'A meme that almost made me quit my family WhatsApp group'

- Published

Indian family WhatsApp groups are often sad places at the moment, as Covid continues to cause thousands of deaths per day in the country. But in families so far untouched by the crisis, edgy jokes and memes are sometimes causing tensions, says BBC gender and identity correspondent Megha Mohan.

As my finger hovered over the "exit group" button, it occurred to me that this was the first time I'd seriously contemplated leaving the extended family WhatsApp group. Although I frequently and guiltlessly duck out of groups that outlive their purpose, none of them have ever included anyone I'm related to.

Can you try to imagine how noisy a group with active outposts in three continents can be? It's even noisier than you're thinking.

Content is shared daily, over different time zones. As the India-based delegation goes to sleep, the American battalion takes over to ensure a steady flow of memes, videos of the nieces and nephews and occasional punditry over global events (elections, say, or celebrity divorces).

I'm largely a responder, regularly dispensing heart emojis over photos of the children and pets of the family. I don't usually start a conversation. Until a couple of weeks ago, that is, when I shared a photo of the arresting cover of the New York Times on 26 April into the family group.

It had India's Covid as its top story, accompanied by an aerial shot of dozens of burning funeral pyres watched by a handful of mourners in protective gear. The headline read, "Cremations Never End". Another family member followed with a link to an Australian article that accused Prime Minister Modi of leading India into what it called "an apocalypse".

This was when a cousin living in India piped up.

"Every country has suffered and no government has managed it successfully," he wrote. "And the media is mostly biased... media across the globe have their own agenda."

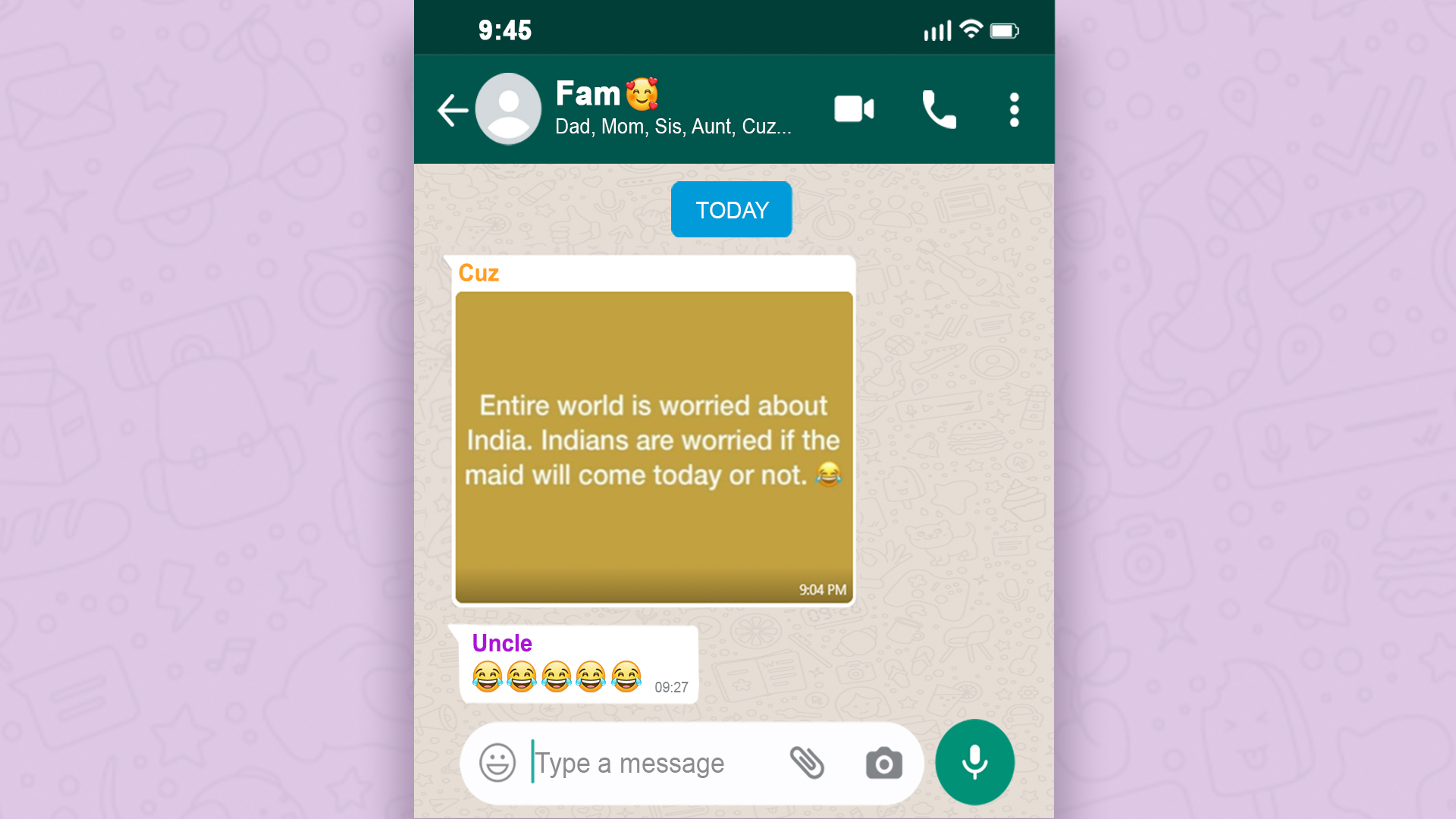

Another cousin chimed in with a meme. It read: "Entire world is worried about India, Indians are worried if the maid will come today or not." A laughing yellow emoji face with tears ejecting from its closed eyes accompanied the text.

