'Talk to me': A train driver asking men to open up

- Published

As Scotland's only woman freight train driver, Heather Waugh was already a pioneer. Then a tragedy from her past inspired her to take on a new mission - getting men to talk about their mental health.

When it was time to set off, Heather briskly pulled a handle towards her: "Star Trek-style", she said, deadpan, as though she were Mr Sulu putting the USS Enterprise into warp speed. But this wasn't a spaceship; it was a British Rail-vintage Class 90 locomotive. Its motors growled, then the train shuddered forward.

Behind her, container wagons stretched down the line for three-quarters of a mile. It wasn't Heather's job to know what sort of cargo she was carrying, just how much it all weighed - tonight, a little under 1,500 tonnes - and whether it included anything hazardous. Her task was to drive the lot of it south through the valleys of lowland Scotland and beyond.

In the cab, with her right hand on the power controller and her left on a train brake handle she was deep in concentration and looked, in spite of the clatter and din around her, entirely serene.

Heather, 44, drove passenger trains for 15 years before switching to Freightliner, her present employer, in 2019. And after so much practice in the rain and darkness, she could anticipate every gradient and curve of the line ahead. She knew how fast to approach each corner; when to apply the brakes and how long it would take before the wagons at the back would actually start to slow down.

This was a job, she'd realised, that matched her temperament. She loved the camaraderie she shared in the mess hall with other drivers and train crew, the sense of the railway as one big family. But the solitude of the driver's cab suited her, too.

When she went over to freight, her mother had mostly worried that Heather would be lonely, driving all by herself through the night. Here in the cab, though, Heather felt empowered and trusted. She liked the idea that here, it was just her and the train.

Much as she loved rail, it was an industry where her gender set her apart. When she worked on passenger services, she'd been part of a very small minority; now, she was the only female freight driver north of the border.

There'd been a time when she hadn't dwelt much on this. Back then, Heather thought equality was about being treated the same as male colleagues. But recently she'd learned it was about much more than that.

From her window, Heather could see road traffic on M74. "You're going alongside the motorway at times and looking at the lorry drivers, feeling quite smug," she said. She marvelled at the fact that her freight train could carry 76 times as much cargo as a single HGV.

"When you see a freight train passing by, it just looks phenomenal. So to know that you're the one that's actually responsible for that…" She paused. "It's a great feeling."

Inside the cab, the number of tasks to remember was endless. It wouldn't stop, either, when she slowed the train into a station and stepped out. If she met any of her male colleagues, or saw anyone standing around on the platform, she had a checklist to go through with them too.

The railways had always been in Heather's blood. Her father, Neil, had worked on them for 45 years, as a guard and then a senior conductor at Edinburgh Waverley station. But it was her mother, Kathleen, who made her fall in love with trains.

"My dad had no sense of humour," Heather says, affectionately. "He would come home each day, very staid: 'Oh my God, this happened today.'" But Kathleen would draw out the funny side of all the stories he'd tell them about his work, and she and Heather would laugh uproariously. "My mum's Glaswegian, so she has a great sense of humour."

The family lived in a flat in Niddrie, a housing scheme on the south side of the Scottish capital. Thanks to the free passes to which family members of British Rail staff were entitled, Heather's horizons were always much broader - the Highlands, the Fife coast, across the border into England. "My mum would always take me to different places in Scotland, and I think that's where my love of the railway comes from," she says.

The passes came in handy, too, when Heather discovered she had a love of football. She supported Rangers until her hero, the winger Davie Cooper, was transferred to Motherwell; Heather cried her eyes out, then started following his new team around the country each week instead.

Cooper was deeply touched when found out about the little girl who had switched allegiances because of him - on matchdays, Heather recalls, he would give her and her mum a lift from Motherwell train station to the ground, and became a close friend of the family until his tragic death from a brain haemorrhage in 1995.

