The ultimate DIY computer project

- Published

A lot of wire wrapping went into the Magic-1 homebrew CPU

Some people like to build their own computers. A smaller number like to modify them to boost the speed of the processor and make them more powerful.

Then there is an elite for whom building a modern PC is mere tinkering. Instead, they opt for the much more difficult task of building their own microprocessor from individual components.

They make it easier for themselves by emulating the relatively low-powered processors found in the first personal computers.

That's a sensible step given that the microprocessors inside a contemporary PC have millions, if not billions, of transistors on board. Wiring or soldering those would take several lifetimes.

Parts list

But that takes nothing away from the complexity of building a processor from parts. Even a simple one can take months, often years, to put together.

One of the first to do a DIY processor was Bill Buzbee who made one from TTL logical chips, 74 of them in all.

Before microprocessors were invented, early computers used scores, sometimes hundreds of simple integrated circuits wired together to create a central processing unit. Such systems are known as Transistor to Transistor Logic (TTL)

"Back in the 70s when I first got involved in computers and electronics, TTL chips were what people used, so that's what I turned to," said Mr Buzbee.

Despite starting his working life as a journalist, he became a programmer and embarked on the task to firm up his knowledge of how hardware worked.

"It started out to be a very small project and it grew to something much more elaborate," he said.

Help and advice came from the many people who found his project blog, a journal he used to organise his thoughts about how to build the processor and incorporate that into a working computer.

"I have had a lot of help, most of it unsolicited, from electrical engineers," he said.

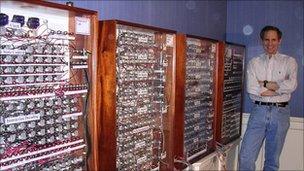

Dr Harry Porter's Relay CPU makes a fabulous racket when it is crunching numbers

Some of the parts for what would become Magic-1 were bought specifically for the job. But, true to the DIY philosophy, many others were lying around in Mr Buzbee's home.

Using store-bought and found components, the design for the machine evolved organically.

"It's not so much that I designed the computer and got the parts for that," he said. "I designed around what parts I had."

As it turned out, building the processor and its associated hardware was just part of the challenge. The novel machine needed feeding with software, including a compiler and assembler, if it was to do anything useful.

"The biggest part of the job by far was all the software," he said. "The vast majority of the time was doing that."

Was it time well spent?

"I learned a fantastic amount," he said, "I came into it with a reasonably good knowledge, but this opened up a lot of areas that I did not have much exposure to."

Mr Buzbee had the foresight to video the first working test of Magic-1 and his exclamation of "Outstanding!" as the machine does what it is supposed to sums up the project and its results.

Making machines

The trail blazed by Mr Buzbee has been followed by many others.

Computer scientist Dr Harry Porter built his 8-bit machine from relays - electronic switches that are even simpler than the transistors used in Magic-1. Despite this, the machine has all the bits you would expect to find in a smaller processor.

Relays are also a good deal bigger than transistors so the Relay Computer occupies four large wooden cabinets and makes a rhythmic clickety-clack racket when its 8-bit might is being used to crunch numbers.

Rebuilding one of these using individual components would be an impossible task

One of the most recent homebrew CPUs is the Big Mess o'Wires (BMOW) made by Steve Chamberlin from a whole lot of logic chips. Like many of the other DIY processor folks, he started small but. Over time, the design and his ambitions for it grew.

"My goal was only to tinker around with digital electronics projects of the sort I remembered fondly from university days," he said, adding that he expected that once it was built he would program and play with it via a terminal window connection to a modern PC.

"After I got the basics working, though, I kept revising my goals and adding more and more external systems," he said.

The finished BMOW has a keyboard, VGA video, audio and is programmed using Basic.

"BMOW grew into a stand-alone computer system, independent of any PC, and roughly similar in capabilities to 8-bit computers of the early 1980s," he told the BBC.

The journey from bits to finished computer taught him a huge amount about how computers work and the challenges that faced those early computer makers.

"I feel I have a much better appreciation for what it must have been like when Steve Wozniak designed the original Apple, or other homebrew systems of the day," he said.

- Published4 May 2011

- Published28 April 2011

- Published23 November 2010

- Published26 August 2010

- Published21 June 2010