This is the future calling

- Published

Sometimes it can be hard to get a strong mobile signal

When science fiction writer William Gibson observed that the future is already here, it is just not very evenly distributed, he could have been thinking of mobile networks.

Those networks are a patchwork of second and third generation mobile technologies which has become a problem as we do more with our phones than just talk and text.

It means that web access is blazing fast in one location, absent close by and limping along at a snail's pace around the corner.

But, say many mobile operators, this will be a distant memory when fourth generation (4G) mobile technology is put in place.

Big changes

The problem with this claim is that the 4G technology operators are blowing the trumpet for, known as LTE (Long Term Evolution), is not officially 4G.

The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) has the job of deciding which G is which. Under its definition, LTE is 3.9G.

The ITU's standard for 4G technology demands that it be capable of pushing data around at a rate of 1 gigabit per second. LTE is designed to handle a mere 100 megabits per second.

Despite this, LTE will bring in big changes for mobile networks, says Dan Warren, senior director of technology at the GSMA, the industry association for mobile networks.

"The original GSM networks were designed primarily with voice optimisation in mind," he said. "That involved low delay but relatively low bandwidth over an air interface that in the 80s was quite unreliable."

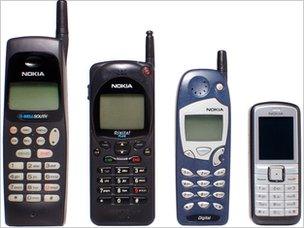

Essentially those early networks were all about talking on the phone with a tiny bit of texting involved. Bracketed around this was lots of error correction technology to ensure your call did not drop out.

But mobile users are no longer happy to do mainly talking and a bit of texting.

"There's a recognition in the industry as a whole that data and access to the internet are of vital importance," said Mr Warren.

This is where LTE comes in.

"When you get to LTE you do not have voice delivered in the traditional way any more," he said. "In LTE everything is treated as data and it is all handled by the same core network."

This means we should be able to get more out of our smartphones, tablets and e-readers as broadband speeds will be generally faster.

Power play

But for all its advances, LTE does have a downside in that it makes very heavy use of the spectrum allocated to it. And some feel that LTE and its successor technologies stick too closely to what has come before.

As phones shrink, the legacy of the network stays with them.

That technology legacy is making itself increasingly evident, claims Rajarshi Sanyal, a telecoms researcher from Brussels.

Working with Prof Ernestina Cianca from the University of Rome and Prof Ramjee Prasad from Aalborg University, he is looking at an alternative way to build a mobile network, one simpler than what we have now but still able to support high data rates.

Their contention is that mobile networks are getting too complicated to manage effectively. That, they say, is not just a problem for operators.

It has a knock-on effect to handsets too.

"Not only are mobile networks today complex but they need active elements at every nook of the network," said Mr Sanyal. That means each handset has to devote a chunk of its processing and battery power to maintaining contact with the network.

As the number of mobile users increases and the cell sizes shrink, this continuous interaction between the handset and the network implies a substantial overhead on the network.

A network in which that burden is lessened would mean phones spend fewer processing cycles and battery power checking in. The researchers have come up with a design for just such a system and are setting up a demonstration to show how their suggested admin-lite network might work.

"With the same processor you leave more room for catering to the next generation of network driven applications," said Mr Sanyal.

The idea has some merit, said Mr Warren.

"If you were to take a purist view and scrap everything we have today and replace it, then absolutely you could do something a lot simpler," he said.

However, he added, the practicalities of building a network mean those simple choices cannot be made.

Money talks

But even as networks get better at handling data and the bandwidth speeds rise, operators could face another problem - how to persuade people to splash out and buy a new LTE handset.

Mobile networks are changing as we do much more than just talk and walk

"Going to go from eight megabits per second to 20 Mbps you will see the difference, but it's not the same impact as if you went from dial-up to broadband," said Carolina Milanesi, an analyst at market research firm Gartner who specialises in mobile devices.

Selling that first uplift was easier, she said, because the difference was so stark. What also fed into that initial demand for 3G phones was the fact that the handsets that worked on those networks were among the first to have cameras. Together the two drove demand and got people onto those faster networks.

Such a feat is going to be harder to repeat this time around, she said, because all those features we are used to on a smartphone will already be present. And the slight uptick in browsing speed or how quickly applications load may not be enough to get people to fork out for a new handset.

"You can see that cost is an issue if you look at the deployment of 4G," said Ms Milanesi. "It's an issue because operators are going a bit more cautiously simply because they spent so much on 3G licences."

The UK's 4G auction was due to take place in early 2012 but has been delayed to later the same year as regulator Ofcom gathers information from operators about how it should be run.

Operators spent billions to buy a 3G licence and will have just one question about any cash they spend, said Ms Milanesi.

"This time," she said, "they will be asking how do we get some of that money back?"

- Published24 August 2011

- Published31 August 2011

- Published25 May 2011

- Published22 March 2011

- Published2 December 2010