'My night in Quisling's cabin'

- Published

Would you rent a holiday cabin that was built for a notorious Nazi collaborator? Perhaps surprisingly, it's something you can do in Norway - and few people seem to mind. Scottish novelist Ben McPherson, who lives in Norway, found this lack of fuss hard to understand. So he went to investigate.

I think I might be annoying my Norwegian wife. "Don't you think it's weird," I say, "that I can just rent his cabin?"

My wife eyes me warily. She's the one who told me about the cabin. Now I'm accusing her country of a moral failing.

"It's just a cabin," she says cautiously.

"It's Quisling's cabin," I say.

When Norway was invaded by German forces in 1940, Vidkun Quisling was delighted to see them. He had based his National Union party on the Nazis, and was duly installed as a puppet leader by the occupiers. His name gave us the English word "quisling": it means a lackey, a traitor, a bootlicker. So surely his cabin should be off limits to visitors?

Britain may be tearing itself apart over what to do with controversial statues, but Norwegians are often more relaxed about Nazi buildings. "Here's the difference between Norway and Britain," my wife says. "People here really don't see a cabin as evil."

The summer cabin is where Norwegians go to relax, and it enjoys an almost religious status - a place to fish, to gather berries, to chop wood. Enkelt og greit, people say - simple and good. It's all about reconnecting with nature, physically and emotionally.

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service, or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

In his time Quisling was viewed as a dashing, heroic outdoor type. To modern eyes that's hard to understand: in his crumpled suit, with his neat side parting, he looks like a filing clerk. We don't see the tall, blond soldier and man of action some saw then. Quisling even managed to convince Hitler that he represented an ideal of Aryan manhood. In 1942, the Nazis installed him as prime minister. Once in power, he oversaw the deportation of a third of the country's Jews to extermination camps. Most of the rest escaped to other countries.

Vidkun Quisling in 1942

Quisling commissioned his cabin as a sauna, but no-one seems to know when. It's a traditional little structure made of dark wood logs, with grass growing from the roof for insulation. He never got to use it, though. The war ended before he could fire up the coals, and he was executed by firing squad - a true quisling's death.

Modern Norway is the kind of rights-based social democracy Quisling would have hated, with a progressive attitude to gay rights and a large immigrant population. Now a new generation has started asking difficult questions about the country's wartime past, yet until very recently the war stories people wanted to hear emphasised Norwegian heroism and resistance. Quisling was simply not part of the national conversation. Still, in what possible world do you turn the sauna cabin of a collaborationist leader into a tourist destination?

"I want to understand," I say to my wife.

"Then go and stay there," she says. "See for yourself."

"Do you want to stay there with me?" I say.

"No."

But she doesn't object when I suggest taking our 12-year-old son. And so I book, and we go. There it is, on an island, a simple log cabin on a rise overlooking the fjord. It's pretty from a distance; you'd never know that it was built by a murderous, unapologetic Nazi.

"A national romantic experience," says the description from the people who rent it out. "One room. Sleeps four." I can't find any reference to Quisling in their publicity material. They're not trying to profit from the association, but you really could rent it and not know.

My English friend Nick took his two young children to stay there. By mistake. "I just thought, nice little place, lots to do," he tells me. "They loved the little beach. There are ducks and goats. It was great, before you told me what it was."

Not every Norwegian sees "Quisling" as a synonym for traitor. To Anders Behring Breivik, who murdered 77 people in 2011, he was a role model. That chilling little phrase - a "national romantic experience"... might some not see Quisling's cabin as a shrine?

My wife thinks that using it as a cabin diminishes its power. When I ask Thorgeir, a Norwegian friend, what he thinks, he agrees. "It's a perfectly good cabin. Be wrong to burn it to the ground."

Will there be an atmosphere, I wonder? I want to see how my Norwegian son reacts.

