Bobby Sands: The hunger strike that changed the course of N Ireland's conflict

- Published

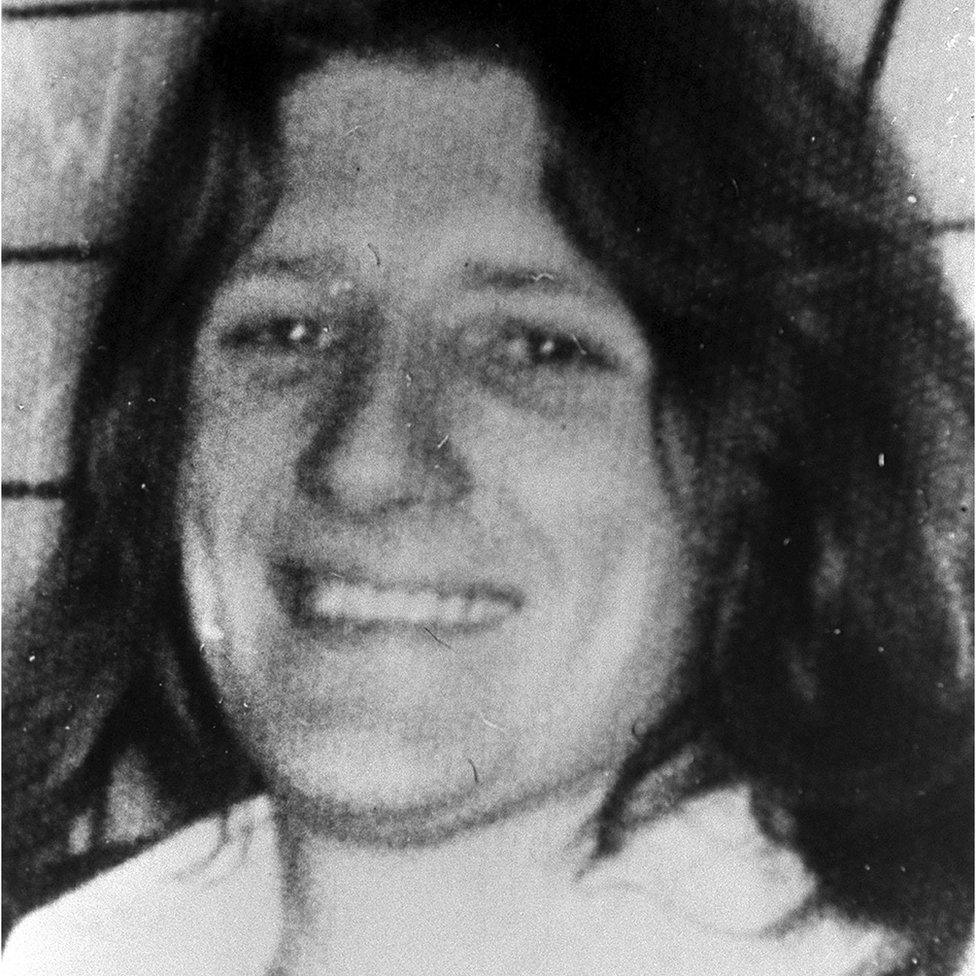

Forty years ago, on 5 May 1981, 27-year-old Bobby Sands, the IRA's leader in the Maze prison outside Belfast, starved himself to death. Peter Taylor, who covered the story at the time, says it marked a watershed in Northern Ireland's Troubles, helping to pave the way for the IRA's political wing, Sinn Fein, to become today the largest on the island of Ireland.

The seeds of the hunger strike had been sown in 1976, when the Labour government of Harold Wilson abolished the "special category" status that IRA prisoners had previously been granted, allowing them, among other things, to wear their own clothes.

The question of clothing was important to them because they claimed they were "political" prisoners, fighting to achieve the IRA's historic goal of a united Ireland; prison uniforms criminalised them, they argued.

So many responded to the Wilson government's withdrawal of the right to wear their own clothes, by wearing nothing.

Gerard Hodgins, a Belfast Republican sentenced to 14 years for terrorist offences and IRA membership told me what happened when he arrived at the specially built H-blocks, at the Maze.

"I didn't identify myself as being a criminal. The prison officer was there saying, 'Right, you're here to do your time. You can do it the hard way or the easy way. If you take my advice, you'd get them uniforms on you now. If not, strip.' So you stripped there and then whilst you were being ridiculed and jeered at by the screws."

