How Norway is offering drug-free treatment to people with psychosis

- Published

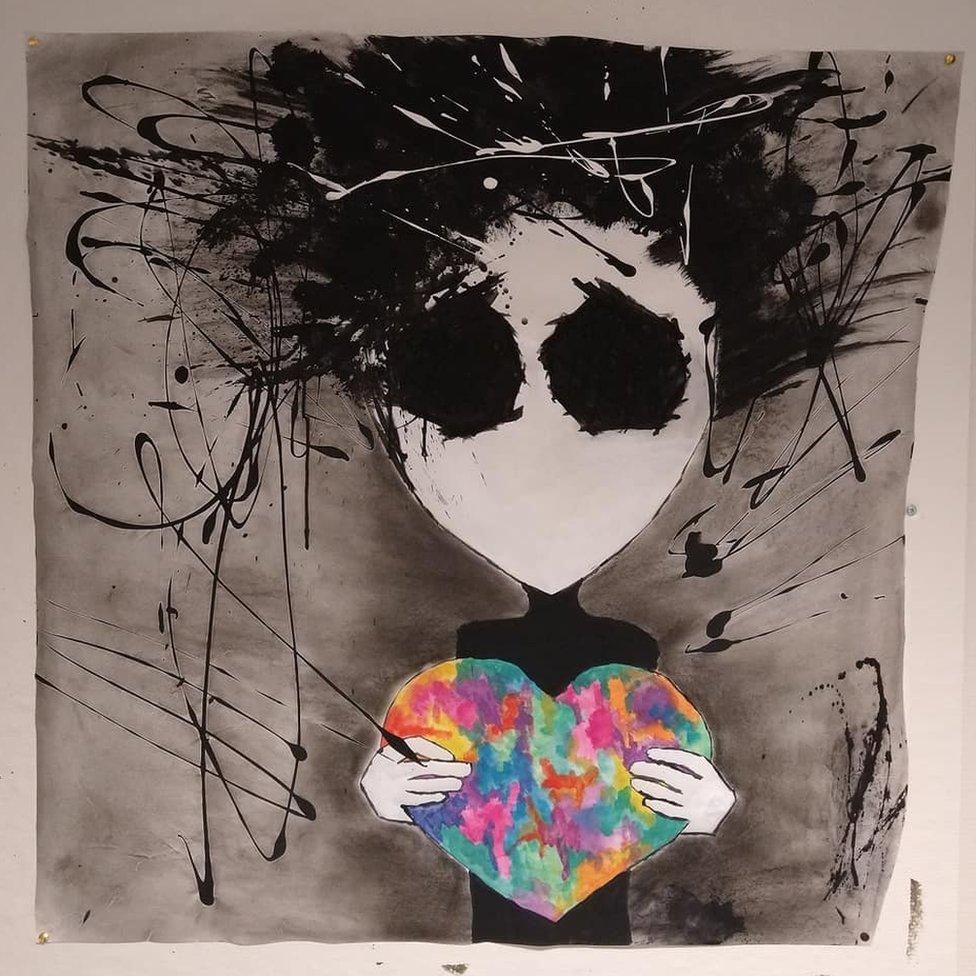

Art therapy helps Malin manage her condition

Most people with psychosis take powerful drugs to keep delusions and hallucinations at bay - but the side-effects can be severe. In Norway, a radical approach is now on offer via the national health system for patients who want to live drug-free.

Malin was 21 when her life began to unravel.

She had struggled with severe depression and low self-esteem since she was a teenager.

Then a voice inside her head started telling her she was fat and worthless - and that she should kill herself.

"He became very angry. He kind of isolated me because he got a lot of power. Eventually I also starting seeing things, like tentacles coming out of the walls," she says.

Malin left her small home town near the fjords of northern Norway and went off to university. But it wasn't long before she had a complete breakdown that left her unable to get out of bed. Her family came to pick her up and soon she was committed to a psychiatric unit where she stayed for a year. It was the first of several long stays in psychiatric hospital wards where powerful anti-psychotic medication was the only treatment on offer.

"I was so full of drugs, my mind was just a blur. I just sat there passively watching my life go by with no connection to my emotions or feelings.

