How to breathe new life into the PC

- Published

PCs need to be more like TVs and start working as soon as they are switched on

For a long time personal computers have stood apart from many of the other electronic devices, such as TVs, cars and telephones that we use.

Never do we have to wait for the car to boot up before we can get in and drive, nor do we have to wait for the TV to finish a power-on-self-test before we can veg out in front of it.

Instead, these devices are ready to do our bidding the moment we sit behind the wheel or rescue the remote from behind the cushion.

By contrast, our home PCs are downright surly when woken and take their own sweet time to get ready to accept our mouse clicks.

But that reluctance may be about to change.

So said Justin Rattner who as Intel's chief technology officer should be in a position to know.

"We are at a very interesting point in terms of the products we can make," he said, during a rare visit to the UK. "Anything we can imagine we can build, we are no longer really limited by the technology."

Allied to that, he said, was an increasing realisation that the experience that people have with their computers has become more important than the underlying chips and peripherals

"Users have come to understand that their expectations have shifted dramatically," he said. "There is less and less willingness to accept products that do not create a very favourable impression and a very good experience."

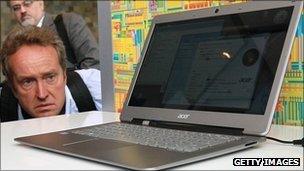

Ultrabooks are supposed to be thin, have a long battery life and cost less than £650

It was this, said Mr Rattner, which led Intel to define what have become to be known as ultrabooks. These are laptops and other portable computers that Intel and its partners hope will overturn our expectations about what PCs do.

The specifications for the ultrabook say it should be less than 21mm thick (and preferably much less), start up instantly, have a battery life of at least five hours and cost less than $1,000 (£650).

Intel first started talking about ultrabooks in mid-2011 and the first laptops and devices that meet the specification are starting to appear.

"The ultrabook is, in some senses, an attempt to bring the PC into an age of computing that's more experience driven," said Mr Rattner. "We cannot just sit on our thumbs and say a PC is what a PC is what a PC is."

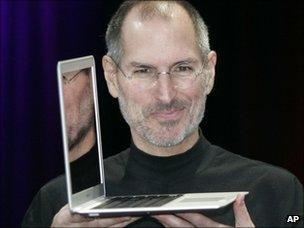

The ultrabook is also, in some senses, an answer to what Apple has done with the MacBook Air and its famous focus on usability.

Intel called on social anthropologists, ethnographers and human factors experts who all gave their views on how ultrabooks should work to satisfy the expectations of the modern computer user.

One way to aid that is by giving ultrabooks the ability to receive email, IMs and the like while dormant. That means, said Mr Rattner, those messages will be instantly available when the machine is powered up. There will be more waiting while it polls the server to see if anyone has been in touch.

The Ultrabook tries to bring some features of the Macbook Air to Windows PCs.

"The PC has continuously demonstrated its ability to change with the times," said Mr Rattner. "It's an extremely adaptable animal and is undergoing some fairly dramatic changes."

Such changes are going to be essential if the PC is to expand beyond its comfort zone of the back bedroom or on the lap of the couch surfer.

It has to make these changes if it is to be useful when watching TV or driving a car at speed. A spinning hourglass is not going to keep the kids happy in the back of the car if they were expecting to be playing games against their mates as they are driven down the autobahn.

"It just has to be there," said Mr Rattner. "It has to be connected."

Increasingly, he said, PCs will have to come to resemble those devices and jump to do our bidding when we are ready.

"The ultrabook is the first explicit evidence that the PC is not about to curl up and die," he said. "But in fact it's going to evolve and take on many of those device-like properties."

- Published28 September 2011

- Published10 September 2012

- Published11 August 2011

- Published28 June 2011

- Published7 June 2011