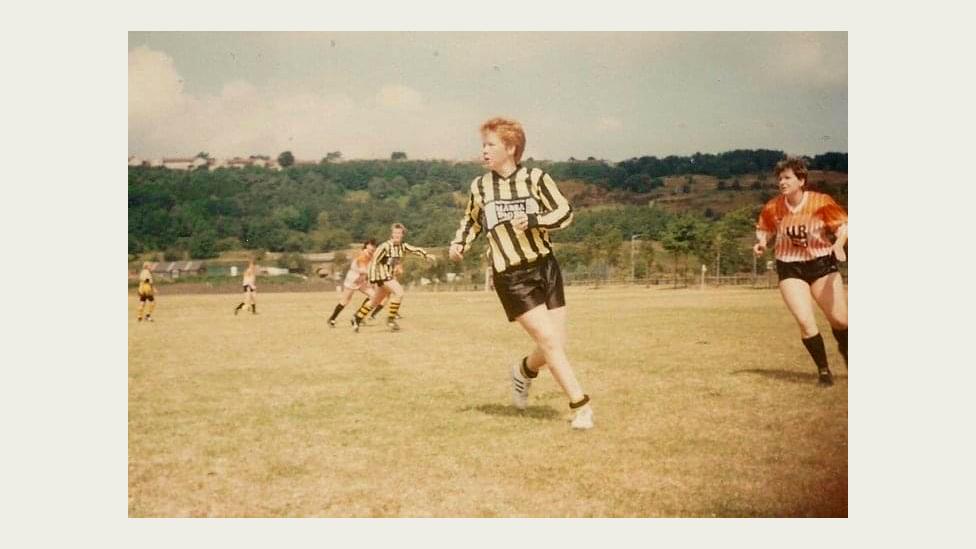

Heather had discovered she had a talent for the game herself - in lunchtime kickabouts she'd be picked ahead of most of the boys. But in those days, girls weren't allowed to play for the primary school team.

Kathleen didn't accept this. "I remember my mum leaving one day to book ballet lessons for me and coming back with my first football boots instead, saying: 'My daughter will be whatever the hell she wants to be,'" Heather recalls.

Her mum found a women's club across the city. The first team was mostly made up of adult women, but Heather stood out as a central midfielder. When she was 11 she travelled with them to Italy to play in a tournament, which they won - on their return they were met by the Lord Provost of Edinburgh and paraded through the city.

After school she joined the Royal Mail and, by the age of 20, had risen to become the manager of 100 male postal workers.

She was on the fast track to greater things, but after a decade with the Royal Mail she felt burnt out. Then she noticed a job advert - ScotRail were looking for train drivers. She knew it would be hugely competitive but she thought about the camaraderie her father, who had died the previous year, had enjoyed on the railways.

She sent in her application. The process was "like Pop Idol", Heather says - thousands of applicants, written tests, waiting in a room for her name to be called out and told she'd made it to the next stage. Eventually she was told she'd landed the job.

It took two years of intensive training to become a fully qualified train driver - first of all digesting the rulebook and safety procedures, and only after that learning to drive the train - "or more specifically learning to drive the routes, because you do need to drive them blind," says Heather.

"The level of concentration is huge," she says. "You can have 150 stations in a single shift - and if you think, 'What did I bring for my tea tonight?' you can miss the braking point for your next station."

Heather started work at a depot outside Glasgow. She loved the job immediately. There was the challenge and the satisfaction of the task itself. But there was also the bond that was formed with others doing the same, highly pressurised occupation. "There are so many things that you can do wrong, and I think that's why there's such a bond between train drivers," Heather says.

Lack of experience didn't count for much among her colleagues: a newly-qualified driver was expected to speak up and intervene if they saw one with years of experience do anything that was unsafe. "They don't see that you've only been doing the job for two minutes and they don't see you as female - they just see you as a train driver."

Nonetheless, at her depot there were 106 other drivers, and only one of them other than Heather was female.

"I probably should have been more aware of my gender, but I suppose because of my background - because I had to play football with the boys at school, because I was at Royal Mail - this, unfortunately, was my normal, so I didn't question it," she says.

Heather sat in the doctor's surgery. Everything was coloured in in neutral tones. There was a solitary window. She'd been a driver now for eight years, but she wasn't on duty at the moment. For the past month she'd been signed off from work.

Heather told the doctor about the boy who'd used her train to end his life.

She'd always known something like this could happen - drivers were warned about it in their training and would discuss it among themselves. According to Network Rail, 4.4% of suicides in Great Britain take place on the railways; there were 283 lives lost this way in 2019-20. But nothing could have prepared Heather for the reality of it actually happening to her.

She talked about how numb she'd felt ever since it had happened. How guilt had gnawed at her. All the questions she kept asking herself - could she have reacted slightly quicker? Might she have done anything to save him?

Heather told the doctor how horrific it seemed to her that anyone could do that - especially someone so young.

Where to get help

If you are struggling to cope, you can call Samaritans free on 116 123 (UK and Ireland), email jo@samaritans.org, or visit the Samaritans website, external to find details of the nearest branch.

BBC Action Line has details of organisations offering information and support if you, or someone you know, has been affected by mental health issues.

"Actually," the doctor said, "You'd be surprised at the problems we see with men and boys."

