Who Won The War? Revisiting NI on 20th anniversary of ceasefires

- Published

Peter Taylor returned to Belfast to revisit some of the key people he had spoken to during his 42 years of reporting the conflict in Northern Ireland, to ask if their opinions had changed

I was initially approached by BBC Northern Ireland well over a year ago to ask if I would I be interested in making a documentary to mark the 20th anniversary of the IRA and loyalist ceasefires of 1994. We knew this film had to be about more than just the ceasefire. It should cover much wider issues raised by the conflict, the peace process and the eventual settlement.

The most effective way, we believed, was to revisit many of the key people from all sides who I had interviewed over my 42 years of reporting the conflict, show them extracts of what they had said at the time and ask them do they still feel the same. Our aim was to discover if their views had changed in light of today's Northern Ireland.

At this planning stage I had brought along a photograph of a 12-year-old boy from Divis Flats in west Belfast who I had interviewed way back in 1974. Memorably, he had the initials IRA tattooed on the back of his hand. His name was Sean McKinley. He said he wanted to fight and die for his country.

During an interview in 1974, 12-year-old Sean McKinley told Peter Taylor he wanted to fight and die for Ireland

The image of Sean had haunted me throughout my career and I often wondered what had happened to him. We made it a priority to track him down and talk to him again. At the time I did not even know if he was still alive.

'Startling'

I spent four months in Belfast making the film and revisiting some of the key watersheds in the conflict including Bloody Sunday (my initiation into the so-called "war"), the hunger strike and the election of Bobby Sands to Westminster which gave Sinn Féin its political impetus from the 1980s through to the present day.

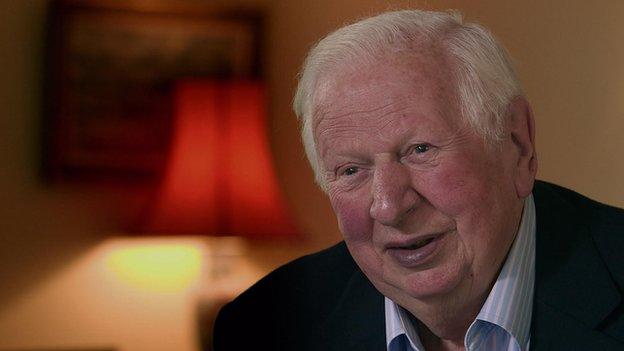

Some of the interviews I did were remarkable for their candour. Jim Prior, now Lord Prior, was Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher's Northern Ireland secretary who was dispatched to Belfast in 1981 to end the hunger strike. His interview was one of the most startling and unexpected. I asked him if he thought violence had worked. "I think violence probably does work," he said. "It may not work quickly and it may not be seen to be working quickly, but in the long run one has to look back and say, 'Yes, it did work.'"

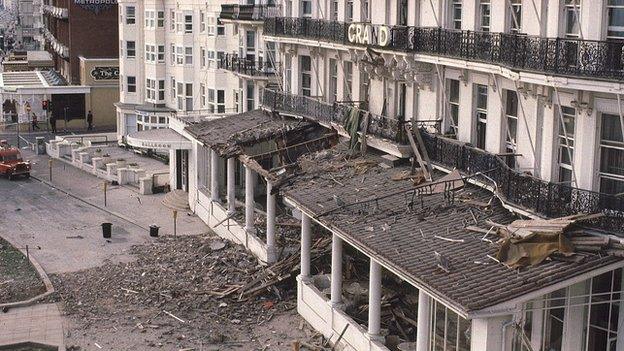

Five people died and 34 others were injured when the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton in October 1984 as it hosted that year's Conservative party conference

Norman Tebbit, now Lord Tebbit, made an equally surprising comment about the IRA ceasefire. As a member of Mrs Thatcher's cabinet he was severely injured in the IRA bomb attack on the Grand Hotel Brighton during the Conservative Party conference in 1984. His wife, Margaret, was paralysed for life. Through gritted teeth he said: "I have no sympathy for those who declared the war. But one way or another, a ceasefire was achieved and to that extent, it was a price that was worth paying."

Transformation

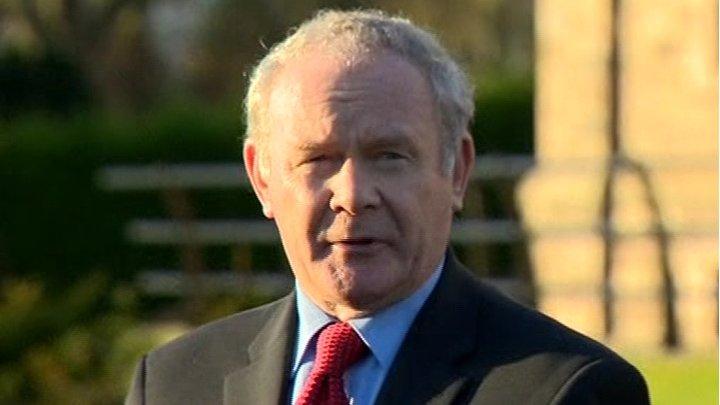

Sinn Féin's Martin McGuinness, who made the astonishing journey from IRA commander to deputy first minister, stood in Derry's Bogside and, undeterred by a wasp that was about to settle on his eyelid, talked about joining the IRA in 1970 and being taken to task by his mother who had found his IRA beret in the house. "It traumatised her," he said.

An equally remarkable journey was also made by the late Dr Ian Paisley - his transformation from "Dr No" to "Dr Yes" was explained by former Prime Minister Tony Blair in a revelatory interview. He described meeting Mr Paisley shortly after he had come out of hospital following a serious illness. He recounted what Mr Paisley had told him. "He'd been through a near death experience, he'd survived and it should be for a purpose. And if the purpose was peace and that was God's will as it were, then he should do that."

And what about Sean McKinley, the little boy with the initials IRA tattooed on the back of his hand? We finally found him after wearing out much shoe leather on the streets of west Belfast. I got a shock when the once fresh-faced little boy of 12 opened the door to my knock. He was now 52 and looked many years older. His hand still bore the initials IRA.

Sean had indeed "fought for his country" and as a result had spent many years in the Maze prison for the murder of a British soldier. I asked him what he would say to any little boy who said today what he had said 40 years ago about fighting and dying for Ireland. "I would advise him to forget it, because I know a lot of people who died, and they thought they were fighting and dying for their country, but it never worked out that way. It never worked out."

Meeting Sean again was a sad and salutary experience.

The documentary Who Won The War will be broadcast on BBC One NI on Monday 29 September at 21:00 BST.

- Published26 September 2014

- Published26 September 2014

- Published26 September 2014