"And it's kind of been the same thing over and over. I've sought help and what they can give me is medication. And nothing really got any better.

"It's quite devastating. You just really want to get well. And people tell you that now this is your life, you should be content. And I cannot be content with this life."

Malin's experience with psychiatric medication isn't unusual. Although many people with psychosis find anti-psychotic drugs enable them to live a normal life, it is thought around 20% of patients do not respond well. The side effects can be life-changing - extreme fatigue, weight gain, increased cholesterol and diabetes.

In Norway, concerns about the overall benefit of these drugs are compounded by a long-standing problem with forced treatment, which is more common here than in many other countries according to the limited number of international comparisons that exist.

The UN Committee Against Torture has singled out Norway's use of forced isolation in mental health facilities as something that must change.

Like Malin, Mette Ellingsdalen was given anti-psychotic drugs during a period of 13 years when she suffered severe depressions - as a result of bipolar disorder - and was unable to care for herself. Unlike some of her fellow patients, she wasn't physically held down and injected with the drugs, but she still felt coerced; if she had refused the medication, she wouldn't have been admitted to hospital.

"I did have a big crisis that brought me into the system, things from my childhood that I struggled with strongly. The medication numbed some of the symptoms, but they also numb your own power and your own ability to deal with yourself. I lost my own story somehow," she says.

Eventually, after five years of trying but failing to live without medication, she was able to successfully taper off her drugs and in 2005 she joined the movement to change Norway's mental health system and is now chair of the patient user group, We Shall Overcome.

"The most easy way to reduce force is to give people a choice, to give them a treatment they can say yes to," she says.

Years of advocacy work by people like Mette paid off in 2016 when regional health authorities were ordered by health minister Bent Hoie to provide medication-free treatment wards. While medication-free treatment is available in some other countries, Norway became the first country in the world to embed it as an option in the state-run mental healthcare system.

At the time, Dr Magnus Hald was director of mental health and substance abuse at the University Hospital of northern Norway based in Tromso, Norway's gateway to the Arctic. He'd worked for years in units where a lot of drugs were used and was keen to explore an alternative treatment - so he took on the job of running the hospital's new drug-free department.

"To me, the most important thing is that people are allowed to try different kinds of possibilities," he says.

"You have to tell the truth to the patient about how the medication works and what you know about it. And it seems that in co-operation with the pharmaceutical industry, they've told people things that are not completely correct about how medications work and what the risks are. For instance, there is a myth that there is some kind of chemical imbalance in the brains of people with serious mental problems [and] there is actually no research that really supports this."

Many of the patients at the unit in Tromso are tapering off drugs, which takes time and care.

"For most of the patients that we have, it works," says Hald. "Some patients will never go back to using any kind of drugs. And some patients might go back to drugs after some time and some patients may just reduce their doses."

Malin, now 34, is a patient at the unit.

She spends several weeks at a time in Tromso and then goes home for months in between, back to her dog, Jarek. It's not easy - she lives alone and has little mental health support nearby so her progress is slow - and the voice she hears has not completely disappeared.

Malin now mainly uses medication to calm her at night. She's going through intensive therapy while at the unit, an option she says she was never offered while on medication. Art has been central to her recovery.

"I'm trying to reconnect with my emotions instead of dulling down the symptoms. We explore what this voice wants and what do I need for him to stop?"

Malin now feels strong enough to think about working, hopefully in Norway's husky dog sledding tourism industry.

"I feel like for the first time ever I'm starting to find myself. I'm starting to build up my self-esteem and I can dare to feel some hope for the future, and that is pretty amazing."

Stories like Malin's are starting to be heard - and really listened to. But medication-free treatment is controversial in Norway.

For many patients, anti-psychotics are vital. Claudia (not her real name) now in her 20s, first became suicidal and delusional as a teenager. Part of her illness was believing the anti-psychotics she was offered were poisoned. So she was held down and forced to take them - and got better.

"But then after a period of stress, again, I got really sick, and had to start again. And now I've sort of come to terms that I need medication to at least keep my head above water.

"I don't really like the word 'normal', but I feel really good when I'm on medication. I feel like I can contribute during my studies, and hang out with friends and stuff like that, while when I'm off them, my functionality is just declining and I feel more stressed and chaotic and weird."