The so-called "blanket men", who covered themselves in the blankets left on their beds, made five demands: the right to wear their own clothes, not do prison work, to organise their own studies, receive parcels from home, and enjoy freedom to mix with their comrades. They were savvy enough to realise that the government would never grant political status in name.

But their protest excited little sympathy outside the walls of the prison. The Nationalist community remained largely uninterested and apathetic. The government stood its ground, sensing it was on the winning side.

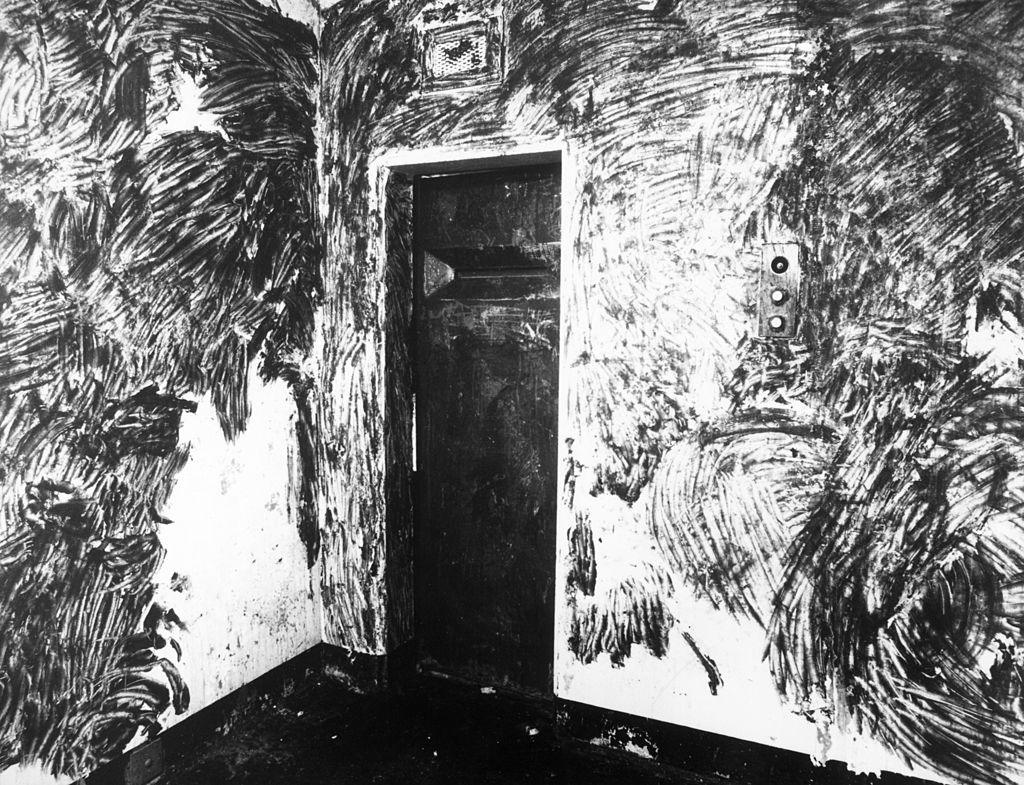

So the prisoners then escalated the protest, refusing to "slop out" the chamber pots left in their cells, as there were no toilets. Instead they slopped their urine on the floor and daubed the solid waste on the walls. It became known as the "dirty" or "no-wash" protest.

"You become accustomed to it. You were waking up in the morning with maggots in the bed with you," said Gerard Hodgins, who lived like this for about three years. "It just gets to the stage where you brush them off again."

Cathal Crumley from Londonderry, who was sentenced to four years for IRA membership at the age of 18, told me he used to sweep the urine under the prison door.

"I remember for years sleeping on a piece of sponge that had been soaked by urine that was pushed back under the doors. It was uncomfortable, it was stomach-churning, but that was the battleground that had been created for us and we either survived or gave up."

By 1980, despite the horrific conditions, the "dirty protest" had still failed to galvanise much of the Nationalist community. Many simply believed the conditions were self-inflicted. With morale sinking, the prisoners decided to go for the nuclear option - the hunger strike.

They calculated that being ready to sacrifice their lives for their convictions would finally fire up their supporters and force the new Conservative prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, to compromise.

