Bitcoin: Dawn of a new currency or destined to fail?

- Published

Bitcoin activist Amir Taaki believes the innovation will prove to be a force for good

Who would have thought one of the tech wizards behind a global currency would live in a squat?

Amir Taaki is a developer who works with a virtual currency called Bitcoin. His home and office is an abandoned Buddhist temple. The dwelling is covered in brightly painted but slowly decaying murals of Buddha, with the odd makeshift bunk bed and flotsam furniture like a couch with no pillows.

His fellow squatters are members of the Occupy movement and Mr Taaki's Bitcoin philosophy is very much in line with theirs.

"Bitcoin is for pure financial freedom of speech," he says. "It really changes the dynamics of how money works."

His voice exudes passion for the currency.

"Bitcoin is the proper perfect economy," he says. "The technology needed to participate is open, the entry and exit is basically very cheap or free, there's no barriers to competing in that network."

The currency exists exclusively online and is independent of any government or company.

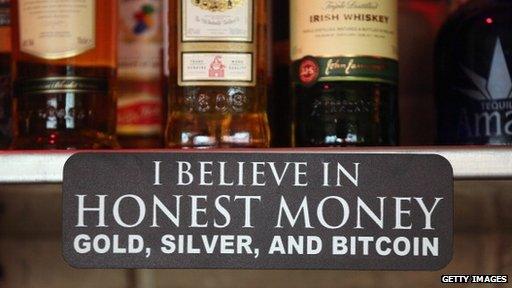

It was spawned in 2009 by an unknown person or group of people calling themselves Satoshi Nakamoto. Early adopters, including Mr Taaki, were mostly tech-minded people with distrust in regulated banking institutions.

Like other currencies it is used to buy goods and services. Companies selling anything from software, pizza and online dating are jumping on board - accepting it as payment.

But what makes Bitcoin attractive to many of its users is its relative anonymity.

"You can make as many Bitcoin addresses as you want," Mr Taaki says.

"So that's how you preserve your anonymity because you give every person a different Bitcoin address so they don't know what Bitcoins are connected to you."

Because Bitcoins are hard to regulate and transactions tough to trace, the currency is a haven for black market activity spearheaded by an online marketplace for illegal drugs and fake IDs called Silk Road.

A Berlin-based bar is among a growing number of businesses to accept Bitcoins

Silk Road accepts Bitcoins as payment. "It's a really powerful thing," says Mr Taaki.

The activist says Bitcoin's use on Silk Road has been a good thing for libertarian reasons - but adds that there is also potential for less controversial uses of the currency which are not easily supported by the current banking system.

"You can make distributed, publicly funded services using Bitcoin, you can have micro-philanthropy," he exclaims.

"A lot of people think our financial problems should be solved by laying on more regulation but the thing with that regulation is it enforces monopoly. It puts more power into the guys who can comply with that regulation."

"It closes out the idealistic guys at the bottom who actually want to change things."

The currency's links to illegal activity have not deterred people from becoming interested in it.

Demand has recently been bolstered by distrust in traditional financial institutions stoked by the banking crisis in Cyprus.

This, along with speculative investors, caused the value of a Bitcoin unit to double in a matter of weeks. It has since become more volatile, experiencing a drop of over half of its value in one day.

According to data from Bitcoin Charts, external, the past week alone has seen the value of one Bitcoin range from $266 (£172) to $50 (£32).

Users' Bitcoin savings can be stolen if they fail to protect the encryption keys in their Bitcoin wallet

Bitcoin saw a similar boom in 2011 followed by a crash. Its unpredictable nature has incited a fear of history repeating itself but Chris Cook, a senior fellow at University College London's Institute for Security and Resilience Studies says the volatile nature of the currency is just a symptom of changing supply and demand.

"At the moment it's increasing rapidly because there's a massive interest in it," he says.

"Once that demand ceases it may stabilise. On the other hand other people may come in and say 'oh I made a lot of money on my Bitcoins, I might sell some,' - in which case we would see the price come down."

But the Bitcoin system isn't airtight. There have been a number of Bitcoin thefts by hackers and even a Ponzi scheme cheating investors out of millions of dollars. Mr Cook says that's just the cost of doing business.

"Bitcoin is disruptive, it's changing the game completely, but it is fundamentally flawed," he says.

"If you get hold of a code, a Bitcoin code, then it's yours. As far as that goes, whoever had it has lost it. It's like a bare instrument, it's like a coin."

Mr Cook adds that it's an attractive outlet for virtual crime.

"The more expensive it gets the more you'll find that all the world's online criminals focus and descend upon the people who have access to Bitcoins."

This hasn't stopped Bitcoin's users from believing and investing in the currency.

Jeff Berwick is one such entrepreneur. He has developed the first Bitcoin cash machine, which will convert a person's Bitcoins into the currency of the country where they are withdrawn.

"Over 200 people have said they're interested in buying a machine or more than one from 30 different countries," he says.

He says he plans to put one of his first machines in Cyprus where the amount of money people can take out of machines is restricted because of strict financial regulations.

"This is a way to transact outside of the traditional, regulatory monetary system," he says.

However, optimistic Bitcoin supporters are, the future of the currency is hazy and unpredictable.

But Mr Cook says he believes the importance of Bitcoin does not revolve around the currency itself, but rather the concept of alternative currencies and their place in the global economy.

"It's a sign of the way that things are going to go," he says.

"Networked currency and networked transactions are going to look very different from the banking system that we know."

- Published15 April 2013

- Published12 April 2013

- Published11 April 2013