The hacker way: Will Facebook change after flotation?

- Published

How much, or how little will Facebook change after flotation?

"How do we make this thing not go down?"

That was Dustin Moskovitz's overriding concern the first 12 months into creating "thefacebook" at Harvard with college chum Mark Zuckerberg.

The dorm-room project they had embarked on as undergrads was growing like a weed and was proving just as unwieldy.

Mr Moskovitz had only enrolled in an introductory computer science class the semester before starting an early version of Facebook.

At 19, he emerged as the first technology lead of the scrappy project that morphed into a real start-up.

"We made a lot of mistakes," acknowledged Mr Moskovitz during a recent sold-out talk in San Francisco.

It's a refrain heard throughout Facebook's eight-year history.

Building things. Then breaking them. Over and over again. It's what Mr Zuckerberg and his team call "the hacker way".

To their way of thinking, "If you're not breaking things, you're probably not moving fast enough."

It's an approach engrained in the company's uncommon culture and management style.

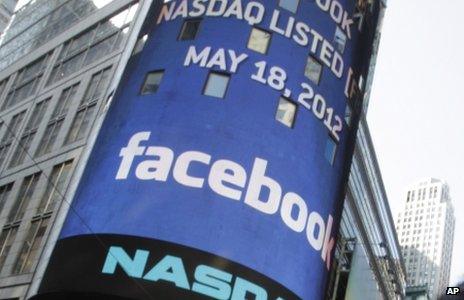

Going public

Now the start-up that never intended to be a company has gone public.

Everyone is watching to see if the hoodie-wearing "boy CEO," as he's been called, can parlay his mojo into a lasting and profitable, publicly-traded global enterprise.

Mr Zuckerberg's deepest concern seems to be how to keep "the hacker way" alive, David Kirkpatrick, author of "The Facebook Effect," a book that gave an inside account into how the social network connected the entire world, told the BBC.

In 2007, Mr Zuckerberg said Facebook was not looking for an exit

"That's what Mark is most afraid of - that Wall Street's oversight and scrutiny is going to slow the company down," he said.

No exit?

It seems that for Mr Zuckerberg, money alone was never a draw.

The mission has always been "to make the world more open and connected".

Since writing that first line of code, Mr Zuckerberg's focus has remained on the platform and product strategy.

That was underscored when he rebuffed Yahoo's $1bn takeover offer.

It wasn't a universally popular decision inside Facebook, but Mr Zuckerberg stayed true to his vision.

"As a company, we're very focused on what we're building and not as focused on the exit," Mr Zuckerberg said in a 2007 interview with <link> <caption> TIME magazine</caption> <url href="http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1644040,00.html" platform="highweb"/> </link>

"We're not really looking to sell the company. We're not looking to IPO anytime soon. It's just not the core focus of the company."

Flotation impact

Silicon Valley insiders and those close to the company doubt the flotation will change Facebook much.

How little might it have an impact on Facebook - that's the more interesting query, according to Mr Kirkpatrick.

"Even after it's public, I don't think Facebook is going to act that concertedly differently as a company," he said.

"Mark Zuckerberg will not get on the [quarterly] calls, but I think he will continue to run it in the way that he does, which is with absolute authority and quite extreme paranoia, in the sense that he will make rapid decisions in order to avoid Facebook being marginalized or hurt by sudden developments that are inevitable in technology."

This will be possible because Mr Zuckerberg retains the ownership of 57% of the voting power, Mr Kirkpatrick noted.

"Because Mark is going to have total and complete control, despite [Facebook] being public, it doesn't have to change that much in the way it's run.

Instagram acquisition may help Facebook develop its mobile strategy

"What's more, he doesn't have to consult with shareholders."

The underlying reason Mr Zuckerberg is in this rarefied position is because many of his friends, co-founders, and big investors have turned their voting rights over to him, Mr Kirkpatrick explained.

People like Sean Parker, Facebook's first president, and Dustin Moskovitz, who own considerable amounts of voting power of the company, have decided it's best for the company - because then, "Wall Street couldn't screw them over too badly," said Mr Kirkpatrick.

Mobile and e-commerce

Today, more than half of Facebook's users connect via mobile devices.

Yet despite its technical prowess and resources, the company has been critically savaged for its mobile apps.

In the future, "mobile will absolutely be a number one priority," said Bill Gurley of Benchmark Capital, the leading institutional investor in Instagram, the popular photo-sharing app that Facebook recently bought for $1bn.

It's a "brilliant acquisition," agreed Stewart Alsop, an investor in Silicon Valley, adding that Instagram could help Facebook to develop its mobile strategy.

"The biggest threat Facebook faces is mobile…their mobile stuff is terrible," said Mr Alsop.

Facebook has spawned a chain of other companies on its platform like Zynga, BranchOut, Spotify and Payvment.

This year could be the breakout one for shopping on Facebook, Christian Taylor, founder and chief executive of Payvment, told the BBC.

This e-commerce platform helps small and medium-sized businesses add shopping capabilities to their Facebook pages.

Rick Marini, chief executive of BranchOut, says that his e-commerce app is thriving on Facebook

Payvment, with a 25-person team, sees one and a half million people shopping at its stores every month - and boasts it handles 80% of the commerce transacted on Facebook.

BranchOut, another app that resides solely on Facebook, for professional connections and job hunting, is also thriving within Mr Zuckerberg's ecosystem.

Growing faster than LinkedIn with three new users per second, BranchOut saw its user base grow from 400,000 last December to 13 million four months later, said its founder Rick Marini.

Team work

Software development is collaborative.

At Facebook's swanky new headquarters in Menlo Park, California, engineers feel at home.

Spread over a total of 79 acres, the campus is devoted to their every whim: free food, small team-based projects, frequent hackathons, open bars stocked with alcohol.

And their founder is intent on maintaining an environment where engineers can thrive and come up with ideas.

That's "the hacker way".

- Published18 May 2012

- Published18 May 2012

- Published18 May 2012

- Published17 May 2012

- Published17 May 2012

- Published18 May 2012