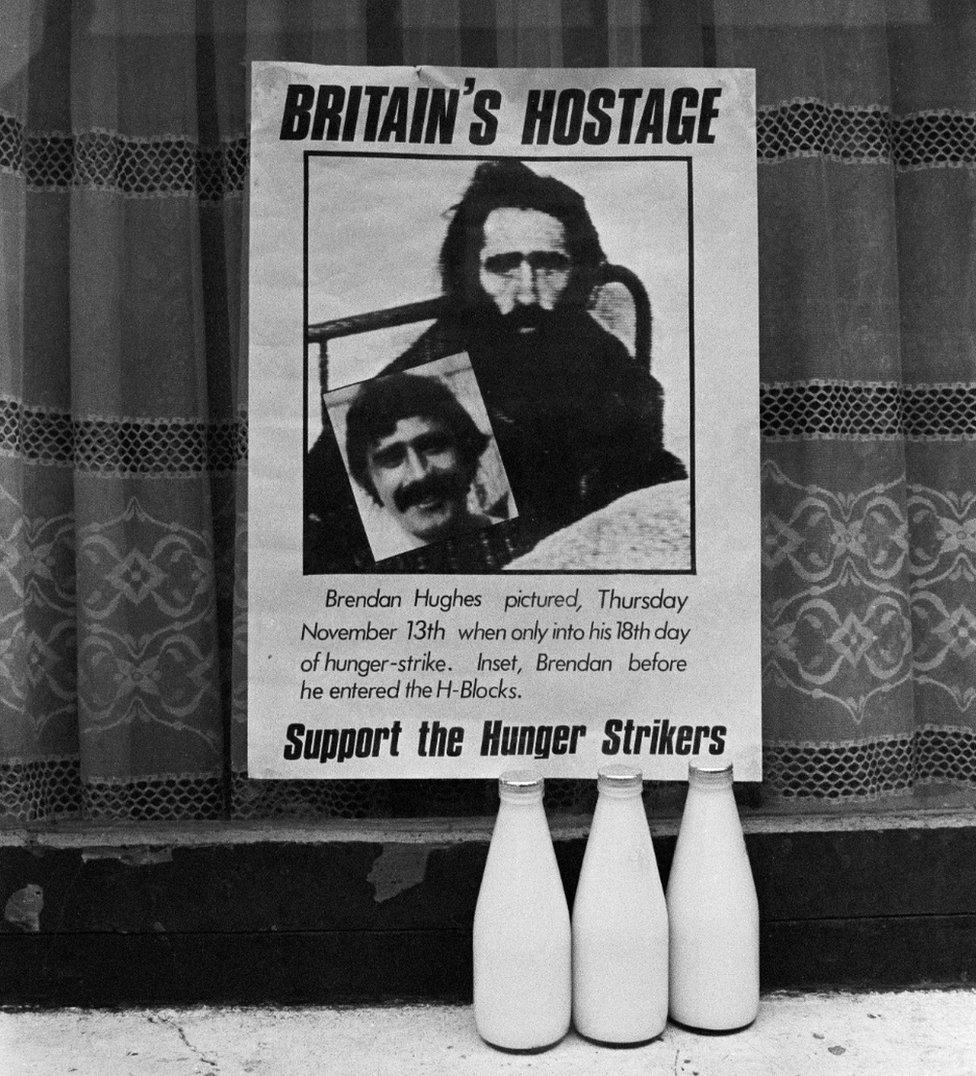

Seven prisoners refused food on 28 October 1980, and I remember having my doubts that they would go through with it. But they did. After 53 days they were staring death in the face when a compromise was agreed through a top-secret back-channel, facilitated by MI6 officer Michael Oatley.

A poster shows 1980 hunger striker Brendan Hughes gaunt-faced and wrapped in a blanket

Remarkably the compromise was sanctioned by Mrs Thatcher. I asked Oatley - codenamed The Mountain Climber by the IRA - if the formula allowed prisoners to wear their own clothes.

"I think it left that sort of question rather open," he replied. "It did suggest some concessions."

The prisoners certainly ended their hunger strike in the belief that they were getting their own clothes - families brought them into the prison in readiness - but the government had other plans.

I well remember a Northern Ireland Office official in Belfast opening his desk drawer and producing a shirt still crisp in its Marks and Spencer's wrapper. "Look," he said proudly, "we're going to give them, not their own clothes, but brand new clothes."

