Kickstarter: Games by the people, for the people

- Published

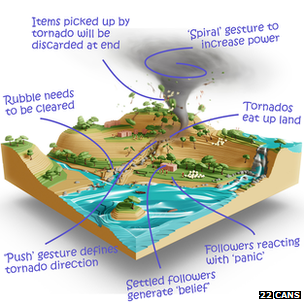

Project Godus lets players shape a world and the lives of its virtual inhabitants

Kickstarter has been good to video game fans in 2012. The crowd-funding site which lets people back projects they like has meant that lots of games that would otherwise never be made have found funds and friends via the site.

But good for gamers can be rough for gamemakers.

"By definition, Kickstarter is one of the most intensely scary experiences you can ever undertake," said Peter Molyneux, who used the site to raise cash for Project Godus, which aims to resurrect the god-game genre.

Godus sought to raise £450,000 in 30 days and initial interest was high, he said, but this tailed off a few days into the pitch despite developers posting almost daily updates. The slow trickle of funds led some to wonder if Godus would hit its target.

Sites such as Kicktraq cranked up the anxiety, said Mr Molyneux, by giving a snapshot of how many, or how few, pledged cash every day. For Godus, thousands signed up in the opening week but this fell to only a handful soon after.

"You start questioning your whole approach," he told the BBC. "The assets you are putting up, the design of the game - everything."

As an industry veteran Mr Molyneux had a Plan B to fall back on if Godus did not hit its target, namely taking it to an established game publisher. Why, then, did he use Kickstarter?

"The biggest reason is that if you want to make a great game, however you define that, is to involve your community in the making of it," he said. The close interaction between developers and players was much easier to do via Kickstarter than it would be via a publisher, he added.

Small start

For gamesmakers without the industry clout of a Molyneux, Kickstarter was useful for engaging a community of early fans.

Big Robot's tweedpunk robo-horror game was tricky to sell to established game publishers

"It's about getting feedback from players before it's even finished and getting players really excited about it throughout the process," said Jim Rossignol, co-founder of indie game studio Big Robot, which used Kickstarter to get funds to finish a game called Sir, You Are Being Hunted.

Perhaps more importantly for small game studios, he said, pledges helped developers manage their cashflow. Typically, he said, gamemakers spent all their money developing a game and had to hope it sold enough to recoup that outlay. Through Kickstarter, a big chunk of cash can arrive earlier.

In addition, he said, Big Robot turned to Kickstarter because the game, a "tweedpunk" horror title in which players are hunted by well-dressed robots in the British countryside, would be unlikely to win over a mainstream publisher.

There was no doubt, he said, that Kickstarter and other crowd-funding sites such as Indiegogo had kicked off a revival of the small gaming studio.

"There's greater diversity right now than we've seen for a while," he said. "A few gamemakers I've spoken to have said that a few years ago this kind of development was dead. They would have to go and make console games for big studios instead."

Community chance

But Kickstarter is not the only way that gamemakers can find and engage with fans. In early 2012, Slightly Mad Studios, which has a string of PC and console hits to its name, kicked off its World of Mass Development (WMD) programme.

This operated like Kickstarter in that fans could hand over different amounts of cash to buy different levels of involvement in a racing game called Project Cars. The lowest level of involvement, which costs £10, lets players comment on discussion threads and play monthly builds of the game. Higher levels, which cost £10,000 and above, let players attend company meetings, put them in personal contact with developers and let them plays all test versions of the game.

For their cash, WMD participants will get a cut of the returns Project Cars makes when it goes on sale.

Andy Tudor, creative director at Slightly Mad, said WMD was about taking gaming to the people.

Project Cars is a crowd-funded and developed racing game

"We don't think that people get enough value for their money from games," he said. "We want to take them behind the scenes and show how games are made."

Mr Tudor said the early days of WMD were rough as the studio struggled to cope with the opinions expressed by the tens of thousands who signed up - far more than expected. Now, he said, the process was much smoother and work was proceeding well for a launch in 2013.

WMD also put Slightly Mad in charge of its own destiny as it will own all the assets produced in the game. By contrast, he said, when it worked for a publisher that intellectual property was handed back when the game was done.

For Mr Tudor, WMD signals the end of the "fire and forget" days when studios produced games and had nothing more to do with them when they hit the shop shelves and it has plans to use it for future titles.

One big question remains over this fan involvement.

"The jury is still out on whether crowd-funding produces really good, high-quality games," said Mr Molyneux. "In 2013 we need to see a few successes and have crowd-funded titles beating published games in the charts."

- Published22 November 2012

- Published19 October 2012

- Published6 November 2012

- Published12 October 2012