I started to feel the rage that bubbles from spending too long on social media.

Here I was, looking down at my phone from my flat in London, vaccinated, and furious that my family in India were sending memes and having a go at me. (As a journalist, I decided to take that observation of a biased media personally.)

The headlines in the UK were dominated with war-like images from hospital wards, a plea for oxygen, thousands of daily deaths, a peak not in sight.

My family, all university educated and middle class, had thankfully not been touched by the virus. Many headlines suggested that India's Covid crisis had left the poor especially vulnerable - though of course many wealthy people have reported not being able to get hospital beds, including a former Indian ambassador, Ashok Amrohi, who died in a hospital car park last month as he waited for one.

According to the National Domestic Workers Movement, more than four million people are employed as domestic helpers in more affluent homes like my family's, but unofficial estimates put that number at 50 million. My colleagues reporting in Delhi said the vast majority of these workers had been let go by employers and many weren't being paid. A Delhi-based NGO Action Aid estimated that 80% of the informal workforce, external in India had lost their jobs since the pandemic was declared.

Which is why the maid meme irked me especially. And just in that moment I saw a tweet from a New York-based writer: "I'm just about ready to leave the Desi family WhatsApp group," it read. "The Covid jokes are going over my head."

After a brief search on social media I came across a number of WhatsApp users who were not connecting with their family's Covid jokes, most of them Indian. India is WhatsApp's largest market, with around 340 million active users. Indians also make up the world's largest diaspora, according to the UN, with 18 million people from Indian families living abroad.

"It has a lot to do with difference in perspectives," says Dr Charusmita, a researcher in media studies who lives in Delhi. "Had that meme been sent to another middle-class person living in India, they would have most likely seen it differently. It is not to dehumanise the house-help but to highlight, and often to mock, their own privilege. For some, it is a fairly innocent way to find some levity amidst a large-scale catastrophe.

"Some relate to such humour circulating across WhatsApp groups, and some find it disgusting."

But people who live in the country don't take kindly to being reminded of this difference in their lifestyles and values, she says, as they find it patronising.

Dr Charusmita told me that she'd been sent several Covid-humour memes, including cartoons of people taking selfies with dying patients - a commentary on how death was now a commodity for social media. There are milder versions of everyday lockdown humour too that invite less heat in the WhatsApp family groups. One showed a photo of Prime Minister Modi performing the Yoga one-nostril breath, the Nadi Shodhana Pranayama, with a comment saying "Modiji breathing from one nostril so others get more oxygen."

I found four Indian meme-sharing Telegram channels, two with over 100,000 subscribers, sharing hourly jokes about Covid.

"There's been a lot of reporting of misinformation being rife in Indian WhatsApp groups, but not so much about the gallows humour in there," says Dr Rohit Dasgupta from the University of Glasgow, who specialises in Indian digital culture. "When we laugh, there's hope, and the hope deflects from the pain."

Some pain also comes from a frustration of being perceived as a third world country when just a few weeks ago, India was a major exporter of the AstraZeneca vaccine. According to the Indian government more than 90 countries (from Syria to the UK) have received vaccines made in India, which totalled at more than 60 million doses.

"There's pride there too," says Dr Dasgupta. "Although it's clear that India needs help, Indians living in the country want you to know that they can also help themselves."

Later the purveyor of the maid meme, my cousin in Kerala, messaged me privately to clarify that he had definitely not intended any disrespect towards Indian maids. It was a joke, he said, maybe not even a very funny one, that was pointing to a more hopeful future, where familiar routines would return. Life wasn't routine right now. It was almost two o'clock in the morning in India and he'd just got back from a shift in a hospital where he works as a frontline doctor, tending to patients with Covid.

I then spoke to a journalist in Delhi, who said his WhatsApp groups in recent weeks had turned into a "graveyard announcement", where friends posted obituaries of family members or made pleas asking for help to find hospital beds for people they know who were affected. The conversation on the ground with Indian residents, he said, was sombre.

I didn't leave the family WhatsApp group, of course. Someone shared images of one of the kids who had decided to conduct a fashion photoshoot while cleaning out a cupboard and dozens of heart emojis flooded the screen. We moved on.

Dark Humour

A 2012 study on Dark Humour in Psychological Science explained it using the "benign-violation theory" - suggesting that people are amused by moral violations and threats to their normal world views, but only as long as they are harmless

A 2017 small-scale study of 156 people in the journal Cognitive Processing found that people with a higher IQ appreciated dark jokes more

A 2003 study in the International Journal of Emergency Mental Health found that dark humour employed by first responders had an overall beneficial effect on patients

Follow Megha Mohan on Twitter, external and illustrator Aishwarya Mullamuri on Instagram, external