"But they'll never wear it," I said. And they didn't.

Listen to The Hunger Strikes on Archive on 4, on Radio 4 at 20:00 on Saturday 1 May

The compromise collapsed. The prisoners accused the perfidious "Brits" of betrayal. I asked Michael Oatley what had gone wrong.

"I think that at the end of the first hunger strike the prison regime was not altered sufficiently to meet the expectations of the prisoners," he said.

I think that was probably putting it mildly. Today Oatley describes the hunger strike as "a searing tragedy that could have been avoided".

Two months later, when I heard that the IRA's commanding officer in the Maze, Bobby Sands, was to lead a second hunger strike, starting on 1 March 1981 - the fifth anniversary of the abolition of special category status - I knew that this time, failing any compromise, it would be to the death. Nine volunteers followed Sands.

Demonstrators in Belfast hold a silent vigil for the 1981 hunger strikers

Mrs Thatcher never wavered.

"Crime is crime is crime," she declared. "It is not political. It is crime. There can be no question of political status."

Nor was there any compromise on the IRA side. It was destined to be an epic struggle between the Iron Lady and the iron-willed men.

Then came a totally unexpected event. A snap by-election was announced for the Westminster constituency of Fermanagh/South Tyrone, and Sinn Fein's Jim Gibney, sensing that outside support for Sands and the other hunger strikers was ebbing, suggested to Gerry Adams - then the party's vice-president - that Sands should stand as a candidate.

After much discussion, Adams assented and Sands agreed to run as an Anti-H-Block/Armagh Political Prisoner candidate. (Armagh was the women's prison.) Confounding the government's expectations, Sands narrowly won the election by 1,446 votes on a turnout of 87%.

The Unionist MP, Ken Maginnis, probably reflected the view of the vast majority of his Loyalist constituents when he said he was surprised and horrified.

"I couldn't believe that my Roman Catholic neighbour, whom I'd always treated with a great deal of respect, could then go out and vote for someone who was going to murder me or murder some of my friends and who was an enemy of this particular community. I just couldn't believe it."

It proved to be a critical turning point though, changing the course of the conflict.

"It was very, very difficult before Bobby Sands was elected, to argue internally that the way forward was through standing Sinn Fein in elections," Jim Gibney told me. "It was one of the high points in terms of convincing Republicans of the merits of electoral politics."

A month after his election, and after 66 days on hunger strike, Bobby Sands MP died.

Around 100,000 mourners came to his funeral, again confounding the expectations of the government, which believed the hunger strike had limited support. To those who marched behind his coffin, Sands was a martyr, Margaret Thatcher a murderer.

Some of the thousands who turned out for Bobby Sands' funeral on 7 May 1981

"Mr Sands was a convicted criminal," the prime minister said. "He chose to take his own life. It was a choice that his organisation did not allow to many of their victims."

Over the next three months, nine other hunger strikers were buried with full IRA honours. Most had gone without food for over 60 days.

Mrs Thatcher scented victory.

"Faced with the failure of their discredited cause, the men of violence have chosen in recent months to play what may well be their last card," she said.

But prisoners were still joining the hunger strike into the autumn. Gerard Hodgins refused food on 14 September. He knew exactly what he was doing.

"The hunger strike came to encapsulate the whole struggle for us. We believed if we lose out on this one, we've lost this war. Everything that we've sacrificed up to date would have been in vain."

