Look out, there are monsters about

- Published

Moshi Monsters does what it says on the tin - it contains monsters

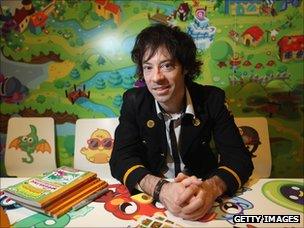

Four floors up in the achingly cool Tea Building in the heart of London's Shoreditch are the remarkably welcoming offices of Mind Candy.

In one area of the open-plan room is a smoothie bar. In another, a play zone littered with bean bags and toys - lots of toys.

Near the far window, past a long wooden dining table and a set of bouncy leather sofas, sits Michael Acton Smith, one of Britain's leading entrepreneurs.

"We've done deals with trading card companies, toys, magazines," he starts.

"I really want to do a live tour, I really want to release a music album. I want to do a film, a cartoon."

You get the impression, given the chance, this brainstorm could go on for several hours.

Words flow easily for Smith as he talks about his huge success story: a social network aimed at seven to 12-year-olds called Moshi Monsters which he founded in 2007.

"I was going to call the site Puzzle Monsters. Kids didn't like that idea," Smith remembers.

The kids may have scoffed at the name, but they certainly didn't at the concept.

Four years on, it is estimated - by the company - that about one in three UK children aged between seven and 11 look after a Moshi Monster. Across the world, 50 million children have signed up, and have played the site's mini games millions of times.

Moshi Music, the record label featuring the ever crowd-pleasing Lady Goo Goo, released its first single this month and has its eyes firmly set on pulling a Bob the Builder and getting to number one.

Its most remarkable achievement of all? Many of the site's users - or rather, their parents - pay a £5 a month subscription charge. Adults are more than happy, Smith says, to pay a fee to give their kids access to a monitored environment online.

'Commercially disastrous'

Moshi Monsters began life when Smith pondered how best to use the last remaining capital from a struggling social-gaming product named Perplex City.

While it was "creatively amazing, commercially disastrous", Smith says it taught him enough to kick-start his next idea.

"Kids loved technology and they loved the web. I felt this could be the next amazing arena.

"With our last little bit of cash left I said to the board, 'I don't think this is working, but I've got this other idea...'"

Mind Candy founder Michael Acton Smith is building an empire, including books, toys and a magazine.

What excited Smith was the chance to create a single website which could be experienced in different ways by various different ages and sexes - unlike, say, a television show.

"When you create a TV show, it's almost like a 'one size fits all'. Thomas the Tank Engine is for pre-school kids, and so is Dora the Explorer. But when you create a web property, kids can experience it in different ways."

The site allows children to communicate with each other's monsters, while also earning "rocks" - the in-game currency - by playing various, mostly educational, games.

"If you can sprinkle some game mechanics into learning - rewards, playing against the clock - it can be hugely successful, and it is.

"Hundreds and hundreds of millions of puzzle games have been played at Moshi. The better they do, the more 'rocks' they earn and they can go shopping and buy cool stuff.

"It's subtle - we call it stealth learning. It's a tricky balance, but I think we've struck it pretty well."

Smith's game plan was to then carefully create a wider brand outside of the internet, with a range of products tied in to the characters children already cherished.

"We don't want to alienate parents, but we are a for-profit business, and to run a big staff here requires us to make profits and so forth.

"It's a careful balance. We very carefully vet every product that is released. We try where we can to weave educational elements into them."

It's a business model beautifully demonstrated, of course, by the legendary Walt Disney Company.

"They are the masters at creating characters and then building franchises around them in a very smart way that isn't exploitative, but is a wonderful way for people that love and care for those characters and stories to experience that brand in different ways."

Far from just being a company to aspire to, Moshi now counts Disney as just one of its many rivals. In 2006, the American giant bought another massively successful children's social site, Club Penguin.

Despite facing the big guns, Smith says he is unphased and has a clear vision his company is heading.

"It's really exciting to be building what I think is hopefully going to be the biggest kids entertainment brand of the digital age."

Training wheels

In doing so, Smith and Mind Candy hold a unique and important responsibility.

Disney's Club Penguin is one of Moshi Monsters' main rivals.

"Moshi is almost like a social network with training wheels on," he suggests.

"Far better that at least there's a little buffer like Moshi rather than them just getting dropped straight into Facebook.

"Parents know how much their kids love the web - but they'd much rather that takes place in a walled garden, a site deliberately designed for under-13 year olds."

"Deliberately" is Smith's buzz word here - the entrepreneur has concerns over Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg's public brainstorming earlier this year over opening up the world's biggest social network to younger children.

"I think it depends how they are looked after," Smith says.

"That's a big question. I think there'd be a fair bit of resistance to it.

"It would need to be a different Facebook to the open web. For instance, at Moshi, there's no private messaging. Everything is out in the open.

"We spend a huge amount of time keeping the site as safe as possible. So if Facebook did it, they'd need to ensure there's a lot of checks and balances to make sure it's safe."

Understandably, safety plays a massive part of Moshi's day-to-day operation.

The site adheres - like all online communities which cater for under 13s - to the Children Online Protection Act, legislation which covers, among other things, the collection of data from children.

Smith says he appreciates the government's fairly stand-offish approach with regards to regulation, but admits it is the responsibility of sites like Moshi to make sure this currently mutual trust isn't broken.

"So far it's been very self-regulating.

"The government is smart and they recognise it doesn't make sense for them to try and regulate and set hard and fast rules for the online space - because things are moving quite quickly. It's quite a light touch that they have.

"If any company did step out of line, there would obviously be a huge backlash. We've not only got to keep our kids safe and happy, but we also have to ensure that parents feel the site is safe."

World domination

In terms of sheer numbers, Moshi's biggest audience is in the United States. But it's outside of the English speaking world where Mind Candy's next potential audience awaits.

Smith says he has already set the wheels in motion to have the site translated into, among others, Spanish, Chinese and Russian.

That said, non-English speakers already frequent the site.

"What we've noticed is parents in countries in the Far East have been pushing their kids to sign up to Moshi to learn English and get pen friends in England and America.

"We'll actively encourage kids to talk to each other in their different languages."

Beyond that, Smith is unsure where his empire will try to conquer next. Or perhaps he is just keeping it close to his chest.

What he does openly predict is that the abilities of children to use the web will grow ever more sophisticated.

"Kids are getting savvier online," he muses.

"This generation of kids is pretty much the first where their parents just about grew up with the web - so the parents are incredibly comfortable with the web, and video games, and not scared about it as my parents and parents of the previous generation were.

"This is the world that these kids are growing up in - they will find their jobs using LinkedIn, they'll make many of their connections on Facebook.

"It's not right or wrong, it's just the way of the world."

- Published22 September 2011

- Published22 September 2011