He was talking about mental health. The doctor's answer saddened her, but having spent her entire career working in heavily male-dominated environments, Heather understood what he meant.

"Something I'd picked up on is that men don't talk about simple things," Heather says. "It's not that men have more problems than women, or worse problems. We all have problems. But women deal with the smaller ones through talking."

Heather was signed off work for three months. Her employers supported her - she was sent for counselling and hypnotherapy. One of the things that helped her most was the support she received from colleagues. "Big, hard, burly men, who don't show their emotions, rang me up to say: 'I've been through this too, I'm here for you,'" she says.

When she returned to her duties, she knew she wasn't quite the same person that she had been before. She was more irritable, less patient than she used to be. She couldn't watch television crime dramas or anything violent that might remind her of what she'd witnessed.

"A relationship that I'd been in for probably 19 or 20 years ultimately came to an end," she says. "And I can now look back and recognise that part of that was as a result of me changing."

A few years later she saw another job advert, this time with Freightliner. Moving into freight was a greater technical and professional challenge; what's more, it offered a rota without weekend shifts.

But the gender dynamics were even more stark. At ScotRail female drivers were a small minority, but there were also women guards and ticket examiners. "Now I am entirely surrounded by men," she says.

Historically, freight had been widely regarded - inaccurately, Heather quickly discovered - as dirty, heavy, physically draining work, and the workplace was exclusively male as a result. "In this day and age, you don't expect to be the only woman," she says. "Even with my background, it was intimidating."

To her surprise, her new colleagues were overjoyed to have her on the team. They'd look forward to her being on shift - not because they wanted to chat her up, but because they could open up to her about their problems in a way they wouldn't with other men, Heather found. "I've had conversations with colleagues where I know I'm the first person they've had that conversation with," Heather says.

All this made her rethink her long-held idea that being treated equally in a male-dominated environment required her to keep her head down and not ask for any special treatment. "I realised that it's important that you don't shy away from being a woman," she says. "Diversity is about bringing different energies into the room."

It also brought home to her once again the lack of opportunities men were given to talk about their mental health. She'd never stopped wondering about the boy that her passenger train had struck.

"I always think back to: Was that young boy showing signs? Could somebody have seen those signs?" Sometimes she would visit the town he had grown up in. She'd see young men who would have been around his age and now had families of their own. It brought home to her again the terrible meaning of a young life lost.

Then Heather learned of a course run by the Samaritans charity in partnership with Network Rail. It was called Managing Suicidal Contacts and was offered to all rail industry staff and British Transport Police officers - some 22,000 people had taken it since it was launched.

Its purpose was to teach them to identify people on the railways - whether passengers, passers-by or fellow employees - who might be vulnerable to suicide, and then how to approach them.

To Heather, it was a massive eye-opener. "It's teaching staff to recognise what is out of the ordinary," she says. "As human beings it's our job to go and take five minutes to speak to somebody and say, 'Are you OK?'" she says.

Since then, she says, "I've approached people numerous times - you do become aware of when something isn't quite normal, there are danger signs you can see." These include unusual body language, staring straight ahead or at the track, and standing somewhere on the platform where you wouldn't normally go if you were planning to board a train.

It didn't take much to notice when she was getting through. "Sometimes you'll be sitting having a chat with someone - a really basic chat - and you'll see the weight of the world lifted from them." She'd think back to the boy who died, and wonder if talking could have helped him too.

The evening light was fading as Heather approached Carlisle. She eased the locomotive alongside the platform until it came to a halt.

The cargo would carry on towards the ports of the south of England. But Heather's shift was over. It was time to hand over to another driver.

Afterwards, she'd make her way home to Airdrie in Lanarkshire. A few years ago her mum, who is now 80, moved in with her. Kathleen was recently diagnosed with Alzheimer's Disease, but her sense of humour is very much intact.

"We still have great laughs - she's still got a crazy Glaswegian sense of humour, absolutely loves that I'm on the railway. And that I come home with all these stories," Heather says.

"And she's got a photograph of me driving a freight train up on the mantelpiece, which she insists everyone who walks in the room takes a look at."

Before the journey home, Heather watched the freight train she'd driven leave the platform. It rumbled away from the station and into the night.

Follow @mrjonkelly, external on Twitter

Photos by Emma Lynch/BBC

You may also be interested in...

Loretta Harmes hasn't eaten for six years, but she hasn't lost her passion for cooking. Even though she cannot taste her recipes, she has a growing following on Instagram, where she's known as the nil-by-mouth foodie.