Russia internet blacklist law takes effect

- Published

The law is aimed at protecting children from harmful internet content

A law that aims to protect children from harmful internet content by allowing the government to take sites offline has taken effect in Russia.

The authorities are now able to blacklist and force offline certain websites without a trial.

The law was approved by both houses of parliament and signed by President Vladimir Putin in July.

Human rights groups have said the legislation might increase censorship in the country.

The law is the amendment to the current Act for Information.

The authorities say the goal is to protect minors from websites featuring sexual abuse of children, offering details about how to commit suicide, encouraging users to take drugs and sites that solicit children for pornography.

If the websites themselves cannot be shut down, internet service providers (ISPs) and web hosting companies can be forced to block access to the offending material.

The list of banned website will be managed by Roskomnadzor (Russia's Federal Service for Supervision in Telecommunications, Information Technology and Mass Communications). It is meant to be updated daily, but its contents are not available to the general public.

Critics have described it another attempt by President Vladimir Putin to exercise control over the population.

"Of course there are websites that should not be accessible to children, but I don't think it will be limited to that," Yuri Vdovin, vice-president of Citizens' Watch, a human rights organisation based in Saint-Petersburg, told the BBC.

"The government will start closing other sites - any democracy-oriented sites are at risk of being taken offline.

"It will be [an attack on] the freedom of speech on the internet."

Mr Vdovin said that to close a website, the government would simply have to say that its content was "harmful to children".

"But there are lots of harmful websites out there already, for example, fascist sites - and they could have easily been closed down by now - but no, [the government] doesn't care, there are no attempts to do so," he added.

A risk for websites?

Besides NGOs and human rights campaigners, websites including the Russian search engine giant Yandex, social media portal Mail.ru and the Russian-language version of Wikipedia have all protested against the law.

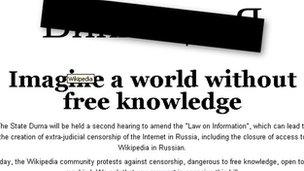

The Russian version of Wikipedia went dark for a day in protest at the law in July

The latter, for instance, took its content offline for a day ahead of the vote in July, claiming the law "could lead to the creation of extra-judicial censorship of the entire internet in Russia, including banning access to Wikipedia in the Russian language".

Yandex temporarily crossed out the word "everything" in its "everything will be found" logo.

"The way the new law will work depends on the enforcement practice," said a spokesman.

"Yandex, along with other key Russian market players, is ready to discuss with lawmakers the way it is going to work."

In July, the Russian social networking site Vkontakte posted messages on users' homepages warning that the law posed a risk to its future.

However, the country's telecom minister Nikolai Nikiforov, suggested that such concerns were overblown when he spoke at the NeForum blogging conference this week.

"Internet has always been a free territory," he said, according to a report by Russian news agency Tass, external.

"The government is not aimed at enforcing censorship there. LiveJournal, YouTube and Facebook showcase socially responsible companies.

"That means that they will be blocked only if they refuse to follow Russian laws, which is unlikely, in my opinion."

There is also evidence suggesting public support for the move.

A survey conducted by pollster Levada Centre, external in late July indicated that about 62% of those asked supported the idea of a blacklist, with only 16% opposing it.

- Published11 July 2012

- Published10 July 2012

- Published24 March 2011

- Published8 March 2012