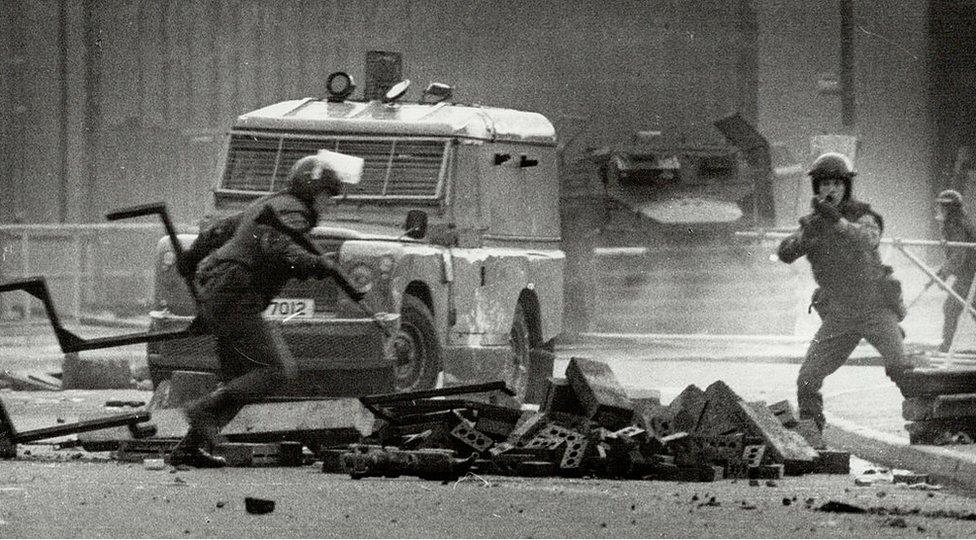

A British soldier tries to clear a barricade during riots following Bobby Sands's death

He ended his strike on 3 October, along with the rest of his comrades, after it became clear that their families would authorise medical intervention to save the lives of their sons.

By now, Mrs Thatcher had sent James Prior to Belfast as Northern Ireland secretary, to try to resolve the hunger strike. Prior, an arch conciliator, intimated concessions - and, once the strike was over, modified prison rules.

Prisoners were allowed their own clothes, permitted to associate freely, granted more visits and excused prison work. On the face of it, the hunger strikers had won - but at a terrible cost.

James Prior, arch conciliator

A month after the end of the hunger strike, at Sinn Fein's annual conference, the party's director of publicity, Danny Morrison, first gave voice to the slogan, "The Armalite and Ballot Box" - the phrase reflecting the fusion of violence and politics that was to define IRA/Sinn Fein strategy for next 15 years.

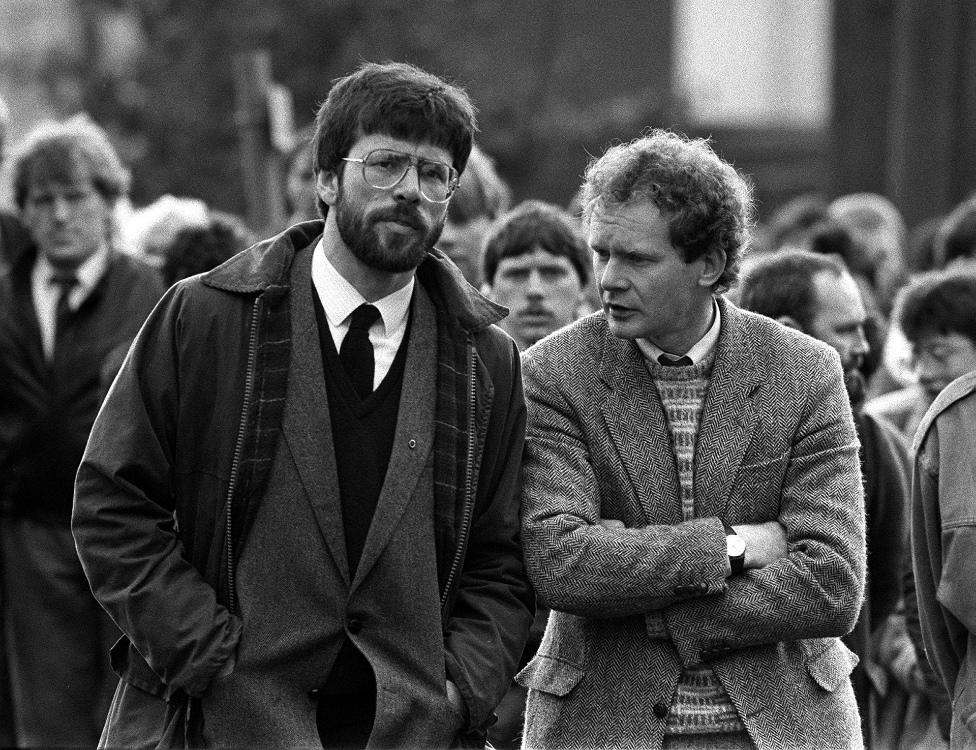

The next year, Martin McGuinness, who had told an Irish court in 1973 he was proud to be a member of the Provisional IRA, was elected to the Northern Ireland Assembly, and in 1983 Gerry Adams was elected to Westminster. That was the Ballot Box. The Armalite followed in 1984 when the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel, Brighton, where the Conservative Party was holding its annual conference. Five members of the party were killed. Mrs Thatcher narrowly survived. To the IRA leadership and rank and file, it was seen as revenge for the hunger strike.

