Could my mum’s toaster help me care for her?

- Published

An emerging technology allows relatives to keep an eye on elderly or vulnerable people living alone by monitoring their electricity usage - but as with all innovations, there is the potential for misuse.

It's the second week of March and I am on Zoom having an argument with my mum about her toaster. I have just informed her that she has used the appliance twice so far that morning - once at 08:03 and again at 09:55 - but she's not having any of it.

"I had the toaster on earlier than that because I was up at 06:00," she declares. (My mother is not the sort to let an early start go unrecorded.)

"It's showing the kettle at five to six and 08:00," I reply with calm authority. "But the toaster not till 08:00."

"Well, I did use it actually." My dad, who is next to my mum on my computer screen, remains quiet. He knows better than to get involved.

The cause of the controversy - and the reason for my intimate knowledge of my parents' kitchen appliances - can be traced to a morning three weeks earlier, when an electrician installed a little white box in their meter cupboard. Thanks to this gadget I can now see when my parents are using their toaster, their oven, their microwave and a range of other appliances - all by just glancing at my phone.

Now, I don't care how much they use their toaster - honestly, I don't - but their appliance usage tells me that they are up and about. It could also alert me to worrying incidents such as the oven being left on or appliances being used at night-time.

As many countries contend with the challenge of an ageing population, devices like this might help elderly people live safely in their own homes. In the UK, 2.3 million people over the age of 75 live alone, according to the Office for National Statistics - a figure that has been steadily growing over the past 25 years.

Find out more

Listen to Watching out for Gran with help from her toaster from People Fixing the World on the BBC World Service

My parents are not especially vulnerable - they live together and are still completely independent. But my mum is, in her words, "a Parkie Person" - she has Parkinson's Disease, which is a degenerative condition - and my dad lives with a chronic form of cancer. I don't worry about them yet, but when I heard about this service, which is not yet available in Europe, I was keen to try it out, and so were they.

It is called Infocare, and it is offered by a company called Informetis. It uses a technology called non-intrusive load monitoring, or NILM.

Every second, the sensor in my parents' meter cupboard measures the electrical signal coming from their house, sampling it and sending the information to the cloud. Algorithms then examine the "noise" on the signal to work out which home appliances are in use. (At the moment, it is not possible to do this with smart meters alone, since those devices just measure electricity every 30 minutes.)

This produces an overview of appliance usage which could be used to cut down on energy bills - and some NILM companies are focused on this area. But the Infocare system builds up a picture of my parents' daily habits, and then sends alerts when things don't look quite right.

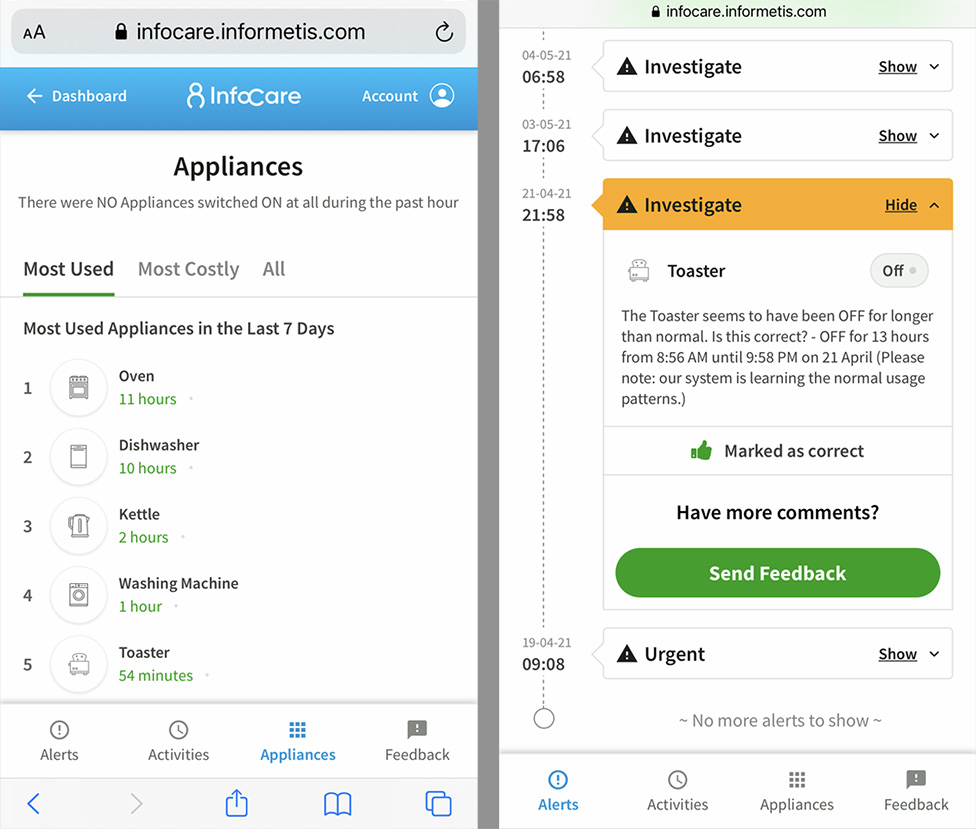

Infocare gives carers appliance and activity overviews, alerts, and a facility to correct faulty readings. The design will change if and when the product comes to market.