Critics say the medication-free movement is driven by ideology rather than evidence. Dr Jan Ivar Rossberg, a psychiatrist who lives and works in Oslo, likens it to failed experiments in the 1960s and 70s when patients were given free rein in therapeutic communities, encouraged to take LSD and regress to childhood. This methodology was called "anti-psychiatry".

"History has shown us that this approach doesn't work, so we have stopped using it. We don't have treatment approaches shown to be effective without medication," he says.

He points to evidence that shows the best outcomes for people with psychosis involve medicating through the initial acute phase, when delusions and hallucinations are strongest, and staying on the drugs for around two years before trying to taper down to a lower dose.

Magnus Hald is not convinced by this. He is about to start a research project to track patients in the years after they've been at the medication-free unit in Tromso. There have been no suicides among his medication-free patients, but so far the approach lacks a strong evidence base.

The doors of the drug-free treatment department at Magnus Hald's hospital are not locked

"The idea of evidence-based medicine is difficult within mental health as a whole, although it's of course an aim that we should have," he says. "At the same time, we know that diagnoses in psychiatry are just a classification system. Even though you give a person a diagnosis of schizophrenia, you do not see any malfunction in the brain besides what you experience by engaging in a conversation with the person. You cannot see anything on the CT or the MRI images."

There is controversy also about how the medication-free programme could develop in future.

So far, patients in the acute stage of psychosis cannot be referred to medication-free units. User groups are hoping to change that, arguing that this phase often passes on its own if people can be in a place of safety and support while they weather the storm.

But Dr Tor Larsen, a specialist in acute psychosis, worries about this idea. He points out that most patients with untreated psychosis do not realise they are ill so will not agree to be treated with or without drugs - and drug-free units operate on a voluntary basis.

"It's almost by definition a part of having hallucinations or delusions that you don't think you're sick, if you are in contact with God or if you think you are the reborn Napoleon," he says. "So in cases where people have devastating psychosis, it might be important to give them treatment even on an involuntary basis."

Studies show many people with untreated psychosis end up living on the streets, he says, and that about 30% of patients with untreated psychosis commit crimes or are violent towards relatives and others.

There is also an increased rate of homicide.

He cites as an example the random murder of 67-year-old Bjorg Marie Skeisvoll Hereid in a graveyard in 2019 by a psychotic man with an axe. The murder shook the quiet town of Haugesund in the south-west of Norway and made national headlines.

The murderer wasn't on a drug-free treatment programme, but he had chosen to come off his medication, and was also using illegal drugs. The tragic incident sparked debate about a change in the law made in 2017, which states that patients who are able to make decisions about their own treatment can no longer be involuntarily committed or forced to take medication, unless they pose an imminent risk. Critics say this has made it more difficult for doctors to commit potentially dangerous people to hospital for treatment.

Malin has titled this painting "Hopeless"

Hakon Rian Ueland, 54, one of the campaigners who helped bring about medication-free treatment in Norway, believes that this conversation about danger hides an agenda to shelter society from the often challenging behaviour of people going through psychosis. "They are putting forward an agenda to sedate people," he says, adding that symptoms that alarm neurotypical people may be important for the person experiencing them. "When you go through psychosis it can be very dramatic."

He says there are still bureaucratic and cost barriers to people who want to access the medication-free services.

"The whole movement needs more oversight," he says. "We need a review of what has happened so far. I would like to see someone who goes in from outside the system and has the power to ask for change."

Psychiatrists and patients around the world are watching what happens in Norway, where the government has taken decisive action to try and improve the lives of psychotic people by giving them more power over their lives. Globally, there's a reassessment of the way people with mental illness are treated and a will to reduce coercion.

Medication-free treatment could be just another therapeutic fad - or it could have the power to change psychiatry for good.

You may also be interested in:

Branka and Drazenko outside the Cepin asylum, now closed

In Croatia, thousands of people with mental illness live in institutions. The process of moving patients out of residential care and into the community happened decades ago in many European countries. But Croatia has resisted change - except in one region in the east of the country, close to the Serbian border.