Also by Peter Taylor:

The party's momentous political advance was finally crowned when Martin McGuinness, once arguably the most powerful IRA leader on the island of Ireland, became deputy first minister in the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly, sharing power with his once bitter enemy, Ian Paisley. Astonishingly, McGuinness then went on to dine in white tie and tails with the Queen at Windsor Castle. He did so, he told me, "to reach out the hand of friendship to the Unionist people of the North".

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness at an IRA funeral in 1987

The hunger strikes were pivotal in Sinn Fein's remarkable journey, which leaves it now the largest political party on the island of Ireland, sharing power in Belfast and knocking on the door in Dublin.

It is a transformation I never dreamed I would see when I was covering the hunger strikes from their origin to their dramatic climax.

How did the Northern Ireland secretary, who finally brought the hunger strike to an end, view Sinn Fein's advance? I interviewed James - by then Lord - Prior two years before he died aged 89. I asked him if he thought the Armalite and Ballot Box strategy had worked. He was remarkably candid.

"I expect with the benefit of hindsight, one has to say yes it did. However unpleasant that sounds, I'm afraid it did work."

I put it to him that governments can never acknowledge that violence works, while they are in power.

"No," he said. "It takes many years afterwards, such as you're asking me now."

Conflict in Northern Ireland: Some key events

1921

The island of Ireland is partitioned, and Northern Ireland established. Catholic minority in the North suffers discrimination in voting, housing and employment at hands of Protestant majority. Catholics are mostly Nationalist - favouring a united Ireland, governed from Dublin - while Protestants are mostly Unionist, preferring to remain within the UK.

1968

Mainly Catholic Civil Rights movement takes to the streets to demand an end to discrimination. Forces of the state resist.

1969

British troops intervene in Northern Ireland to stop sectarian rioting between Catholic and Protestant mobs. Provisional IRA formed with aim of using "armed struggle" to re-unify Ireland.

1971

IRA suspects are interned without trial in the disused RAF camp at Long Kesh outside Belfast. Internees detained in RAF Nissen huts in wired compounds that look like a WW2 German Prisoner of War camp. Behind the wire, detainees live like POWs, allowed to wear their own clothes, mix freely with their comrades and run their own regime. Arms training practised with wooden guns. Lectures on guerrilla warfare by inmates. Detainees regard themselves as political prisoners because their political aim is to re-unify Ireland - by armed force.

1972

The most violent year of the so-called "Troubles". Nearly 500 killed including over 250 civilians and 150 members of the security forces. The year opens with "Bloody Sunday" on 30 January when Paratroopers shoot dead 13 innocent Catholic civil rights marchers.

The Unionist-dominated Parliament at Stormont is abolished and direct rule imposed from Westminster, headed by a Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

Prisoners in Belfast's Crumlin Road jail go on hunger strike demanding "political" status, with the same privileges enjoyed by their comrades detained in Long Kesh. A hunger strike led by IRA Belfast commander Billy McKee lasts for 35 days. By then 40 other prisoners have joined him. Fearing violence on the streets should McKee die, Northern Ireland Secretary William Whitelaw makes concessions including the right for prisoners to wear their own clothes. The government calls it "special category status", refusing to call it "political status".

Secret peace talks take place between the British Government and the IRA leadership including the young Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness. The talks fail.

