The future of Google Search: Thinking outside the box

- Published

Amit Singhal, head of search at Google, talks to Leo Kelion at the company's London headquarters

The world's most popular search engine is trying to become more intelligent.

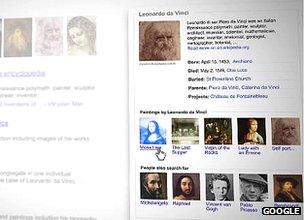

Last month Google announced <link> <caption>the introduction of the Knowledge Graph</caption> <url href="http://insidesearch.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/introducing-knowledge-graph-things-not.html" platform="highweb"/> </link> in the US - an effort to improve its results by teaching its servers to understand what the words typed into its search boxes mean, and how they relate to other concepts.

It marks a big bet by the firm's head of search, Amit Singhal, who discussed the move with the BBC.

<bold>In the past search engines haven't really known what words mean, how are you trying to change that with artificial intelligence? </bold>

We had already done a lot of wizardry to give you relevant text, images and video in one simple interface, but computers still didn't understand that the Taj Mahal is a beautiful monument. Or it can be a Grammy-winning artist. Or it can even be casino in Atlantic City, New Jersey. And depending on if you are feeling hungry, it could also be a neighbourhood restaurant.

Mr Singhal revamped Google's search algorithm in 2001 and was put in charge of the feature

To human beings that's just intuitive.

To computers it's not, because of the following fundamental fact: computers are really good at representing strings of characters. They use Ascii and various other nomenclature to represent sequences of words and numbers, whereas human beings live in a world of things, not strings.

What we did two years back was we acquired a company called Freebase that had found a novel way to represent things in computer memory.

It was such an exciting opportunity because we can finally realise our dreams of moving search from being about strings to being about things.

<bold> But that company only had a fraction of the number of objects and concepts categorised that you would need to make this work. </bold>

Absolutely. Freebase had 12 million entities or things in it. And we invested heavily in it over the last two years.

It now has knowledge of more than 200 million things. Not only that, it has interconnectivity between them.

For example, David Cameron is an entity, so is UK, and there is a relationship there of prime minister, and we represent that as well. It gives you what we call a Knowledge Graph.

<bold> Does this Knowledge Graph let the computer understand what David Cameron is in the same way we do, or is it just a new, more complex algorithm? </bold>

The truth is even we don't know how we as human beings understand things. We don't understand how our brain represents objects.

To a computer, understanding means when you ask it something, it can tell you a lot more about that thing.

For example it will be able to tell you for Taj Mahal that it's a monument, where it is, what you should know about it if you are interested in it, and not just a bunch of links.

So I find that is a step closer to understanding than the current search systems.

Is it representing things in a computer memory like a human does in our brains? I don't think we understand how we represent things, but the system will feel closer to our human understanding of the world.

<bold> The other big theme in search is personalisation. How do you think this will develop? </bold>

People conflate two things, context and personalisation, into this big lump called "personalisation".

Context is fundamental to running search: what language you speak and where you are right now.

The Knowledge Graph powers a side-panel providing a new way to explore a topic

So when you type the query "pizza", we give you results in London, near you, in English and not Italian results from Rome - which some would argue is the most relevant pizza on this Earth.

One of the objectives we have in the search team is to give the most locally relevant results, globally - and that's context.

The other kind of personalisation is that when I type in "Lords", I get the cricket ground and not the Dungeons and Dragons game - which most other people in America would want - because I was raised with a healthy diet of cricket.

That's personalisation which is based on you as a human being and not as a collective of citizens of London or so on. And the truth is context is more powerful than personalisation in average search usage.

In my view we shouldn't go overboard with personalisation in search because serendipity is really valuable.

We have explicit algorithms built into Google search so that personalisation does not take over your page.

You need as a user to get all points of view. I don't want anyone to only get just one point of view. So in my view it will get more relevant, but personalisation will not take over your search page.

On top of that, we will keep a control there where you can see what the page would have looked like if you turn off personalisation - but not context, because turning off context is really damaging to your results. <bold/>

<bold> At the moment people do most of their Google searches by typing into your search box. But we saw from your </bold> <link> <caption>Project Glass video demo</caption> <url href="https://plus.google.com/111626127367496192147/posts" platform="highweb"/> </link> <bold>examples of results being pushed to a user based on their situation rather than the user having to pull them with a manual search. Will we increasingly leave your box behind? </bold>

Google co-founder Sergey Brin has worn a prototype of the augmented-reality glasses in public

From our perspective you have to make life simple, and a baby step in that direction is Google autocomplete.

You type "w" - it computes that you may want "weather" because that's what most people look for when they type "w", and using Google Instant you can actually see the weather forecast without having to finish typing the query.

So what we have done is not left the box behind, but made it so that you don't have to type the whole query.

Now you can imagine there are some contextual cues where you don't even have type the first letter to fill out what most people in similar contexts do.

So for example, if someone is standing in front of Buckingham Palace and most people who stand there query "Trafalgar Square", then potentially that would be a suggestion that could happen without even going to the box.

These are all experimental research problems that we clearly think about all the time, and have to find ways to provide value to the user.

Unless we can find a product that provides value to the user, these will remain research projects.

<bold>But is your instinct that in a decade's time, much of our search activities will be done without the user having to manually initiate it? </bold>

That's a dream that may happen in 10 years but I can't predict that far out.

We live in the internet age - and 10 years is like 100 years in real life here.

But I do believe that your context is very important, and Google should be someone by your side who can help you.

I often talk about the fact that on my Google Calendar I have gaps that signal I'm free at that time.

The Project Glass demo showed a weather forecast search prompted by the user looking out of a window

And if I have a to-do list which can be knocked down, I wouldn't mind a reminder saying: "Your to-do list says call your son, you have an hour free."

That has to be unobtrusive and to the side and low key, and it has to be done with full transparency and control. <bold/>

<bold> What else does the future of search hold?</bold>

<bold/> What excites me tremendously these days is the connectivity and the mobility that the future world will have, which we are already seeing emerge through smartphones.

I have the power of thousands of computers in my pocket - because when I type a query [into a handset] it really takes thousands of computers to answer that query.

So we are sitting at this wonderful junction where various technologies are ripening: mobile technologies, networks, speech recognition, speech interfaces, wearable computing.

I really feel that these things put together will give us products five years from now that will change how you interact with computers.

The future will be very exciting once you have a wearable computing device. It kind of changes how you experience things.

- Published1 June 2012

- Published21 May 2012

- Published4 April 2012

- Published4 November 2011