Stuxnet worm 'targeted high-value Iranian assets'

- Published

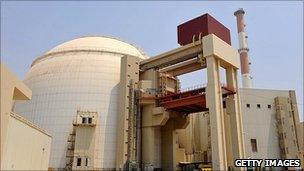

Some have speculated the intended target was Iran's nuclear power plant

One of the most sophisticated pieces of malware ever detected was probably targeting "high value" infrastructure in Iran, experts have told the BBC.

Stuxnet's complexity suggests it could only have been written by a "nation state", some researchers have claimed.

It is believed to be the first-known worm designed to target real-world infrastructure such as power stations, water plants and industrial units.

It was first detected in June and has been intensely studied ever since.

"The fact that we see so many more infections in Iran than anywhere else in the world makes us think this threat was targeted at Iran and that there was something in Iran that was of very, very high value to whomever wrote it," Liam O'Murchu of security firm Symantec, who has tracked the worm since it was first detected, told BBC News.

Some have speculated that it could have been aimed at disrupting Iran's delayed Bushehr nuclear power plant or the uranium enrichment plant at Natanz.

However, Mr O'Murchu and others, such as security expert Bruce Schneier, external, have said that there was currently not enough evidence to draw conclusions about what its intended target was or who had written it.

Initial research by Symantec showed that nearly 60% of all infections were in Iran, external. That figure still stands, said Mr O'Murchu, although India and Indonesia have also seen relatively high infection rates.

'Rare package'

Stuxnet was first detected in June by a security firm based in Belarus, but may have been circulating since 2009.

Unlike most viruses, the worm targets systems that are traditionally not connected to the internet for security reasons.

Instead it infects Windows machines via USB keys - commonly used to move files around - infected with malware.

Once it has infected a machine on a firm's internal network, it seeks out a specific configuration of industrial control software made by Siemens.

The worm searches out industrial systems made by Siemens

Once hijacked, the code can reprogram so-called PLC (programmable logic control) software to give attached industrial machinery new instructions.

"[PLCs] turn on and off motors, monitor temperature, turn on coolers if a gauge goes over a certain temperature," said Mr O'Murchu.

"Those have never been attacked before that we have seen."

If it does not find the specific configuration, the virus remains relatively benign.

However, the worm has also raised eyebrows because of the complexity of the code used and the fact that it bundled so many different techniques into one payload.

"There are a lot of new, unknown techniques being used that we have never seen before," he said These include tricks to hide itself on PLCs and USB sticks as well as up to six different methods that allowed it to spread.

In addition, it exploited several previously unknown and unpatched vulnerabilities in Windows, known as zero-day exploits.

"It is rare to see an attack using one zero-day exploit," Mikko Hypponen, chief research officer at security firm F-Secure, told BBC News. "Stuxnet used not one, not two, but four."

He said cybercriminals and "everyday hackers" valued zero-day exploits and would not "waste" them by bundling so many together.

Microsoft has so far patched two of the flaws.

'Nation state'

Mr O'Murchu agreed and said that his analysis suggested that whoever had created the worm had put a "huge effort" into it.

"It is a very big project, it is very well planned, it is very well funded," he said. "It has an incredible amount of code just to infect those machines."

His analysis is backed up by other research done by security firms and computer experts.

"With the forensics we now have it is evident and provable that Stuxnet is a directed sabotage attack involving heavy insider knowledge," said Ralph Langner, an industrial computer expert in an analysis he published on the web, external.

"This is not some hacker sitting in the basement of his parents' house. To me, it seems that the resources needed to stage this attack point to a nation state," he wrote.

Mr Langner, who declined to be interviewed by the BBC, has drawn a lot of attention for suggesting that Stuxnet could have been targeting the Bushehr nuclear plant.

In particular, he has highlighted a photograph reportedly taken inside the plant that suggests it used the targeted control systems, although they were "not properly licensed and configured".

Mr O'Murchu said no firm conclusions could be drawn.

However, he hopes that will change when he releases his analysis at a conference in Vancouver next week, external.

"We are not familiar with what configurations are used in different industries," he said.

Instead, he hopes that other experts will be able to pore over their research and pinpoint the exact configuration needed and where that is used.

'Limited success'

A spokesperson for Siemens, the maker of the targeted systems, said it would not comment on "speculations about the target of the virus".

He said that Iran's nuclear power plant had been built with help from a Russian contractor and that Siemens was not involved.

"Siemens was neither involved in the reconstruction of Bushehr or any nuclear plant construction in Iran, nor delivered any software or control system," he said. "Siemens left the country nearly 30 years ago."

Siemens said that it was only aware of 15 infections that had made their way on to control systems in factories, mostly in Germany. Symantec's geographical analysis of the worm's spread also looked at infected PCs.

"There have been no instances where production operations have been influenced or where a plant has failed," the Siemens spokesperson said. "The virus has been removed in all the cases known to us."

He also said that according to global security standards, Microsoft software "may not be used to operate critical processes in plants".

It is not the first time that malware has been found that affects critical infrastructure, although most incidents occur accidentally, said Mr O'Murchu, when a virus intended to infect another system accidentally wreaked havoc with real-world systems.

In 2009 the US government admitted that software had been found that could shut down the nation's power grid.

And Mr Hypponen said that he was aware of an attack - launched by infected USB sticks - against the military systems of a Nato country.

"Whether the attacker was successful, we don't know," he said.

Mr O'Murchu will present his paper on Stuxnet at Virus Bulletin 2010 in Vancouver on 29 September. Researchers from Kaspersky Labs will also unveil new findings at the same event, external.

- Published17 June 2010

- Published16 August 2010