Who loves the hacktivists?

- Published

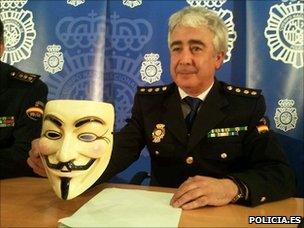

Spanish police show off an Anonymous mask after arresting three suspected members

The oft-repeated aphorism "one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter" could easily be applied to the world of computer hacking.

Just as spray-painted graffiti can represent either a mindless act or a political statement, the take-down of websites and theft of user information means different things to different people.

The subjective nature of what these shadowy troublemakers get up to is exemplified by the use of the term "hacktivist".

Anonymous and Lulz Security - two of the highest profile groups at work today - sail under this flag.

"There has always been a streak within hackerdom of ideology mixed with technology," says Peter Sommer, author of the seminal 1980s text The Hacker's Handbook.

The hacker, explains Mr Sommer, is distinct from the cyber-criminal, whose motivations are generally larceny and whose relationship with technology is akin to the housebreaker's relationship to the jemmy - it is a tool of the trade.

Hackers are interested in the mechanism of attack as much as they are in the target.

"One strong element in hacking is seeing how things work. Here is a technology, can I make it do something else?" says Mr Sommer.

That love of technological innovation, and the internet in particular, gives rise to a philosophy.

Data war

Hacktivists typically believe it is their mission to protect the net's founding principles of openness, free access and democracy.

"You have always had this strain of people who were either libertarians or getting on for socialists, who believe that computing was for the masses and want the internet opened up," says Mr Sommer.

'Coldblood', a member of the group Anonymous, tells Jane Wakefield why he views its attacks on Visa and Mastercard as defence of Wikileaks.

"A strong part of the ethic is that this makes the world more democratic - diminishing the role of the nation state."

The belief that the great internet experiment is under attack by greedy corporations and over-reaching states has sympathisers far beyond the hacker's bedroom.

Mr Sommer counts himself as one of them, although he suspects for some, the philosophy is applied retrospectively - an ex-post-facto justification for criminality.

Anonymous, which was born out of the 4chan imageboard website, has always been politically motivated, although the scale of its targets has increased over time.

In its early days, the group targeted the websites of white supremacist radio host Hal Turner and the Church of Scientology.

Following the Wikileaks State Department cables debacle, Anonymous launched denial-of-service attacks on companies that had tried to hamper Wikileaks's operations.

At that time, Anonymous member Coldblood spoke to the BBC.

"I see this as becoming a war. Not a conventional war. This is a war of data," he said.

"We are trying to keep the internet open and free for everyone, just as the internet has been and always was. But in recent months and years we have seen governments, the European Union trying to creep in and limit the freedom we have on the internet."

Just for Lulz

From the outset, Lulz Security pursued a different agenda.

On the face of it, the entire LulzSec project was a joke. The group's agenda, in as much as one exists, is posted on the front page of its website.

"We're LulzSec, a small team of lulzy individuals who feel the drabness of the cyber-community is a burden on what matters: Fun."

The message is accompanied by the theme tune to The Love Boat - a kitsch classic television series.

However, it soon became apparent, by its actions and pronouncements, Lulz had a point to make about online security.

The group hacked a database of would-be contestants on the US version of the X Factor and released the personal details online.

Hits on Sony, Nintendo and a handful of other games companies followed. Each was entered with apparent ease.

In addition LulzSec took a number of websites offline using denial-of-service attacks. The FBI, US Senate and the UK's Serious Organised Crime agency have all been targeted.

Soft targets

But LulzSec's core focus remains exposing poor security.

Although innocent web users are often caught up in the protest, the group enjoys broad support.

"I can't condone anyone breaking the law, but I do understand where they are coming from," says Peter Wood, chief executive of First Base Technologies, which tests companies' security systems.

"Because they publish not only the data they retrieve but also the methods they use, we can study those methods and see that the targets they chose have very poor security."

Mr Wood says the sheer brutality of the Lulz Security raids means companies might now choose to listen to their IT managers, whose requests for greater investment in security systems are often ignored.

Such views are not uncommon. Many security specialists say privately that they are happy LulzSec is running amok online, highlighting the need for a renewed focus on data protection.

Yet it is worth remembering, in the dissection of hacking, that the reality lies between extremes.

Mr Sommer realised this when he wrote his introduction to the Hacker's Handbook in 1985.

It reads: "It is one of the characteristics of hacking anecdotes, like those relating to espionage exploits, that almost no-one closely involved has much stake in the truth.

"Victims want to describe damage as minimal, and perpetrators like to paint themselves as heroes while carefully disguising sources and methods."

Tellingly, he adds: "Journalists who cover such stories are not always sufficiently competent to write accurately, or even to know when they are being hoodwinked."

- Published26 June 2011

- Published16 June 2011

- Published9 June 2011