But… Quisling's cabin is unexceptional. Yes, there's the image of a woodcutter carved into the front door, and yes, it's the kind of Nordic folk art the Nazis loved. But ordinary Norwegians like wood carvings too.

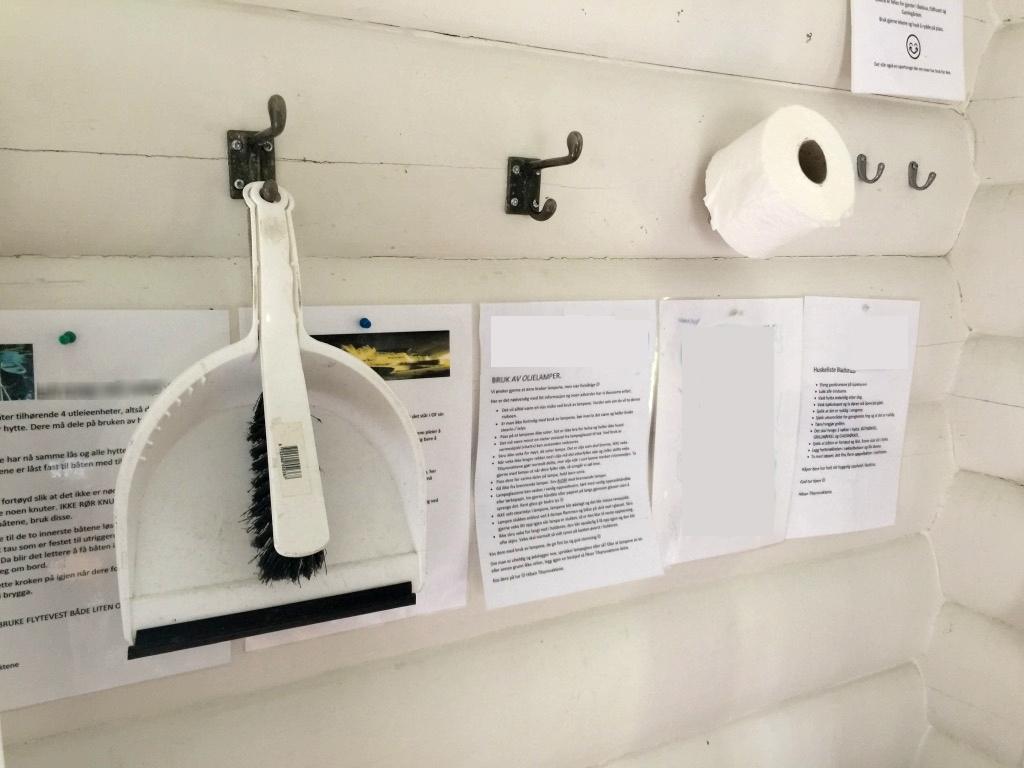

Inside, the woodwork is clean, white-painted. There are cheerful carvings of crabs and crayfish in the kitchen area, and shelves full of cleaning products and insect sprays. A toilet roll hangs on the wall beside a dustpan and brush, for use at the outside toilet.

My son ignores my brooding over the history this place represents; he spends his time playing football with the children in the nearby cabins. I photograph the interior, or sit trying to find this building's dark soul. I can't.

No-one arrives on a nationalist pilgrimage, at least while we are there.

When night comes, my son and I sleep easily in our wooden bunk beds. Still, we leave early the next morning.

My wife ruffles our son's hair. "How was the cabin?" she asks.

"Boring," he says. "What's for breakfast?"

Vidkun Quisling would have hated that.

All photographs by Ben McPherson

You may also be interested in:

When Alexander Bodin Saphir's Jewish grandfather was measuring a high-ranking Nazi for a suit in Copenhagen in 1943 he got an important tip-off - the Jews were about to be rounded up and deported. It has often been described as a "miracle" that most of Denmark's Jews escaped the Holocaust. Now it seems that the country's Nazi rulers deliberately sabotaged their own operation.