So for example, a few weeks ago I received an alert that my parents' toaster - yes, the toaster again - had not been in use all afternoon. That might seem a little random, but my dad normally has toast with his soup at lunchtime. If he was older, or living on his own, that notification might prompt me to call him to check he had remembered to eat that day.

But most mornings and evenings, I received a message that was blandly reassuring: "Everything appears to be 'normal' in your relative's home during the past 12 hours." (The phrasing of this message greatly amused the family, and everyone else that knows the family.)

There are obviously limits to what the technology can tell you, and what it should be used for. It can tell you if someone has boiled the kettle, but not if they have made a cup of tea and drunk it.

"Our technology is all about peace of mind," says Jay Chinnadorai, from Informetis. "It's not a medical technology. So if somebody needs their diabetes medicine to be taken every two hours, you don't use this to monitor that."

For several years, it has been up and running in Japan, where it is offered as an add-on service by the energy giant Tepco. The BBC visited one apartment building in Ushiku, a city about an hour north-east of Tokyo, where more than half the residents live alone. The building manager, Tomomi Kawai, can survey the residents' appliance usage from his office by the front door.

WATCH: The NILM technology up and running in an apartment block in Ushiku

"I remember one time we spotted an apartment where almost none of the appliances were being used," he says. "I went to that person's room and the resident was very frail and just needed someone to talk to." Mr Kawai helped the person to a local clinic.

When it gets hot in the summer, Mr Kawai will receive alerts if residents are not using their air conditioners, prompting him to check if they know how to use the machines. He believes most residents appreciate this attention, though one or two have reacted angrily when he has asked whether they have been struggling to sleep, after he spotted some nocturnal activity.

Tepco say that users' data is held securely and not shared, but there is potential for NILM to be used in all sorts of unsavoury ways. Not only does appliance data tell you when someone is away from home, but - if you know what to look for - it can reveal personal information, such as whether someone has a health condition.

"As it gets more popular I think you will see some quite unscrupulous uses of this technology," says Paul Fergus, a professor in machine learning at Liverpool John Moores University. "You can even foresee housing associations where you will be forced to gift that data as part of the tenancy agreement."

After developing their own NILM algorithms, Paul and his research partner Carl Chalmers were approached by a housing association who wanted to know who was playing music in the middle of the night. They have also been approached by insurance companies who want to profile their claimants, and an energy company who asked them to predict who might default on their bills.

As it gets more popular I think you will see some quite unscrupulous uses of this technology

The pair turned down these approaches and have instead focused on developing NILM as a diagnostic tool, publishing the first clinical trial of the technology last year. They believe it might help doctors chart the development of a disease like Alzheimer's, by measuring, for example, the onset of sundowning syndrome. This is when patients with dementia become more active in the evening and night-time.

"What you are trying to find is the pattern of that change and the rate of that change," says Paul, "and you're going to say, 'Look I think another three months' time we're going to be about here, and I think that package of care needs to provide these additional services.'"

When it comes to using NILM as a tool for monitoring the elderly, advocates say it offers carers meaningful data, but does not intrude on their relatives' privacy in the way that a camera surveillance system might.

NILM also avoids the pitfalls of the emergency alarms, which, for decades, carers have implored elderly relatives to wear around their necks. Elderly people often forget to wear the alarms, or simply choose to leave them in a drawer.

"They would do anything not to wear their pendant alarm," says Madeleine Starr, director of business development and innovation for Carers UK, who has taken part in a study about the attitudes of elderly people to technology. "They are incredibly stigmatising."

Pendant alarms can be life-savers, but they are not beloved by all users

She believes NILM has the potential to give reassurance to relatives without asking very much of elderly people.

"In traditional times we had the smoking chimney," she explains. "You lived over the road from your parents and in the morning they lit the fire and you saw the smoke and you knew they were OK. So this is like the modern equivalent."

It must be said, during our mini-trial it did not work flawlessly. The technology is still in a trial phase, Informetis tells me, and is working from a limited database of appliances. Various devices seemed to get mistaken for the kettle, and while I had no information about the hob, I heard a lot about a certain bread-oriented gadget.

"I just wonder if you actually use the toaster a bit more than you realise," I venture, on the call to my parents.

"Well, we lead separate lifestyles in this house, as you can see," my mum concedes. "I'm the 06:00 shift, he's the 08:00 shift." She nods her head towards my dad.

Bad toast probably is grounds for a row in my parents' house, but that isn't what was happening on that call. In fact, one of the key selling points of NILM is that it might keep conversations between carers and their relatives natural. As they get older, if I know that Mum and Dad have had their toast, it might avoid the need for an interrogation - "Have you had your breakfast?", "Have you been out today?" and so on.

And importantly, neither of them minded me observing their electricity usage, and they don't believe it changed their routines.

"We joked around a bit - 'Come on, let's put the toaster on…'" admits my dad. "But we haven't changed our lifestyle, and that's quite important I think - that we don't feel monitored."

Listen to Watching out for Gran with help from her toaster from People Fixing the World on the BBC World Service