Smart vision for mobile phones in the developing world

- Published

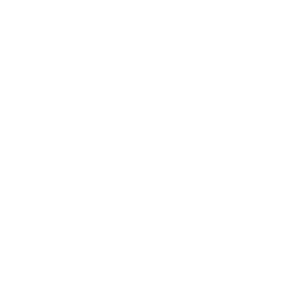

Jonathan Fildes takes an eye test with the snap-on lens for a mobile phone

Twenty years ago a mobile phone was a mobile phone. It made calls and little else.

Now, handset makers are remiss if they don't pack a camera, accelerometer or gyroscope into a phone's innards.

As a result of their increasing sophistication, phones have become serious bits of kit.

So serious, says Professor Ramesh Raskar of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Labs, that - with a few tweaks here and there - they could begin to replace expensive scientific and medical equipment.

"This is just a new way of thinking about scientific instruments," he told BBC News.

In particular, he says, phones come into their own in developing countries where there is a shortage of lab equipment, but an ever increasing number of mobile users and connections.

"People who make a dollar a day have a cellphone, which is just mind-blowing if you think about it," he said.

The UN estimates there are around 5 billion mobile subscriptions, with most growth in the developing world and particularly Africa.

But those same areas often have little access to healthcare and medical equipment.

The World Health Organization recently held a meeting to discuss the problem and the "uneven and unfair distribution" of medical devices.

For Professor Raskar and others the solution in many cases is obvious: the mobile phone.

Eye phone

His interest lies with building devices that use the new high-end screens found on many phones.

In the last two years alone, he says, the resolution of these devices has increased six fold, with some now boasting over 300 dots per inch (dpi).

The technology is currently being tested in India and the US

"At that resolution you can start doing things that you can only do with high-end scientific instruments," he said.

He is working on a device called the Near Eye Tool for Refractive Assessment (Netra), a cheap clip-on gadget, which can be used to diagnose eye conditions such as nearsightedness and farsightedness.

"Look through it and it gives you your prescription," he said.

When a person looks through the clip-on lens, attached to the front of the display, they are presented with two lines - one red, one green - on the phone's screen.

If they are aligned, their vision is fine. If not, the person taps the phone cursor buttons until they come together.

Repeating the test in different configurations reveals how their eyes focus and what corrective lenses they may need.

There are currently more than 2 billion people who have refractive errors, he said, over a quarter of which go untreated.

"Clearly in developing countries this seems like an ideal solution," said Professor Raskar.

He said there were currently two methods commonly used to test people's eyes; expensive laser techniques and more traditional reading charts.

"[Reading charts] seem like a low cost solution but it is not because the person must carry a set of trial lenses with them," he said.

He is currently running trials of the device in Hyderabad in India, as well as hospitals in Boston.

Shadow tricks

But Professor Raskar is not alone in his efforts to put mobile phones centre stage in labs around the world.

Cellophone is based on technology known as Lensless Ultra-wide-field Cell

In California, Professor Aydogan Ozcan, assistant professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), is working on a mobile replacement for the microscope.

He is building the Cellophone, a handset modification that allows it to detect microbes and bacteria in fluid samples.

"It's suitable for field use and for global health challenges," he told the BBC.

The main difference to a traditional microscope is that it is entirely lens-free.

"We get rid of one of the most expensive components by replacing it with computer code," he said. Specifically, he has written so-called "reconstruction algorithms" to process the images.

Samples of blood, urine or saliva can be loaded into the phone "as though you are sliding in a memory stick", he said.

Instead of imaging the cell or bacteria through a series of lenses that magnify the sample, the device records the shadows of the cells or bacteria to be imaged.

"Unlike our own shadows on the street, the shadows of micro scale bacteria contain a unique texture from which you can identify it and reconstruct an image," he said.

Images are captured using a special light source and the phone's camera. These can then be sent by multimedia message to a laptop to be processed, with the results sent back as a text.

However, as smartphone processing power increases, he said, it will be possible to process the image in-situ.

He is currently refining the technology to detect the parasite responsible for malaria and hopes to roll-out trials soon.

Be prepared

Professor Ozcan said the mobile was an obvious choice for his work

"It is such a broad platform," he said. "It's a great means of bringing advanced computation to people's fingertips."

Many others share his vision. Engineers around the world are tinkering with handsets, building hardware and software designed to get them out of pockets and into the lab.

Professor Peter Bentley from University College London on the iStethoscope that monitors heartbeats through a phone.

Recently, a computer scientist grabbed headlines after he wrote an app for the iPhone which converted it into a stethoscope.

A firm in the US called AgaMatrix has submitted its design for a blood glucose monitor that plugs directly into a phone to the Food and Drug Administration for review.

And down the road from Professor Ozcan, researchers in Berkeley are building the CellScope, a small microscope that can be clipped on to a camera phone.

This flurry of activity suggests there could be a new wave of healthcare, very different to today's existing services, and of mobile development, said Professor Raskar.

"Right now we are very familiar with the notion of software apps," he said.

"I believe soon there will be hardware app stores where you buy a $1 or $2 clip-on for your phone," he said.

"Those clip-ons will enhance your phone if you want to measure the quality of the milk you are buying, the quality of your water, or measure your blood pressure."

It is a vision shared by Professor Ozcan.

"The cellphone holds huge promise," he said. "It has become like a Swiss-army knife," he said.

- Published21 September 2010

- Published15 September 2010

- Published2 September 2010