Tomorrow's cities: Rio de Janeiro's bid to become a smart city

- Published

Rio: Latin America's first 'smart city'?

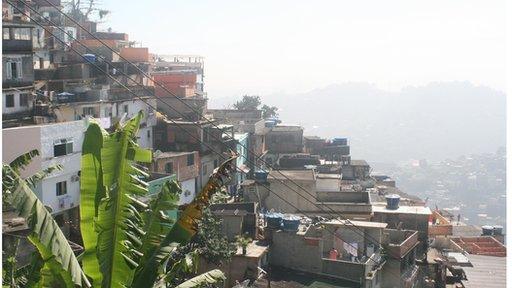

Rio de Janeiro's famously chaotic favelas are as much a landmark of the city as the Christ statue or Sugarloaf Mountain but few would see them as the natural home to smart technologies.

However, a remarkable project is under way that is already changing lives, and it is one of which the city government, keen to put Rio on the map as Latin America's first smart city, should take note.

Morro dos Prazeres favela is one of the areas that has been mapped by teenagers

The project, co-ordinated by Unicef in collaboration with local non-government organisation CEDAPS (Centro de Promocao da Saude) has local teenagers digitally mapping five favelas in order to highlight some of the challenges for those living there.

Teenagers take aerial shots of their neighbourhood using digital cameras sitting in old bottles which are launched via kites - a common toy for children living in the favelas.

They then use GPS-enabled smartphones to take pictures of specific danger points - such as rubbish heaps, which can become a breeding ground for mosquitoes carrying dengue fever.

The data is uploaded to a website, external and added to an online map.

It is proving an effective way of getting changes made.

A nursery school that once balanced precariously near the edge of a sheer drop now has a balcony, many of the steepest steps in the favela have had railings fitted and recycling bins dot the area to discourage residents from stockpiling rubbish.

The teenagers launch kites fitted with digital cameras to take aerial shots of the favela

Ives Rocha, who managed the project, thinks it is a fantastic example of what smart cities should really be about.

He has been invited to discuss the project at the mayor's office and hopes that the map can be included on a hi-tech one that sits in the city's operations centre.

The operations centre is the heart of Rio's bid to become a smart city.

Opened by Mayor Eduardo Paes in 2010, it is, like the favela project, using cameras to better understand the city.

It boasts an 80m wall on which are streamed video feeds from 900 cameras around the city.

A plasma screen shows a Google Earth view of the city while a satellite map feeds in weather data that is connected directly to sirens in the favelas that will alert inhabitants when flooding is predicted.

Fifty operators from 30 different city agencies - all dressed in matching white boiler suits - monitor the city in real-time.

They can act quickly if disaster strikes, diverting traffic if an accident occurs, alerting the correct people if a sewer pipe bursts or set off the sirens if heavy flooding threatens. The media sit in a room above the operation centre to react quickly if something happens.

The uniform is intended to make people from hitherto separate agencies feel that they are part of one city, explained Pedro Junqueira, chief executive of the centre.

Coupled with the banks of computers and big screens, it also makes them look like they are engaged in a Nasa-style project

But Mr Junqueira admits that currently the centre is using only about 15% of its processing power.

How smart?

Rio's operations centre co-ordinates city services - but how smart is it?

It has led some to question how smart the centre really is.

"I wonder whether it is more a showcase for the mayor to show that the city is prepared for the World Cup and the Olympics. It looks impressive to have a mission control, Nasa-style, but all that is coming into it, from what I can tell, is video feeds," said Anthony Townsend, director of the US Institute of the Future and author of Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for A New Utopia.

"IBM's weather modelling system is fairly novel but the rest is just a lot of spin."

Mr Junqueira admits that the centre is only just beginning to get smart and that the next stage will be to "build a new room" where analysts will start crunching the data.

"For now it is more about monitoring and reacting as fast as possible and trying to find some correlations, so if something happens, what happens after it?" he said.

Already the data has revealed some interesting statistics, such as the fact that the majority of motorcycle accidents in the city happen between 17:00 and 19:00 on Fridays.

Having that information could lead directly to policy change, said Mr Junqueira.

"Maybe we will say that, on Friday afternoons motorcycles can't go in particular streets, for example."

Camera view

The cameras that feed into the operations centre also showed images of the protests online

Rio hit the headlines earlier this summer when protesters took to the streets to voice their concerns about a range of issues, from how much was being spent on the stadiums that will showcase the forthcoming World Cup and Olympics to the price of bus fares.

Such unrest was a long way from the mayor's vision of a smart city but ironically the camera feeds from the operation centre - which are also available to view online - soared in popularity.

"During the demos many people wanted to see how they were going and they went to look at the camera views and there were no images - it seemed as if the cameras in those areas where the protesters were had been turned off," said author and blogger Julia Michaels, who has lived in Rio for the past 20 years.

Mr Junqueira is quick to deny that the cameras were switched off, saying that the system was simply unable to cope with demand.

"Some people thought that they were shut down but when everyone wanted to look at the same picture there were some technical difficulties. Cameras went down but this was only for a short time," he said.

But for Ms Michaels the fact that the cameras didn't work when citizens needed them represents a disconnect between what the government is trying to achieve and what citizens actually want.

"It is emblematic of what it is like to install a hi-tech system in a place where there is still so much else to do," she said.

School campaign

The operations centre is attempting to engage citizens.

It has just formed a partnership with Waze, a community-based traffic app that collates real-time traffic information. It was first used during the Pope's visit and was extremely successful in alerting people to which roads were closed, said Mr Juanquira.

And next month the centre will host its first hackathon.

But there remains a vast gap between the government and the citizens, thinks Miguel Lago.

He is one of the founders of Meu Rio, a technology platform that offers ordinary people an interactive platform to campaign about the issues that matter to them.

One of its recent successes has been to prevent the demolition of a school that sits within the world-famous Maracana football stadium complex.

"The government wanted to knock it down as part of its World Cup and Olympic plans, either to make a parking lot or possibly a training ground for athletes," said Mr Lago.

"The parents were given no warning and so one of them decided to use our platform to campaign against it."

Taking inspiration from the city-wide cameras that feed information into the operations centre, the group decided to set up their own camera to monitor the school.

People were invited to become guardians and watch the webcam images online 24 hours a day, alerting everyone involved via text message if a demolition team began work.

The campaign attracted 20,000 followers, garnered a lot of press coverage and recently heard that, for now at least, the school is safe.

It is a reminder that smart technologies need to work both ways.

"These tools can be used to control citizens but we need also to use them to allow citizens to control government," said Mr Lago.

Commonsense urbanisation

As Rio carves its own path to smartness, other Latin American countries are taking a different, less technology-led approach.

Ex-Mayor of Bogota Enrique Penalosa is now a regular speaker at smart city conferences around the world, arguing that the first priority for cities looking to future-proof themselves is to deal with the traffic that blights them.

At one event he envisioned a new American city with thousands of miles of greenways and pedestrian walkways.

"Cities are only a means to a way a life and whatever we do over the next 40 years will determine the quality of life for millions. I am convinced that we need radically new designs... that can lead us to more sustainable cities where people will lead much happier lives," he said.

Urbanist and architect Teddy Cruz thinks that Rio would do well to look at how Colombia has transformed its cities.

"This wasn't about the new, it was about altering and adapting - common-sense urbanisation," he said.

"It isn't all about sexy buildings or symbols of progress. In reality Rio could be losing its sense of true intelligence which is already embedded in the city."

- Published19 August 2013

- Published27 August 2013