The future of the silicon chip

- Published

As chips shrink, a missing atom or two might make a big difference

For more than 40 years, the processing power of the silicon chip has grown in line with a prediction made by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore in 1965.

Moore's Law states that the number of transistors that can be placed on a chip for the same cost will double roughly every two years.

Generally, that doubling has been achieved by shrinking transistors - the basic processing units of a silicon chip.

But everyone knows that, at some point, Moore's Law will halt because transistors can get no smaller.

Around the world, professors, PhD candidates and grad students are looking to nanotechnology to go far beyond the tiny dimensions in current chips.

But "heroic" techniques that work in the laboratory will not scale up to the numbers demanded by industrial chip production, according to Prof Mike Kelly from Cambridge University's Centre for Advanced Photonics and Electronics.

"They can do it in the labs and get one off results," he said, "but there's another whole side to this as well."

The problem emerges, he said, because tiny components are made up of such a small number of atoms. The number of atoms in a structure, such as a gate in a transistor, determine its electrical properties.

Prof Kelly's work suggests that if only one or two atoms are missing it will have a disproportionately large effect on that component's reliability.

For silicon chips, making that compromise is not an option. Typically, said Prof Kelly, chip makers strive for what is known as six sigma reliability - with a chip this means it returns the expected answer 99.99966% of the time.

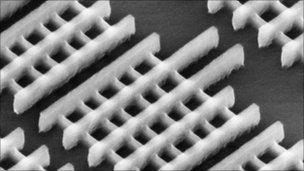

The latest chips from Intel will be built with components only 22 nanometres (nm) across. By comparison, a human hair is about 60,000 nm wide. Intel and other chip makes have plans to go to 14nm and then 11nm.

"The big question," said Prof Kelly "is at what stage does one or two atoms make a difference?"

Engineering history has lessons for chip makers keen to keep Moore's Law on track, said Prof Kelly.

Marine engineering hit a problem during World War II, he said, when established techniques for manufacturing propellers were pushed too far.

The history of engineering may have lessons for chip makers, warns nanotech expert

Those techniques had largely involved simply finding ways to make propellers bigger and bigger. Eventually, the result was propellers that turned out to be far less efficient because the shafts to turn them sagged under their own weight.

Prof Kelly's fear is that unless chip makers significantly change current top-down manufacturing techniques they could be headed for a similar crunch moment.

Typically, making a chip involves creating a stencil of the circuit, etching it onto a silicon wafer and putting the components on it layer by layer.

"Beyond 14nm that is going to get very, very hard," said Prof Kelly.

Mike Mayberry, director of components research at Intel, agreed with Prof Kelly that top down manufacturing techniques have a technical limit.

"We need to do something different," he said. "We cannot keep driving down that road without turning the wheel."

Changing the way chips are made is the only option, according to Mr Mayberry.

"We are mixing top-down methods with bottom-up methods and we are going to be able to build things we could not do before," he said.

One method Intel and others have adopted is the laying down of several one-atom thick layers of a material that helps make the individual components more reliable.

Professor Sir Mark Welland, head of the Cambridge University Nanoscience Centre, said such techniques had their uses but did not remove all the uncertainty.

"In order to get a good structure they would have to seed the surface in some way in order to grow from the bottom up," he said. "Then you have the same issue, how well can you lay down a pattern?"

The components in Intel's latest chips are about 22 nanometres across

What should be remembered, said Prof Welland, was that Moore's Law was an economic law and has more to do with what it is possible to do for the same cost.

Until now, the desire to drive down price has led to transistors being made smaller and packed in ever more tightly. But there is nothing in Moore's Law, said Prof Welland, which says that was the only way to keep it going.

Mr Mayberry at Intel said his company was investigating other ways, apart from shrinking components, to make processors more powerful and useful. Internal architectures could be changed to help more data flow at any one time, he said. Sensors and wireless transmitters could be more closely integrated onto the chip.

"There are going to be incremental advances in all parts of the architecture," he explained.

"It can be about making them more useful, consume less power or take up less space."

In the mean time, drawing up a road map to keep Moore's Law rolling on was tricky, said Mr Mayberry.

"We look down the road and it's foggy. The nearby stuff is clear and we can see that the big stuff is there but we cannot see the details.

"The horizon is about 10 years away."

- Published4 May 2011

- Published29 October 2010

- Published4 May 2011

- Published25 May 2010