle and porous like a honeycomb, and her menstrual cycle had shut down completely. But worst of all was the constant pain.

"TPN restored my weight and gave me energy. It was nice to wear normal clothes again and not have to shop in the children's section," she says.

This improvement in her health has allowed her to revive her passion for cooking, though to conserve energy she sometimes cooks things in stages, and moves around the kitchen on a chair with wheels.

Being a chef who doesn't eat has given her a unique platform on Instagram.

Her flatmate Amy, a professional photographer, takes the photos and tastes the food. Starting in the early days of lockdown, they have begun building a business out of it - working with brands on recipe development and food styling.

"The reason I don't go stir-crazy over not being able to eat is because I'm so relieved to be free from the pain after so many years," Loretta says.

"The cooking itself is what I get pleasure from - being in the kitchen is a real creative outlet for me.

"If I am ever worried or anxious, as soon as I get cooking it fades because I am too busy concentrating on the dish I am making."

Loretta and Amy: Loretta sniffs the food, while Amy tastes it

Amy is happy to be the one to eat Loretta's creations.

Mac and cheese lasagne. Avocado key lime pie with a coconut pecan crust. Cauliflower rarebit. "She makes things up out of her head that I've never seen before," says Amy.

To make up for not being able to taste the food, Loretta spends a lot of time methodically planning and preparing. She draws on the years she spent poring over recipe books and experimenting in the kitchen - and her intuition.

"I cook with my eyes, nose and gut instinct," she says.

Inhaling the smell of a bubbling sauce will trigger her memory of the taste and her eyes can judge the depth and richness of it.

Some people who rely on TPN like Loretta will chew food and spit it out, but that's never appealed to her.

"I don't actually crave the taste of food itself, it's the comfort of it that I miss and the memories of what food means," she says.

"Ice creams on the beach, a hot chocolate on a cold day, having a roast with my family at Christmas." Cucumber remains her favourite smell because it reminds her of childhood picnics.

"So much of what we do socially is around food - I do still feel like the odd one out sometimes. I will still go to people's birthday dinners or 'out for a coffee or drink' - I just can't participate in the actual eating and drinking."

The avocado key lime pie

Almost all of her happy memories of food feature her sister, Abbie.

Abbie was so struck by her big sister's traumatising experience in eating disorder units that she chose to work in a mental health hospital for children.

During Loretta's last meal, Abbie was there capturing the moment on her smartphone and helping to make it feel special.

In 2019, together with their mum, Julie, Abbie visited Loretta in hospital, where she was recovering from another bout of sepsis. But tragically Abbie was killed in a car crash on the way home. She was only 23.

"She made so much difference to the lives of others and her own life was just beginning to blossom," says Loretta.

Loretta feels that she must live for both of them now and this spurs her on to make the most of her life.

The last time I speak to Loretta she is in hospital recovering from her ninth bout of sepsis since beginning TPN.

Lying in the intestinal failure unit she dreams up the recipes she will make when she has recovered and returned to her flat in Bournemouth.

"The first thing I'm cooking when I get back in the kitchen is a hearty healthy breakfast," she tells me from her bed.

How that hearty breakfast turned out

She got a waffle maker at Christmas and can't wait to use it.

"I am going to make sweet potato waffles topped with sauteed spinach and mushrooms, smashed avocado, roasted cherry tomatoes with a balsamic glaze."

If you need support with an eating disorder, visit the BBC Action Line website for details of organisations that can help.

You may also be interested in:

The Hadza are one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer tribes in the world. It's thought they've lived on the same land in northern Tanzania, eating berries, tubers and 30 different mammals for 40,000 years. Dan Saladino went to watch them foraging and hunting, and to ask whether their diet holds lessons for everyone.