Viewpoint: How hackers are caught out by law enforcers

- Published

The internet has gained a reputation as somewhere you can say and do anything with impunity, primarily because it is easy to disguise your identity.

This feature has proved particularly helpful to hackers, many of whom have developed a feeling of invulnerability, and even boast that they will never be caught.

However, the arrests of members of the hacker group Lulzsec this week, and some other recent but less high-profile arrests, show that the authorities are not quite as impotent as many would have you believe.

Increasingly, hackers' boasts are followed shortly afterwards by a surprise visit from the local police. So, how do these investigators catch these new-age criminals?

Internet addresses

To start, one needs to take a step back and understand how it is that people can obscure their identity on the internet.

Most people rightly assume that if you connect to the internet you are given a unique address (your IP address), and, not unreasonably, people assume this could be used to trace back any activity emanating from that address to an individual.

And sure enough, given an IP address, anyone can look up the details of where that IP address originates: there are many publicly available services on the internet that anyone can use. However, it is not that simple, and certainly not quick, for several reasons.

Firstly, many years ago the number of devices on the internet requesting an IP address exceeded the number of possible addresses.

Consequently, when any of us asks our internet service provider (ISP) to connect us, whilst we are given an IP address it is only leased to us.

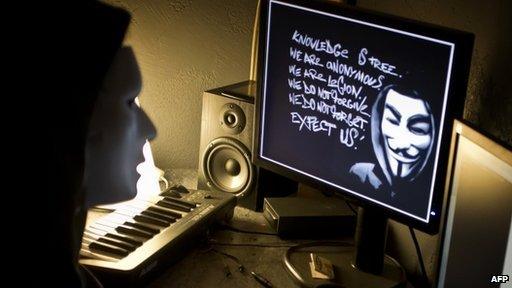

Hackers sometimes use proxy services to avoid leaving digital fingerprints behind

These IP addresses typically expire quite quickly at which point it is renewed if you continue to want access or it is given to someone else if we have disconnected.

Your next connection provides you with a completely different address. Look up an address and it will usually only tell you who the ISP is, not who held the lease at a specific time.

So, even if an investigator saw illegal activity emanating from a specific address, it is unlikely that they would easily be able to track down the user using publicly available data.

The authorities would have to go to the service provider and ask for their records to show exactly who was using that address at the time of the illegal activity.

As law enforcement agencies have to obey the law this usually requires a warrant issued by a judge, all of which requires the investigators to show that illegal activity was under way and that it appeared to be coming from a particular ISP.

They cannot simply go on a fishing trip.

Nonetheless, investigators have become more and more proficient at this process, so hackers (at least the ones that have not been caught yet) have long since ceased to rely upon this although most rightly assume that it will slow down the authorities and make them less agile than the hackers.

Co-ordination complications

Secondly, all of the above assumes that the service providers keep records of who had a particular lease.

In the UK they do, but not every country is quite that diligent, and certainly not necessarily to the level of detail required to physically locate a miscreant.

Even in the UK, the volume of data is enormous and it cannot be kept indefinitely. The UK is introducing legislation to oblige ISPs to keep records but even that does not require those records to be kept for ever.

Thirdly, being a global network, the internet comes under multiple jurisdictions.

If it takes time for an investigator to be granted a warrant in his or her own country, imagine the difficulty of doing so in another country.

So it's not surprising then that most hackers tend to attack sites outside their own country. Moreover, hackers co-operate across jurisdictions adding further complexity to an already tricky situation.

However, this week has highlighted the role of cross-border co-operation with arrests being made in UK, Ireland and the US.

Increasingly, international bodies such as Interpol and Europol are taking a lead in enabling collaboration between the agencies in several countries simultaneously.

Proxy defence

So, assuming you can navigate all of the above complexities, you can track back an internet address, and catch your perpetrator? Well, not necessarily.

As ever the technology runs well ahead of the legislative and judicial systems. Today there are a couple more tricks that allow you to cover your tracks on the net.

The most widely used is called the proxy.

Alleged members of Lulzsec, Antisec and the wider Anonymous group have been arrested over recent weeks

Using a proxy server anyone can bounce their activity off a system that is either in a far distant country, or keeps no records of where the activity originated, or worse still, both.

Proxies gained popularity among those doing illegal downloads - so that they could not be traced.

Proxy services are widely available, often for free. They have developed a very important role in allowing people in hostile regimes to have their say anonymously.

But, of course, they can also be misused for illegal purposes. And so besides those undertaking illegal activities such as copyright theft, the hackers have been quick to realise their potential.

But all is not lost even at this stage.

The investigators can do what they call "traffic analysis" which relies upon using a combination of records from several ISPs, and in this way cut the proxy service provider out of the loop.

Not surprisingly this takes even longer and the added complexity inevitably means less reliable results when trying to secure a prosecution.

However, one of the big advantages that the authorities have is that they are patient: they don't boast about what they are doing, quite the opposite, and they are prepared to grind through the detail to get their man or woman.

The dark web

Of course, the hackers know all of this and so the arms race has continued. Most hackers now, in addition to relying on all of the above, use what is called "onion routing".

Perversely it began as research to protect US Naval Communications, but ever since the technique was published at the Information Hiding Workshop in 1996, people have seen it as a general means of maintaining anonymity on the internet.

The most widely used is called Tor. Again it has many valid uses, but the hackers are delighted to use it as well.

It is projects such as Tor that represent the front line for investigators today.

Currently they have very little answer to onion routing, and when combined with the other complexities I've outlined the law enforcers face a significant challenge.

But do not write them off just yet.

Global service providers are working with researchers on projects such as BT's Saturn which was originally developed to identify threats to the UK's critical national infrastructure. But in the past year it has been used for some very interesting purposes.

The example shown here is snapshot showing sources (red) of intrusion attempts and destination (green) of those intrusions. The size of the circle indicates the number of events.

Watch that space for more developments.

Dominos

Meanwhile, enter good old-fashioned police work.

The principle is simple: everyone makes mistakes. Take the case of the hacker known as Sabu.

He regularly talked to others using internet relay chat (IRC). Reading messages allegedly from Sabu, apparently leaked by his fellow disgruntled hackers, he was quite boastful about what he had attacked, his invulnerability and his technical prowess.

He therefore set himself up as an obvious target for surveillance.

It appears that just once, Sabu logged into his IRC chat service without using Tor. His IP address was revealed and the FBI traced him. That led to charges against other suspected hackers.

You will see more of this tactic: decapitate by arresting the big fish and then attempt to sweep up the smaller fry based on what you learn.

In short, a lack of news does not mean that the hackers have it all their own way, despite what they might like you to think.

Whilst the arms race continues in cyberspace, what has become clear is that what works is the combination of the old and the new.

Prof Alan Woodward is a visiting professor at the University of Surrey's department of computing.

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published22 November 2011

- Published8 March 2012