Viewpoint: What 4G means for you and your phone

- Published

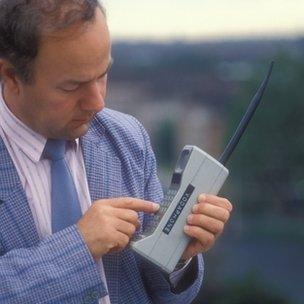

The first "G" brought the bulky brick mobile phone into being

Every 12 years or so there's a new generation ("G") of mobile phone technology.

1G gave us the analogue phone bricks, 2G saw digital phones which shrunk to the size of a business card and 3G enabled phones to become smart and use data.

4G is the next step: it makes the phone a device which communicates the same way as your desktop and provides the same or even higher data rates.

At least that's the official story. In reality once it was realised that with more than five billion mobile phones in the world all sorts of competitive pressures built up and things started to get messy.

Firstly there was the fight between competing standards: WiMax and LTE (Long Term Evolution). WiMax never really stood a chance because LTE had the same standards setting machinery which set up the previous Generations, and mobile operators just needed to upgrade rather than replace their networks.

The game was over when Apple said it was going with LTE for the new iPad.

Then there was a rush to get something - anything - up and running so as to gain market share. So whilst the "official" definition of 4G talks about one gigabit per second (Gbps) speeds, the marketing departments of mobile operators call 4G anything over 30Mbps or so.

These kinds of speeds are actually part of 3G, but this is not the first time that hype has triumphed over reality. But then it's easier to announce you have 4G if you've moved the goal posts.

Bitter pill

Finally there's the thorny issue of radio spectrum. This is the real issue behind all sorts of problem of compatibility and delays (especially in the UK).

One of the amazing things about mobile phones in the past is that they almost all worked on the same frequencies - as agreed by the World Administrative Radio Conference which meets every few years.

And because Europe took the lead on mobile phones it didn't matter that the US had different ideas - eventually commercial pressure compelled them to implement compatible systems.

But today it's different. There are smartphones and tablets, and these are dominated by the US. The US has different frequencies available for 4G - so your 4G iPad can only work with 3G in Europe. But that's not a long term problem - you can build devices which work at different frequencies.

Slipping back

The UK is falling behind places like India which already have 4G services

There's another issue which is a bigger concern. Places like the UK which were leaders in the Nineties and Noughties found themselves with a bunch of allocations and interests which have been very hard to shift.

During and after the auctions in 2001 mobile operators invested a great deal and want a return - something that has not been so easy in a very competitive market.

The problem is radio spectrum is like your worst holiday swimming pool nightmare: a lot of the space is taken up by towels and every time the attendant tries to free up a sun lounger or change the terms of use he or she finds themselves at the wrong end of the threat of a legal action - especially as some people paid a lot for their place in the sun. The attendant - in the shape of Ofcom, the regulator - is forced to tread very cautiously and slowly.

This is not what the economists predicted when they painted a bright picture of markets trading spectrum and happy punters getting access to the latest technology. But the world is full of competing interests, and they will all use the rules of the game to their advantage if they can.

Does this matter? The simple answer is yes. It's clear that modern economies rely on IT and communications, and that economic growth depends on innovation. That means the best possible broadband - whether fixed or mobile - at affordable prices as early as possible. 4G - real 4G - is coming.

We have slipped back compared to Asia, the US and many parts of Europe and we need to be in the vanguard. 4G is overdue in the UK. Let's get on with investing so we can start using real 4G and get the economy moving.

David Cleevely runs the Centre for Science and Policy at Cambridge and also founded telecoms consultancy Analysys and advises Ofcom on spectrum allocation

- Published10 September 2012

- Published23 May 2012

- Published10 September 2012

- Published1 May 2012