How hardware hacking (almost) made me a fraudster

- Published

Swapping out a faulty motherboard led to a whole heap of problems

I was in a hurry, in a queue and had 12 minutes to buy a ticket and run to the platform to catch a train to Cambridge.

At the ticket machine, I slid in my debit card, punched up the route and chose a day return. I hit confirm and the machine thought about it. Thought some more. And more.

A message popped up. "Card declined." Nightmare.

But... no money? Really? I was sure the Wards were solvent. I had to check even though the train left in, oof, six minutes. I put the declined card in a cash machine wondering if I'd get it back. It wasn't eaten and the Wards were flush with cash.

So, what was happening? On the train I racked my brain trying to work out why the card had been declined. My mobile rang, I answered, distracted, then sat up straight. "This is a fraud warning..." said an automated voice. It talked me through six transactions put on hold because they were suspected of being fraudulent.

I had made all of those purchases. They were all legit. What was going on?

Could it be a virus? How embarrassing would that be for someone who regularly writes about computer security.

A clue came from the first transaction flagged as potentially fraudulent. What had I done on that day? . Really? Could that be it? On that day my son Callum and I engaged in some father-son bonding by swapping the faulty motherboard on the family PC - the motherboard is the bit into which you plug all the other parts of a PC - processor, graphics card, memory et cetera. Cal and I high-fived when it booted the first time we turned on the power. A good day.

Was that it? Had a bout of harmless home hardware hackery led to me being flagged as a fraudster?

Looking deep

It might, said Akif Khan, an anti-fraud expert at security firm CyberSource. The reason could be the security measures that many websites use to combat fraud. Often, he said, they built up a "device fingerprint" of the machines used to visit.

These fingerprints look deep into the characteristics of the machine, logging such things as the time zone, keyboard language, operating-system version and other key identifiers.

Using the same machine over and over built up a trusted-relationship status with online retailers, he said. That status could have been revoked or lost when the motherboard was swapped.

I keep my computer locked down pretty tight but had I fallen victim to a virus?

"A family PC, probably with various users and credit cards, may well have triggered velocity rules and raised the risk of those transactions, which were suddenly all appearing to come from a new previously unseen device," he said.

Those "velocity rules" are all about how many transactions are made within a given amount of time. Criminals who steal credit cards often go on a spending spree to maximise the return they get before a card is stopped. On the day I'd swapped the motherboard, I'd made quite a few purchases online unwittingly mimicking those eager cyber-thieves.

"Unfortunately scenarios such as this may result in retailers rejecting genuine orders due to suspicion of fraud," said Mr Khan. Deciding whether something is fraudulent or not was a question of weighing up probabilities, he said. Fixing the PC had put me on the wrong side of that sum.

While swapping the motherboard is like re-building the foundations in your house, my thinking was that because the same house would be built on a different substructure, no-one would notice.

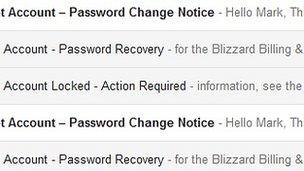

It turned out that lots of people did. When I got home my wailing children told me we'd been locked out of lots of game accounts and I had to field a series of emails telling us to re-set passwords. When I booted up the computer to sort these, Windows told me to re-validate my copy of the operating system. Fabulous.

The motherboard swap was undoubtedly the cause of all the trouble, said James Gorbold, a veteran DIY PC maker from electronics firm Scan, which sells computers and components.

"What I suspect has happened is that your motherboard will have a different network controller," he told me.

That was important, he said, because by swapping that component I triggered a cascade of other changes that made it look like a different machine.

The change meant we were locked out of lots of online games

Information about the underlying make-up of the PC could well have been communicated somewhere along the line to my ISP or to the websites I've regularly used. That information, coupled with the IP address gives a basic guarantee of ID. Changing them may have made it again look like I was a fraudster because some of the information was the same but other key measures had changed.

Turning everything off, including my router, to do the swap might also have meant I got a new IP addresses again making it look odd.

In addition, said Mr Gorbold, Windows XP uses a points-based scheme to work out if users need to buy a new licence for the software.

Swapping the motherboard might well have tipped me over the points limit, leading Windows to report that I was effectively running a new PC. Again, to those without all the facts, I looked dodgy.

This has been a sobering experience. Good because I found out quickly about potential abuse of my credit and debit cards. Bad because of all the running around I had to do to fix the problems it caused. It's not put me off tinkering with the family hardware, though I might not mention that to my wife, just yet.

This article has been updated to more accurately reflect Mr Gorbold's comments as we mistakenly said that MAC addresses are passed to ISPs.

- Published26 April 2012

- Published19 January 2013

- Published27 September 2012

- Published15 November 2012