1976

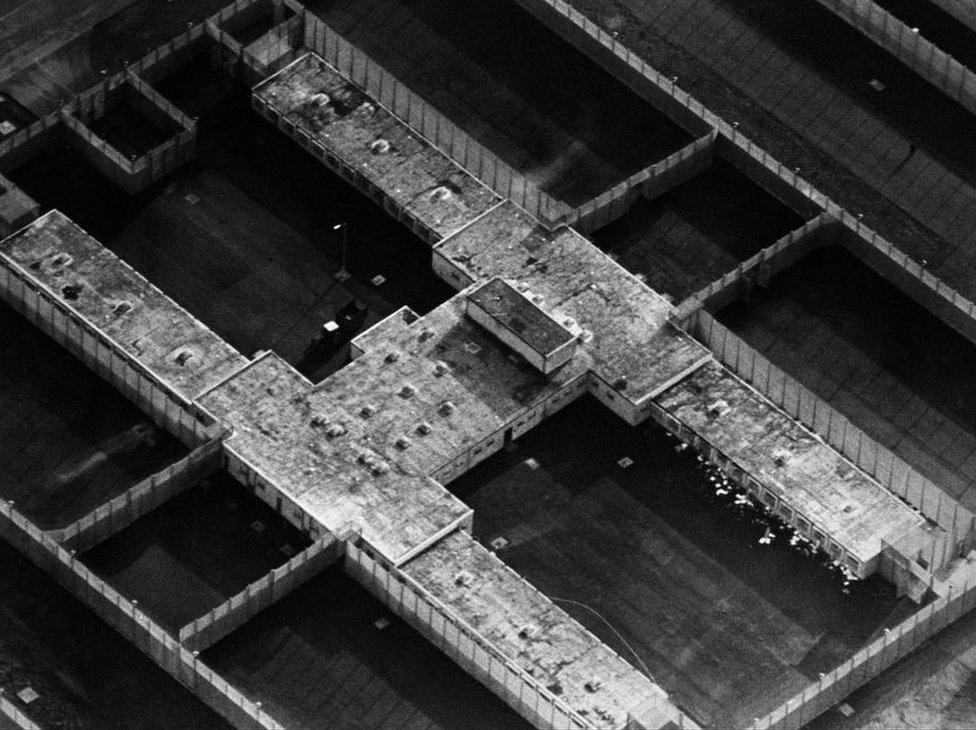

The government of Prime Minister Harold Wilson abolishes special category status and introduces a policy of "criminalisation" - using due process of law to arrest terrorist suspects and try them before special non-jury courts, presided over by a single judge. They're then to be sentenced to the new, specially built, high security H Blocks - so-named because of their shape. Long Kesh is renamed the Maze prison.

IRA prisoners refuse to put on prison uniform and wear prison blankets instead. They make five demands, including the right to wear their own clothes and privileges regarding work, education, visits, and free association outside cells. The government shows no sign of giving in.

Prisoners then escalate the protest, refusing to slop out the chamber pots in their cells - they daub excreta on the walls and pour urine under the cell doors. They live like this for three years.

1979

Margaret Thatcher becomes prime minister.

The IRA assassinates Lord Louis Mountbatten at his holiday home in the Irish Republic and on the same day kills 18 soldiers in an ambush at Warrenpoint.

1980

The prisoners press the nuclear button. The first hunger strike begins when seven prisoners refuse food. They call off the strike after 53 days just as one of their number is on the brink of dying. They are led to believe they are about to get their own clothes - the crunch issue in the confrontation. Families deliver them to the prison but they are never given to the prisoners.

1981

March: Bobby Sands, the leader of the IRA in the prison, goes on hunger strike, making clear he intends starve himself to death. Nine other Republican prisoners join him. Mrs Thatcher makes it clear there will be no compromise.

April: Sands is elected to Westminster, having stood as an H Block candidate in the Fermanagh South Tyrone by-election. I

May: Sands dies after 66 days on hunger strike. Around 100,000 mourners attend his funeral.

June: Two H Block prisoners are elected to the Irish Parliament in Dublin - one of them a hunger striker.

August: A 10th hunger striker dies. Sinn Fein's Owen Carron holds Bobby Sands' Westminster seat in the Fermanagh/South Tyrone by-election.

October: Families begin directing medical attention to save the lives of their sons still on hunger strike. James Prior becomes Northern Ireland Secretary. The strike ends and compromises are agreed. Prisoners get their own clothes and gradually the restoration of other privileges.

1982

Martin McGuinness, the former IRA leader and now Sinn Fein politician, is elected to the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly.

1983

Gerry Adams, Vice-President of Sinn Fein, is elected to Westminster. He becomes president of Sinn Fein later in the year.

1994

IRA ceasefire, followed six weeks later by Loyalist paramilitary ceasefires.

1998

Good Friday Agreement signed by all parties to the conflict.

2020

Brexit - the UK leaves the European Union. Sinn Fein becomes the largest political party on the island of Ireland.

2021

To avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland, a notional customs border is placed in the Irish Sea, setting a trade border between Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Peter Taylor has been reporting on Northern Ireland since 1972